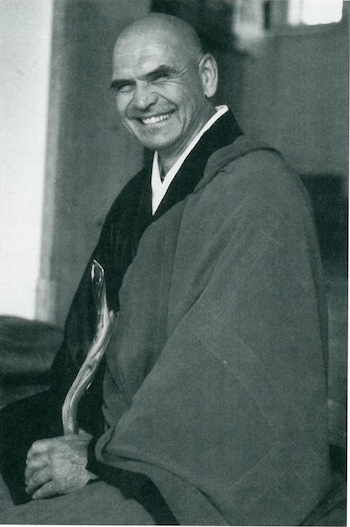

Roshi Bernard Tetsugen Glassman stands with an attendant before the zendo altar, exuding massive concentration under the burden of heavy formal robes in the heat of an Albuquerque summer. As scores of guests crowded into Hidden Mountain Zen Center for the Buddha Eye Opening dedication ceremony look on, he slowly drops a pinch of incense into a burner. It bursts into a fragrant cloud. Then the new Zen center’s abbot, Sensei Alfred Jitsudo Ancheta, a native New Mexican, takes his dharma brother’s place at the altar to perform a memorial service for their late teacher, Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi Roshi. Ancheta executes the ritual movements with exquisite care. “Right here now as this river-mountain-sky-desert-swamp-ocean Roshi!” he declares. “Why don’t we see your body here in this zendo?”

And so, on a July morning in 1996, this 110-year-old brick house on a downtown side street officially became a new Zen center. It was a watershed moment. Ancheta has the rare distinction of being a Hispanic teaching the dharma in America. His decision to take up residence in the land of his ancestors signals a homecoming, the belated return of a native son. At a time when many U.S.-born Buddhists openly worry that Buddhism is becoming too much an Anglo, middle-class phenomenon, Ancheta is sharply conscious of the need to present the dharma to a wider audience. At fifty-three, he has a focused manner and an unexpectedly searching, almost hesitant way of speaking. His deep-set brown eyes, under black, bushy eyebrows, vacillate between penetrating, hawklike intensity and avuncular warmth and humor. Says Ancheta, “I have very strong pioneer roots.”

Pioneering—literal and metaphorical—has defined Ancheta’s journey away from home and back again. He was born in Embudo, New Mexico, a tiny spot along the Rio Grande on the road to Taos, yet like thousands of other New Mexicans of the postwar generation, his father found work in southern California and the family relocated to the suburban sprawl of Long Beach. Young Freddy Ancheta spent summers with his maternal grandparents in the village of Velarde, a quiet place of orchards and hayfields along the river where it spills out of a deep canyon.

Just south of Velarde lies San Juan Pueblo, where Don Juan de Onate established the earliest Spanish settlement in New Mexico in 1598. Chafing under religious and economic repression, the people of San Juan and most of the other Pueblos rose up against the Spanish conquerors in 1680 and drove them from the territory. Spanish dominion was restored only in 1692, when Don Diego de Vargas returned at the head of an army. According to family lore, Ancheta’s mother was descended from de Vargas.

His father’s family came from Silver City, in rugged southwestern New Mexico. An ancestor, Nepomuceno Ancheta, arrived in the territory in 1856 fleeing the Mexican Revolution. His son Joseph, who became an attorney and a member of the Territorial Legislature, was assassinated on the floor of the state senate, the unintended victim of a plot to murder territorial power broker Thomas B. Catron. “He caught a stray bullet,” Ancheta says of his great-grandfather.

Ancheta’s maternal ancestors were shaped by northern New Mexico’s Catholicism, a conservative, strongly devotional faith, honed by centuries of isolation from the rest of the Spanish-speaking world. New Mexico Catholics preserved a deep belief in the intercessional powers of the Virgin Mary and the saints. It was a worldview that did not encourage people to look elsewhere for answers. “When I was involved in Christian churches as a teenager, I can specifically remember hearing people say Buddhism was for idol-worshipers,” Ancheta says. “‘They bow to Buddha—they bow to images.’”

But by his mother’s generation, she and some of her siblings were attending Protestant churches. “My mother’s personal commitment was to spirituality, not religion,” Ancheta recalls. “She encouraged me to go to as many different kinds of churches as I wanted.”

Ancheta wants to offer Buddhism to New Mexico’s burgeoning Hispanic population. In most American sanghas, he notes, “you don’t see many minorities—one or two. If you’re hungry, you don’t have a chance to look into other forms of philosophy or religion.” He envisions taking advantage of his ethnic heritage, both by teaching the dharma to Hispanics and by reaching out to kids in trouble.

