If you sit long enough, your cushion will become an island amid a sea of dust. Thistles will overtake the yard. Things will begin to fall apart. At some point, you’ve got to clean house. The idea of ritual chores is intriguing to some, but for many of us, housekeeping has become work as rut. The thought of picking up a mop or a scrub brush is met with apprehension. This is where work-practice comes in: with the right approach, these daily chores can be done ably, even artfully. As with sitting, the important thing is to begin.

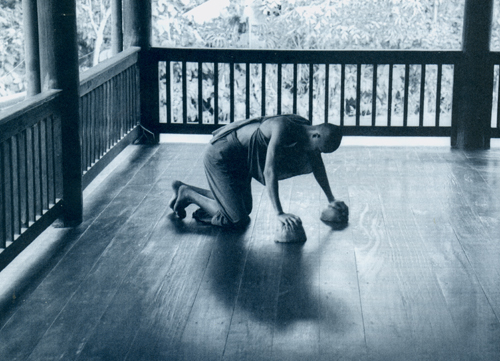

By some accounts, it was routine house and yard work that saved Zen Buddhism from almost certain oblivion. In the eighth and ninth centuries, Chinese Buddhist temples filled with monks who sought escape from military conscription, family problems, tax collectors, and indentured servitude. Sitting on a cushion and occasionally reading a Buddhist text were vastly preferable alternatives to the realities of outside life. As the story goes, it was Ch’an master Pai Chang who single-handedly came to the rescue. With his “no work, no food” edict, he immersed monks and teachers alike in the busyness of growing vegetables and performing routine temple maintenance. In this way, he revitalized life in the temple community and energized Zen practice. The temples bustled with daily activity, and any slackers were asked to leave. The energy created during communal work periods had a direct, dynamic effect on the monks’ zazen practice and honed the teachers’ skills. Even the quiet periods of the day were imbued with renewed meaning.

There is nothing more practical than learning how to care for the place in which you live.

In practice centers today, when we sweep cobwebs from the rafters of the meditation hall or wipe spilled water from the kitchen sink, we are experiencing a vital, direct, and immediate connection to Pai Chang and all the teachers who followed him. With a stubborn but kindly persistence, our predecessors eventually reach every corner of our lives.

I once lived in an apartment so small I had to step outside into the adjacent hallway to open my oven door. There was room only for a bed, a radio, and a cardboard carton of books. I kept my clothes in a closet down the hall. Even in this confined space, there was housework to be done. Indeed, the demands of maintenance follow us wherever we find ourselves, from palaces to prison cells.

The Italian poet Cesare Pavese wrote in his journal that we never remember days, we remember only moments. And Zen teachers tell us that this moment is the only one we’ll ever have. Perhaps this is a better way of looking at enlightenment. It’s not achieving or gathering something. Nor is it losing or overcoming something else. It’s simply stepping outside of the room you’re in and allowing the oven door to open. It’s checking the ceiling overhead and cleaning up the spills beneath your feet.

The best tool is often the one nearest to your hand, and cleaning the place where you live can be intimate and immediate. When Pai Chang demolished the traditional hierarchies within his temple, encouraged daily activity, and chastised the lackadaisical behavior of his monks, he was after more than just a clean house. He sought a method of practice that could utilize both meditation and activity inside a daily setting. Even now there is nothing more practical than learning how to care for the place in which you live. Maintaining your home can create a radical and radiating effect; however, you should not be misled. You are not a dark-robed Cinderella who must scour pots, carry out the ashes from the wood stove, and peel root vegetables in order to experience love, truth, and beauty forever after. The truth of the matter awaits you in the very acts of scouring, carrying, and peeling. With practice, there is a critical point where resentment toward your work lightens, where you begin to settle into yourself.

Zen is sometimes best defined by what occurs around its edges. In a formal setting we can observe Zen students sitting on cushions, chanting sutras, or offering incense. Most of us recognize this as being “Zen-like” and know that it is serious business. But what else is there to this behavior? What is Zen’s less formal side? When do “serious practice” and “real life” either join or separate? And just how serious do we have to be?

Whenever I cook dinner, one of my favorite actions is deglazing the pan. With a small amount of liquid and an adequate level of heat, a cook can transform the burned crust of residual ingredients on the bottom of a skillet into a flavorful and free-flowing elixir. That which was hard, stubborn, and resistant becomes soft and unstuck. This is also a workable recipe for Zen gravy: with a fluid balance of meditation and work practice, we can allow ourselves to become unstuck. And by “unstuck” I mean to say independent. We are indeed connected to all things, but we should feel free to move about, free to join others, free to examine preconceptions and misinterpretations, and free to find our Buddha-nature as we engage in the day’s most common actions and events.

