Even though we practice, we continue to fall for pleasant feelings. Feelings are illusory on many levels. We don’t realize that they’re changeable and unreliable. Instead of offering pleasure, they offer us nothing but stress—yet we’re still addicted to them. This business of feeling is a very subtle matter. Please try to contemplate it carefully, this latching onto feelings of pleasure, pain, or equanimity. And you have to experiment with pain more than you may want to. When there are feelings of physical pain or mental distress, the mind will struggle because it doesn’t like pain. But when pain turns to pleasure the mind likes it and is content with it. So it keeps on playing with feeling even though, as we’ve already said, feeling is inconstant, stressful, and not really ours. But the mind doesn’t see this. All it sees are feelings of pleasure, and it wants them. Try looking into how feeling gives rise to craving. It’s because we want pleasant feelings that craving whispers—whispers right there to the feeling. If you observe carefully, you will see that this is very important. This is where the paths and fruitions leading to nibbana are attained. If we extinguish the craving in feeling, that’s nibbana.

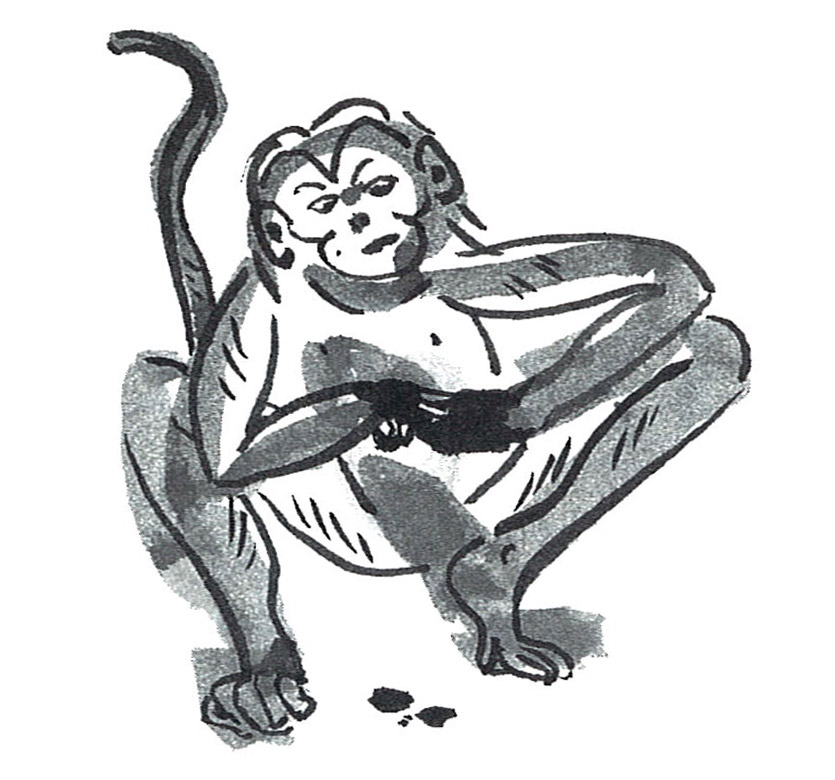

We’re stuck on feeling like a monkey stuck in a tar trap. A glob of tar is placed where a monkey will get its hand stuck and, in trying to pull free, the monkey gets its other hand, both feet, and eventually its mouth stuck, too.

The Buddha said that defilement [mental qualities that obscure the clarity of the mind: passion, aversion, delusion] is like a wide and deep flood. But then he went on to describe the practice of crossing that flood as simply abandoning craving in every action. Now, right here at feeling, is where we can practice abandoning craving.

Bring the practice close to home. When the mind changes, or when it gains a sense of stillness or calm that would rank as a feeling of pleasure or equanimity, try to see in what ways the pleasure or equanimity is inconstant, how it’s not you or yours. When you can do this, you’ll stop relishing that particular feeling. You can stop right there, right where the mind relishes the flavor of feeling and gives rise to craving. This is why the mind has to be fully aware of itself—all around, at all times—in its focused contemplation, to see feeling as empty of self.

