In the nine years since publishing his first book, Thoughts Without a Thinker, Mark Epstein, M.D. has done more to pioneer the meeting of Buddhist and Western psychologies than any doctor in this country. Now turning this cross-cultural gift to the polarizing topic of Eros, Epstein continues to break new ground in his forthcoming book, Open to Desire, envisioning a middle path where lust for life-questioned in some dharma circles-is no longer seen as the enemy.

Trained at Harvard, Epstein, whose other books include Going to Pieces Without Falling Apart and Going On Being, is a longtime meditator who lives in New York City with his wife of twenty years, Arlene Schechet, and their two teenage children. One chilly afternoon last fall, attired in a black T-shirt and khakis, he met with me in his basement office to talk about this thorny issue of desire.

—Mark Matousek

You are working on a book about desire. Why desire? After studying Buddhism for thirty years, I realized that people have this idea that Buddhism is about getting rid of desire. I don’t think that’s true, so the book is a defense of desire, really—an exploration of the Middle Way, trying to chart out an approach to desire that isn’t about indulging, necessarily, or repressing.

Why does desire need defending? From the Western, Puritan point of view, it’s always been seen as dangerous, devilish, the enemy. From the Eastern spiritual point of view—as adopted by many Western practitioners, at least—it has the connotation of something to be avoided, a poison. As a psychotherapist, I’ve been trained not to avoid the so-called “real stuff’—anger, fear, anxiety—and this certainly includes desire. Desire is the juice. It’s how we discover who we are, what makes a person themselves. I wanted to try to explore how to work with it more creatively.

Many of the ancient stories of the Indian subcontinent, like the Ramayana, the epic tale of separation and reunification of the lovers Sita and Rama, explore desire in an expansive, imaginative way. In the Ramayana, Sita is kidnapped by the demon Ravana and separated from her lover, Rama. Ravana wants to possess Sita totally. He is enthralled by her but can only see her as an object. Sita resists this, and in her isolation and imprisonment she deepens her own desire for Rama. The separation that Ravana brings about helps her to get more in touch with the nature of her own desire. I was intrigued by the way desire and separation are intertwined in the tale, as if you can’t have one without the other. There seems to be a teaching there about what constitutes a true union. I’ve been reading over these stories to try to bring back some of this ancient wisdom.

We should probably define our terms. Are we talking about sexual desire? Carnal desire? I’m taking the psychodynamic view that all desire is really sexual at some level. Freud once said that he wanted to show that not only was everything spirit, but it was also instinct. One of the wonderful things about the Indian perspective is that it doesn’t make the same distinctions between lower and higher that we are used to. Lower and higher are one. There is a much more unified view, so that there is no question but that the sensual contains within it the seeds of the divine. The view in the West, at best, is that things are organized in a hierarchical way, with sensual pleasure being a lower rung on a ladder that reaches coward the sublime. In the Indian view, it’s not a rung, it’s the entire ladder. So I’m trying co keep a focus on sexual desire throughout.

With the same general implications of clinging and attachment? The question is whether clinging and attachment are an intrinsic part of desire. Sometimes in Buddhist scripture they really seem to be talking about desire in a more celebratory way. When I make my defense, I like to make that distinction. The Buddha warned against the clinging and craving that arise when we try to make the object of desire more of an “object” than it really is. If we stay with our desire, however, instead of rejecting it, it takes us to the recognition that what we really want is for the object to be more satisfying than it ever can be.

The Buddha’s teachings emphasize that because the object is always unsatisfying to some degree, it is our insistence on its being otherwise that causes suffering. Not that desiring is negative in itself. We can learn to linger in the space between desire and its satisfaction, explore that space a bit more. In my interpretation, this is the space that Sita was in during her separation from Rama. When we spend more time there, desire can emerge as something other than clinging.

Or addiction? Yes. Desire becomes addiction after you have that first little taste of something—alcohol, great sex, getting stoned—that comes so close to complete satisfaction…then you start chasing it. The same thing happens in meditation: having that first bit of bliss, then it’s gone. You want the perfection back. But you’re chasing something you’ve already lost. If you stay with that widening dissatisfaction and think, “Oh, yeah, of course,” then insight can begin to happen. In that gap.

So our relationship to desire is the problem. That’s the point I’m trying to make. Different teachers have different approaches to this: some recommend avoidance of temptation or renunciation, while others talk about meeting desire with compassion. Another strategy is to recognize the impermanence of the object of desire for instance, by countering lust with images of how disgusting the body really is.