Housework is a chance to approach your life with integrity. Washing soiled laundry and cleaning out cupboards are not duties given to you as acts of penance. Each forms a vital part of your well-being. Each activity you perform is an opportunity to observe the ways mind and body can work together and how they can sometimes conflict. The mind can spend hours worrying about a simple task that will take the body only minutes to perform. Although the music may be long, the dance itself is short.

Through art, a painter can make the ordinary come alive. As Zen students, we try to bring this kind of relevance into each moment of our lives, into this one moment that contains all moments. In this way, we allow the ordinary to enliven us. Sometimes this is successful, sometimes not, but the work itself goes on. Persistence is one of the major virtues in both the artist and the unenlightened.

By fully engaging in each of the day’s activities, we can help keep the words of Pai Chang alive. Whenever you address the dust and clutter close by, you take a step toward increasing your understanding. Ultimately, this one step can lead you toward that crucial point in your practice when you realize that toothpaste in the sink and coffee-stained linens are not just here to ruin your day. As you encounter each of these situations directly, with patience and good humor, you’ll discover renewed respect for your work. And you’ll approach this dusty world with a mind clear as glass.

Ready to get started?

The following are some practical tips on how to approach various housekeeping tasks with mindfulness, adapted from Gary Thorp’s book, Sweeping Changes: Discovering the Joy of Zen in Everyday Tasks.

Dusting

Dusting

Use the time you dust to enhance your sense of touch. You can experience a feeling of intimacy with the things in your environment by caressing the various objects before you, becoming familiar with their shapes once again and remembering how they came into your life. As with sweeping, make sure that you give your full attention to those areas that would be easy for you to hurry over or to abandon entirely. The idea is not to go over or around things but to go into them.

Sweeping

The next time you sweep the floor, try to move with deliberation, feeling both the support of the floor beneath your feet and the protection of the ceiling overhead. Try to sense the differences between rooms and to be aware as you move from area to area and from environment to environment. Notice the different qualities of light and the variations of shadows. And experience both the fragility and the strength of your own body as it goes about its common work. If you move the broom from left to right as well as from right to left, the broom will wear more evenly and, in the process, you’ll experience two different sides of yourself. You may notice some awkwardness when you first turn the broom around, just as you feel a bit ill at ease whenever you change your perspective on things. Try to stand a different way or to hold the broom in a different way to see what else happens. Start to give more attention to the floor’s edges and corners. Think about your own shadowed areas as well as those that are out in the open.

Making the bed

As you air out your own sheets and blankets, you can be grateful for the fresh-smelling aroma and sunshine that permeate them. As you plump the pillows, try to remember the dreams that were born upon them. As you smooth the wrinkles from the top layer of bedding, you can consider the waking world. What does it mean to come fully alive? How do you change as you prepare to go out and encounter others? What do you leave behind? Now that you are embarked on your life again, it is the bed’s opportunity to rest. Perhaps you can take some of its comfort with you.

Dishwashing

Wash the dish. Totally. Hold nothing back. Feel the warmth of the water. Look at the reflection of the light on the surfaces of things. Let your fingers touch the sides of the knife blade, the flat of the spatula, the rim of the dishpan. Don’t think about things. These thoughts are merely distractions and diversions from what it is you’re really doing. Feel what you are actually holding in your hands. Feel the genuine energy of your body as it engages in this activity. Notice the different materials that your dishes and utensils are made from. Concentrate on simply washing, rinsing, and drying each spoon and plate, and you will begin to develop your own individual style of handling things. When you wash and dry a single spoon and give it your full attention, you are expressing care for the entire universe.

Window-washing

Taking care of your windows can be a richly rewarding experience, especially if you clean your windows on a sunny day. You can feel the warmth of the sunlight radiating toward you from far away. As you attend to this cleaning, you might wonder about what you’re seeing. What do you look for when you seek more clarity in your life? What is it that interferes with experiencing this clarity? How far does clarity extend? And while cleaning windows primarily engages your sense of sight, there are sounds to experience as well. Listen to the sounds of the squeaking as your cloth wipes the glass and the sound of dripping water as you wring out the washing cloth. By concentrating on the simple wiping motion of the washcloth, you may begin to feel the origins of your own emancipation.

Putting things away

Position shorter items in front of taller ones. Place lighter things on top of heavier ones. Protect the fragile object from hard, neighboring items that might harm it. Store each thing carefully, giving attention to the fact that there are differences between caring for something by putting it in a safe place, and hoarding it or imprisoning it. Storing items poorly or forgetting about them is no different from abandonment. Even if something is being put away for a great length of time, visit it from time to time, remembering how it came to you, reminding yourself of its value, and checking on its condition. Make periodic inventories of any new possessions that you’ve acquired. Lay them out and look at them. Don’t be afraid to acknowledge mistakes you may have made in selecting them. Above all, don’t ignore what you have.

♦

From Sweeping Changes: Discovering the Joy of Zen in Everyday Tasks, © 2000 by Gary Thorp. Reprinted with permission of Walker & Company.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.