He tells of a teenage boy he’s been working with who’s struggling with the temptations of joining a gang. The boy’s mother, suspicious of the shaven-headed stranger, had a friend look into his family’s background in Velarde. “She called me to let me know she’d been checking up on me,” Ancheta says. “She said, ‘Your uncle can’t praise you enough.’”

Many Hispanics, with their strong Catholic background, shy away from Buddhism because they feel it clashes with orthodox Christianity. At Hidden Mountain, Ancheta continues, “we have one lady who has been struggling with herself whether she should do this or not.” He has encouraged her to consult Pat Hawk, a Catholic priest who also teaches Zen and who travels from his home in Amarillo, Texas, to work with students in Santa Fe.

Ancheta’s maternal aunt, Zoraida Ortega, and her husband, Eulogio, live in an old adobe house in Velarde. “Aside from Thich Nhat Hanh, if I’ve ever met a saint, it’s my uncle and my aunt,” Ancheta says. “They’re filled with gentleness and an extreme humbleness about what they do.”

When Eulogio retired as a school principal, he took up the traditional practice of carving santos—painted wooden likenesses of the saints. This craft dates back centuries to a time when territorial churches could not obtain plaster statues from Europe. The tradition lapsed after railroads arrived in the late ninteenth century and opened the region to the outside world, but it has been revived over the past twenty-five years as an expression of spiritual renewal. Contemporary santeros carefully study the techniques of the old masters. Some even try to replicate the traditional paints made from locally available natural pigments.

“When I was young, I wanted to be a schoolteacher so I could be like him. Way back in the 1950s, he started doing hatha yoga,” Ancheta remembers. “He told my father about the benefits of standing on his head. By the seventies he started practicing zazen.” Ancheta and Eulogio exchanged books on Zen for years.

“The things he says are very Buddhist to me,” Ancheta muses. “He says he takes a piece of wood and he sits with it and meditates with it. He thinks about the saint.” Because his uncle is color-blind, his aunt, a retired schoolteacher, has the job of painting each santo. “She says the same thing. She sits with the saint and asks him what color to use.”

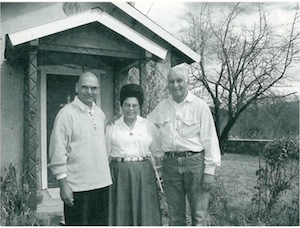

On a winter afternoon, Ancheta hops in his white pickup and heads north to Velarde. Driving slowly along a dirt road leading into the village, he stops before a whitewashed Methodist church with a red tin roof and points to a small neighboring building, where he attended first grade. Turning down a narrow lane, he pulls up to a flat-roofed house. Eulogio Ortega, clad in denim shirt and jeans, his snow-white hair swept back, comes out to greet his nephew. A moment later Zoraida appears and gives Ancheta a quiet embrace.

Their small living room holds an exquisite collections of retablos—painted images of the saints—and santos, some carved by Eulogio, representations of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patron of Mexico, along with crucifixes of the sort Eulogio has made and donated to local churches. The figures have elongated faces and limbs with moving, melancholy expressions. “Some of these old ones are very, very effective,” offers Eulogio. “There’s something about them. The old santeros could care less about the body dimensions. They were more interested in bringing a certain religious expression.”

His uncle gives Ancheta a Catholic magazine chronicling the late Thomas Merton’s encounter with the Dalai Lama in the 1960s. Eulogio, it seems, about ten years ago attended a Christian-Buddhist workshop at the Naropa Institute at which the Dalai Lama spoke. “I read a little about Zen,” he says modestly. “I’ve always been interested in Eastern religions.” He laughs. “I’ve always been interested in religion, you know? I do a lot of praying on my own.” Later, he and Zoraida put on their coats and take their visitors outside to the adobe chapel he built for her in their front yard fifteen years ago. It is filled with beautifully carved santos.

A spiritual seeker like his uncle, Ancheta took years to figure out what he wanted to do with his life. Seeking to avoid Vietnam, he enlisted in the Army in 1965 and was stationed in Europe. Later he studied sociology at California State University at Fullerton, where he met his first wife, and studied briefly with a Hindu teacher. After his military stint and the social and racial turmoil of the 1960s, Ancheta was lost. “All the things I believed in seemed irrelevant.” Somewhere along the way, he had read a little about Buddhism in a religion course. “It intrigued me,” he says. “What I was trying to do was understand myself: ‘Who am I? What is the meaning of all this?’”