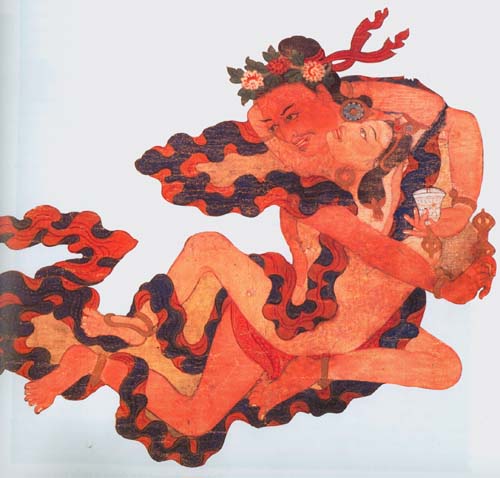

Other teachers say that desire is really just energy that we have to learn how to use without getting caught by it. This is traditionally found under the rubric of Tantra, but it appears throughout the Buddhist canon. There’s the famous Zen story in which the Buddha holds up a flower, and only one disciple grasps his meaning and smiles. There are many interpretations of this story, and mine is perhaps unorthodox. But the flower, in Indian mythology, seems to be the symbol of desire. Mara, the tempter, shoots arrows of desire at the Buddha, and the Buddha turns them into a rain of flowers. Kama, the god of Eros, shoots five flowered arrows from his bow. When the Buddha holds up the flower, he might be saying, “No big deal.” Desire is something that can be met with a smile.

As a therapist, do you believe that it’s possible to reject desire in a healthy way? Of course. There’s something very useful about the capacity for renunciation. I think that renunciation actually deepens desire. That’s one of its main purposes. By renouncing clinging, or addiction, we deepen desire.

Think of Shiva. In the Indian myths, Shiva is the great meditator, the supreme renunciant. He was so absorbed in his meditation that the gods once tried to rouse him to come to their aid in a battle by sending Kama to wake him. But Shiva reduced Kama to ashes with one glance from his third eye. He was so powerful, he could incinerate desire with one look. But the world could not survive without Eros. The gods pleaded with Shiva, and he resurrected Kama as easily as he had destroyed him. He then left his meditative absorption and turned toward his lover, Parvati. They had sex for the next thousand years. The bliss of their lovemaking was the same as the bliss of his solitary meditation. This is the essential teaching of Shiva: thattapas, the heat of renunciation, is the same as kama, the heat of passion. One deepens the other. The Buddha’s point, I think, was that by renouncing clinging we actually deepen desire. Clinging keeps desire in a frozen, or fixated, state. When we renounce efforts to control or possess that which we desire, we free desire itself.

So it’s selective renunciation. I think so. Because you don’t want to snuff out the love. They say that the Buddha taught each of his disciples differently. He could look at each of us and see where the clinging was.

It may not be so much that we have desire as that we are desire. Trying to renounce desire is like trying to renounce yourself. This isn’t the way to see the emptiness inside. But clinging is different. We can renounce clinging without estranging ourselves from desire.

Selective renunciation deepens desire because you separate out what’s addictive. You free up the erotic? The question would be, What is the truly erotic?

Enlighten us. I think it has something to do with playing with separateness: trying to erase it while at the same time knowing that we cannot. There is a tension between the control we wish we had and the freedom that is naturally present. There were great religious debates in seventeenth-century India about which would bring you closer to divine desire: being in a committed relationship or having an adulterous one. And the adulterous relationship won out because of the quality of separateness, of otherness, that the illicit relationship had. The relationship between husband and wife in those days was more about property. The woman was completely objectified; everything was scripted. There was no room in that relationship for the quality of hiddenness that makes something erotic—or of teasing.

In Japanese garden design there is a principle called “Hide and Reveal.” They make a path near a waterfall so that you can never see the waterfall entirely from anyone vantage point. You can only get glimpses of it—there’s something in that that relates to the erotic. In psychodynamic language, this is the ability to have a relationship between two subjects, instead of a subject and an object. Can you give your lover the freedom of their subjectivity and otherness? Admit that they are outside of your control?