This business of liking and disliking feelings is a disease difficult to detect, because our intoxication with feelings is so very strong. Even with the sensations of peace and emptiness in the mind, we’re still infatuated with feeling. Feelings on the crude level—the violent and stressful ones that come with defilement—are easy to detect. But when the mind grows still—steady, cool, bright, and so on—we’re still addicted to feeling. We want these feelings of pleasure or equanimity. We enjoy them. Even on the level of firm concentration or meditative absorption, there’s attachment to the feeling.

This is the subtle magnetic pull of craving, which paints and plasters things over. This painting and plastering is hard to detect, because craving is always whispering inside us, “I want nothing but pleasant feelings.” This is very important, because this virus of craving is what makes us continue to be reborn.

We’re stuck on feeling like a monkey stuck in a tar trap. A glob of tar is placed where a monkey will get its hand stuck and, in trying to pull free, the monkey gets its other hand, both feet, and eventually its mouth stuck, too. Consider this: Whatever we do, we end up stuck right here at feeling and craving. We can’t separate them out. We can’t wash them off. If we don’t grow weary of craving, we’re like the monkey stuck in the glob of tar, getting ourselves more and more trapped all the time. So if we’re intent on freeing ourselves in the footsteps of the arahants, we have to focus specifically on feeling until we can succeed at freeing ourselves from it. Even with painful feelings, we have to practice—for if we’re afraid of pain and always try to change it to pleasure, we’ll end up even more ignorant than before.

This is why we have to be brave in experimenting with pain—both physical pain and mental diseases. When it arises in full measure, like a house afire, can we let go of it? We have to know both sides of feeling. When it’s hot and burning, how can we deal with it? When it’s cool and refreshing, how can we see through it? We have to make an effort to focus on both sides, contemplating until we know how to let go. Otherwise, we won’t know anything, for all we want is the cool side, the cooler the better.

Nibbana is the extinguishing of craving, and yet we like to stay with craving—so how can we expect to get anywhere at all? We’ll stay right here in the world, right here with stress and suffering, for craving is a sticky sap. If there’s no craving, there’s nothing: no stress, no rebirth. But we have to watch out for it. It’s a sticky sap, a glob of tar, a dye that’s hard to wash out.

EMPTINESS VS. THE VOID

To open the door so that you can really see inside yourself isn’t easy, but it’s something you can train yourself to do. If you have the mindfulness enabling you to read yourself and understand yourself, that cuts through a lot of issues right there. Craving will have a hard time forming, In whatever guises it arises, you’ll get to read it, to know it, to extinguish it, to let it go.

When you get to do these things, it doesn’t mean that you “get” anything, for actually once the mind is empty, that means it doesn’t gain anything at all. But to put it into words for those who haven’t experienced it: In what ways is emptiness empty? Does it mean that everything disappears or is annihilated? Actually, you should know that emptiness doesn’t mean that the mind is annihilated. All that’s annihilated is clinging and attachment. What you have to do is to see what emptiness is like as it actually appears and then not latch onto it. The nature of this emptiness is that it’s deathless within you—this emptiness of self—and yet the mind can still function, know, and read itself. Just don’t label it or latch onto it, that’s all.

There are many levels to emptiness, many types, but if it’s this or that type, then it’s not genuine emptiness, for it contains the intention of trying to know what type of emptiness it is, what feature it has. If it’s superficial emptiness—the emptiness of the still mind, free from thought-formations about its objects or free from the external sense of self—that’s not genuine emptiness. Genuine emptiness lies deep, not on the level of mere stillness or concentration. The emptiness of the void is something very profound.

But because of the things we’ve studied and heard, we tend to label the emptiness of the still mind as the void—and so we label things wrongly in that emptiness. We have to look more deeply within, No matter what you encounter, don’t get excited, Don’t label it as this or that level of attainment. Otherwise you’ll spoil everything, You reach the level where you should be able to keep your awareness steady, but once you label things, it stops right there—or else goes all out of control. This labeling is attachment in action.

So to start out, simply watch these things, simply be aware, If you get excited, it ruins everything, You don’t see things clear through, You stop there and don’t go any further. For this reason, when you train the mind or contemplate the mind to the point of gaining clear realizations every now and then, regard them as simply things to observe.

♦

Reprinted with permission from An Unentangled Knowing: The Teaching of a Thai Buddhist Lay Woman (Dhamma Dana Publications), Translated from the Thai by Thanissaro Bhikkhu.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.