In 1970, a friend in L.A. told him, “There’s a real Zen teacher here.” Ancheta first encountered the monk who would become his teacher when he entered the zendo at the Zen Center of Los Angeles and realized someone else was already sitting there—Maezumi himself. “‘Taizan’ means ‘mountain,’” Ancheta says. “When I first saw him, I just got this wave of ‘This is a mountain.’ It just stopped me in my tracks.”

After two years of sitting weekends and sesshins at ZCLA, Ancheta and his wife moved to British Columbia, where they built a log cabin in the wilderness and tried to create a Zen community. Lacking electricity, the house was heated with wood, and they drew water from a hand-dug well. “I was very idealistic in thinking I could start a Buddhist community in British Columbia on my own,” he says. “But I very quickly saw my own immaturity and starting returning more and more often to Maezumi. By 1978, I was visiting British Columbia from Los Angeles.”

Ancheta took tokudo—formal vows—in January 1982. His father and uncle attended the ceremony. A few months later, Maezumi sent his new monk to a remote, 160-acre forested tract in the San Jacinto Mountains east of Los Angeles. Ancheta, whose marriage was ending, threw himself into building what would become Zen Mountain Center. Mountain Center became Maezumi’s rural retreat, with Ancheta serving as administrator and viceabbot. Over time, it acquired a zendo, a Buddha Hall for dining and chanting, a dormitory and dokusan building, a bath house, and private cabins.

In an effort to raise funds and make Mountain Center socially relevant, Ancheta developed his Inward Bound program. There were two-day workshops to introduce guests—teens, psychotherapists, HIV-positive patients—to secularized Buddhist principles. “It was essentially teaching Zen practice without the jargon,” he says. “A lot of people who came to them became Zen students.”

In 1992, Ancheta received dharma transmission from Maezumi Roshi. He was now authorized to conduct daisan – formal interviews and koan practice – with Maezumi’s students, and to cultivate students independently. Meanwhile, Ancheta had remarried to a Zen student and schoolteacher, with whom he had a daughter.

But early in 1995, the sangha learned Ancheta had had an affair with another student. His marriage broke up, he lost his post as administrator and viceabbot and he was asked to take a six-month leave.

“I was very controlling,” he says, shaking his head at the memory. “I had a lot of leeway. I did a lot of things without asking for permission. This isn’t an excuse,” he continues. “What I did in having an affair was ignorance on my part—a lack of wisdom and a lot of ignorance. It caused a lot of people a lot of grief, and I regret that.”

In May 1995, Maezumi died unexpectedly. By that time, Ancheta had resolved to leave Mountain Center and establish himself as a teacher elsewhere. “It’s hard to say, but it’s the truth,” he says. “It’s the best thing that ever happened to me. I had become so comfortable as a teacher that had I stayed, I probably would’ve become very dull. Having to shift and start over has been very good for me. It also made me see myself in a very different way.”

A month before Maezumi’s death, Ancheta bought a two-story Victorian house in Albuquerque. His board of directors consisted of two couples—friends who weren’t students of his. “I told them, whatever developed I wanted it to be bigger than myself,” Ancheta says. “They had to take an active role in leadership.”

The first test of the new arrangement had to do with the very location of the new Zen center. “I wanted a country site,” says Ancheta, who describes himself as “a hermit” by nature. But this time he acquiesced to the judgment of others. “The board of directors and I discussed it and decided we should be in the city.”

The old building needed an overhaul. Working with volunteers, Ancheta installed a kitchen; walls were knocked out and an oak floor laid for the zendo. Upstairs, bedrooms were converted to dormitory space for sesshins and resident students. Ancheta moved into a small cottage out back. By the spring of 1996, the opening of Hidden Mountain Center was advertised nationally. (Its name, suggested by a board member, had come from Dogen’s Shobogenzo.) The broad advertising was mostly to let former students know of the new location. Initially, Ancheta did not advertise in Albuquerque. “I didn’t do anything locally because I just wanted to see what would happen, just letting people find us,” he says.

In the year since its dedication, Hidden Mountain has attracted many local people, some of whom are doing koan practice with the teacher. Ancheta continually recalls the example his late teacher set. “He really gave of himself,” he says of Maezumi. “People used to ask him what happened to us after we die,” Ancheta says. “He’d say, ‘If anything lives longer than us, it’s our vow.’”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.