Which in turn could help us remain unattached… Any attempt to attach too much will only lead to frustration and disappointment. But attachment is a tendency that is endemic to our minds. We can’t just pretend it’s not there, but if you can keep coming back to the truth—that what we desire is not ours in that sense—we can confront our own grasping nature, which, if seen clearly, self-liberates.

What are some of the practices, skills, that someone caught on the merry-go-round of desire can use to find the Middle Way? Meditation is the basic tool for that. In training the mind in bare attention, not holding on to pleasurable experiences and not pushing away unpleasant ones, we can learn to stay more in touch with ourselves. When we practice in this way, pretty quickly we can find out where we are stuck. The mind keeps coming around to the same basic themes. One of my first Buddhist teachers, Jack Kornfield, writes very movingly in his book A Path with Heart about his early experiences in long-term meditation at a monastery in Thailand. His mind was just filled with lust. He was freaking out about it, but his teacher just told him to note it. Despairing that it would never change, he tried his best to follow his teacher’s instructions. And what he found was that, after a long period of time, his lust turned to loneliness. And it was a familiar loneliness, one that he recognized from childhood and that spoke of his feeling of not being good enough, not deserving enough of his parents’ love. I think he said something like, “There’s something wrong with me, and I will never be loved.” Something like that. But his teacher told him to stay with those feelings, too; just to note them. The point wasn’t to recover the childhood pain, it was to go through it. And eventually the loneliness turned into empty space. While it didn’t go away permanently, Jack’s insight into something beyond the unmet needs of childhood was crucial. This is one way to unhook ourselves from repetitive, destructive, addictive desire. It lets us go in a new direction—it frees desire up.

The way we try to extort love or affection from people can be very subtle. Or we may use food or drugs or television or whatever else to try to get that extra something. When we don’t get it, we wonder what’s wrong with tis. And the layers of addiction are never-ending. An alcoholic can stop drinking, but that doesn’t mean he’s not using sex to the same end, you understand. These layers extend all the way down to someone in a monastery, who can still be addicted to some pleasant feeling in meditation. In Buddhism they say that the most difficult addiction to break is the one to self.

The other tendency in meditation is to push away what we don’t want, but aversion constitutes self as much as desire. This can lead to the anti-erotic, anti-celebratory, anti-emotional tendency among some Buddhists. This keeps them feeling more cut off than they want to be.

In a culture of addiction—with overavailability of nearly everything—isn’t the learning curve especially steep when it comes to confronting desire? One thing that has helped me think about this is the psychoanalyst Jessica Benjamin’s theory that there are two kinds of desire. A male desire (present in both sexes), which knows what it wants and is going after it, which is all about trying to obtain satisfaction. And a female desire, not just in women, which is more about interpersonal, and intrapersonal, space. The male desire is about doing and being done to, while the feminine desire is about being. Think of a baby at the breast. In one version, the breast is trying to feed the baby—it’s forcing itself into the baby’s consciousness, or the baby’s mouth. In the other version, the breast just is. The baby has to find it, discover it, for herself. It’s almost like our culture is hip to “male” desire, assaulting us constantly with “you want this, you want that.” It’s so much in the object mode that it doesn’t yield the room for what she’s calling a feminine desire, which is “Give me some space to know what I really want.”

What do you think about transcendence of bodily desire as a healthy path?Transitionally, it might be valuable for people at certain times. So much of our conditioned experience is spent in the lower part of our body. And it’s certainly helpful for the sick body. You want to know that your mind is more powerful than any of that, that you’re not only that but exist psychically, emotionally—on many levels all at once. I remember when I would take classes with Ram Dass, and he would only teach from the heart up. He would lead guided meditations where the energy would only circulate from the fourth through the seventh chakras. It was always implicit, though, that we would bring the energy back down to the lower chakras eventually.

But transcendence as the ultimate thing, I haven’t found that to be helpful. It seems like the only idea that really makes sense to me is this one: samsara and nirvana are one. Dissociating yourself from any aspect of who you really are is only a setup for future trouble. The ultimate thing has to be a complete integration of all aspects of the self.

In your own evolution as a lover and practitioner, has your relationship to desire chanqed, hit walls—have there been tangles? Not to get too intimate… It’s always been a question for me. When I first started to practice, I was mostly aware of my anxiety. But as my mind started to calm down, I began to notice my own desire more. As if desire and anxiety are two sides of the same coin. I’ve always had a basic view, I suppose, that the Middle Path was the only way to go. Getting to know my first meditation teachers helped. I remember after one of my first Vipassana retreats with Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield, I went into town with them to eat in a restaurant. I think they must have ordered meat or something—they had no pretension about them. It was such a relief. I didn’t need to idealize them; their humanness was very obvious and very touching. For me it meant that I didn’t have to try to be something other than what I was.

That’s one of the main things that encouraged me to become a therapist—the relief I felt at not trying to be other than I was. Suzuki Roshi used to talk about using the manure of the mind as the fertilization for enlightenment. That’s how I felt about accepting who I was. I understood that I had to make use of whatever I actually was—not pushing it away was as important as not holding on to it.

I’m interested in this question of transformation. Can laypeople actually transform desire? How much of this is imagination? Tantra is all about the capacity to imagine. Once you understand the emptiness of phenomena, you have the freedom to imagine another reality—superimpose another reality on this one. It’s just as real as this one, which you’ve already understood is empty.

So the energy isn’t actually changing? The energy isn’t actually changing, no.

“Transformation” is a misnomer, then. Is imagination as important in connecting sex and love, do you think? I think sexual desire is the physical attempt to reach the other, coupled with the intuition that they are forever out of reach. A famous psychoanalyst named Otto Kernberg speaks of sexual union as the experience of a lover revealing himself or herself as a body that can be penetrated and a mind that is impenetrable. You feel these two things simultaneously. Sexual desire has both the male and the female element: the attempt to possess or take over the other, coupled with the impossibility of ever really grasping them. And it’s out of that combination that love, empathy, compassion—all those other feelings—emerge. Through realizing the lover’s otherness.

That’s the basis of love? I don’t think that’s the basis of love, but that’s what happens when you’re in love. Being able to appreciate, feel compelled by, the infinite unknowability of the other. It’s a mystery you want to get closer to, where there’s a yielding but not an ultimate merger. Both of you remain free.

Sex is a real vehicle for experiencing this. Which is why, in Tibetan Tantra, they use sexual relation as a metaphor for what is realizable through advanced practices. Sexual relation is as close as one can come in worldly life to experiencing the mingling of bliss and emptiness that is also understandable through solitary meditation practice.

Yet sex and mindfulness are not necessarily great bedfellows. Lots of us use, or have used, sex as a great way to get unconscious. Yet even with the senses overwhelming us, there’s still some awareness there. And it may be that very sort of awareness, of mind at the brink of going under, that’s most powerful. The moment of orgasm is classically seen as a doorway to higher consciousness, but most of us don’t stay there for very long. In fact, we run away from it, a little bit afraid of how overwhelming it is. As I understand it, Tantra is about staying within that doorway longer, to rest in the bliss. That’s what you train yourself to do. The nonconceptual bliss that you can only really taste through intimate sex, or spiritual practice.

Which is obviously very easy to become addicted to. Yes.

How does pleasure differ from joy, do you think? Buddhist psychology says that every moment of consciousness has pleasurable, unpleasurable, and neutral qualities. Even after enlightenment, these feelings persist. They don’t go away. But joy—the Pali word issukkha, the opposite of dukkha, or unsatisfactoriness—is a fruit of realization. The capacity for joy increases as the attachment to the self diminishes. In the end, everything becomes sukkha. You know, even dukkha becomes sukkha. So I think it all becomes pleasure.

Yet pleasure has such a bad rep in the Buddhist world. And that’s unfortunate. Because the Buddha taught not only abour suffering, but about the end of suffering. Desire is only a problem when we mistake what’s ephemeral for an object, something we can permanently grasp. It’s only suffering because we don’t understand. You know, this knowledge is encoded in the great Buddhist monuments, or stupas, that were built at the height of Buddhism’s flowering in India. Surrounding the central mound of the stupa—where the ashes or bones of the Buddha or another enlightened being were stored—was a processional area where visitors to the stupa could circumambulate in a kind of devotional walking meditation. Bur enclosing the processional area was a great circular railing carved with all kinds of sculptures. These sculptures were often of all of the pleasures of worldly life, and they often included erotic scenes, couples in all forms of embrace, goddesses with trees growing out of their vaginas, these kinds of things. And you had to pass through these scenes, or under them, to reach the processional area. The pleasures of worldly life were the gateways, or portals, to the Buddha’s understanding, as symbolized by the central mound. They are blessings that lead us further toward the Buddha’s joy.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.