The Pali word metta, based on a word meaning “friend” or “friendship” (mitra), is usually translated as “lovingkindness.” This is a quality of mind or an intentional emotional stance of kindheartedness, benevolence, and goodwill. It can arise at any time, in relation to any object. One might feel lovingkindness when gazing at a pet, hearing a favorite song, or thinking of a good friend. It is natural to feel this emotion toward some people and not others, in some situations and not others, or only when one is in certain moods. Multiple factors condition what arises in experience at any moment, and, accordingly, sometimes metta is present in the mind and sometimes it is not.

The Buddhist practice of lovingkindness meditation, or metta bhavana (literally “causing lovingkindness to be” in Pali) encourages the development of metta. Metta bhavana asks you to first evoke and then sustain a benevolent attitude for many moments at a time, thus encouraging it to arise within you steadily and without interruption. The practice has the effect of blocking out hatred (since love and hate cannot exist in the mind at the same time) and strengthening the roots of kindness within you.

In metta bhavana practice, you call to mind a person toward whom you already feel friendly and repeat phrases that support a benevolent intention for that person, such as “May they be happy; May they be well; May they be free from harm.” Gradually, you expand the field from that person to include friends, relatives, acquaintances, strangers, and, eventually, all beings.

Wait a minute—all beings? Does this mean we have to love Hitler, or Caligula, or Genghis Khan? And surely there are people alive today whom we don’t like and who have shown themselves to be undeserving of our respect and goodwill. Do we have to direct our lovingkindness to them?

Yes, the Metta Sutta says, toward everyone, without exception (anavasesa). Metta is to be directed toward all beings (sabbe satta), all who have come to be (sabbe bhuta), with a mind unbounded toward the entire world (sabbaloka), with “no holding back, no loathing, no foe”—even people we don’t like. But why?

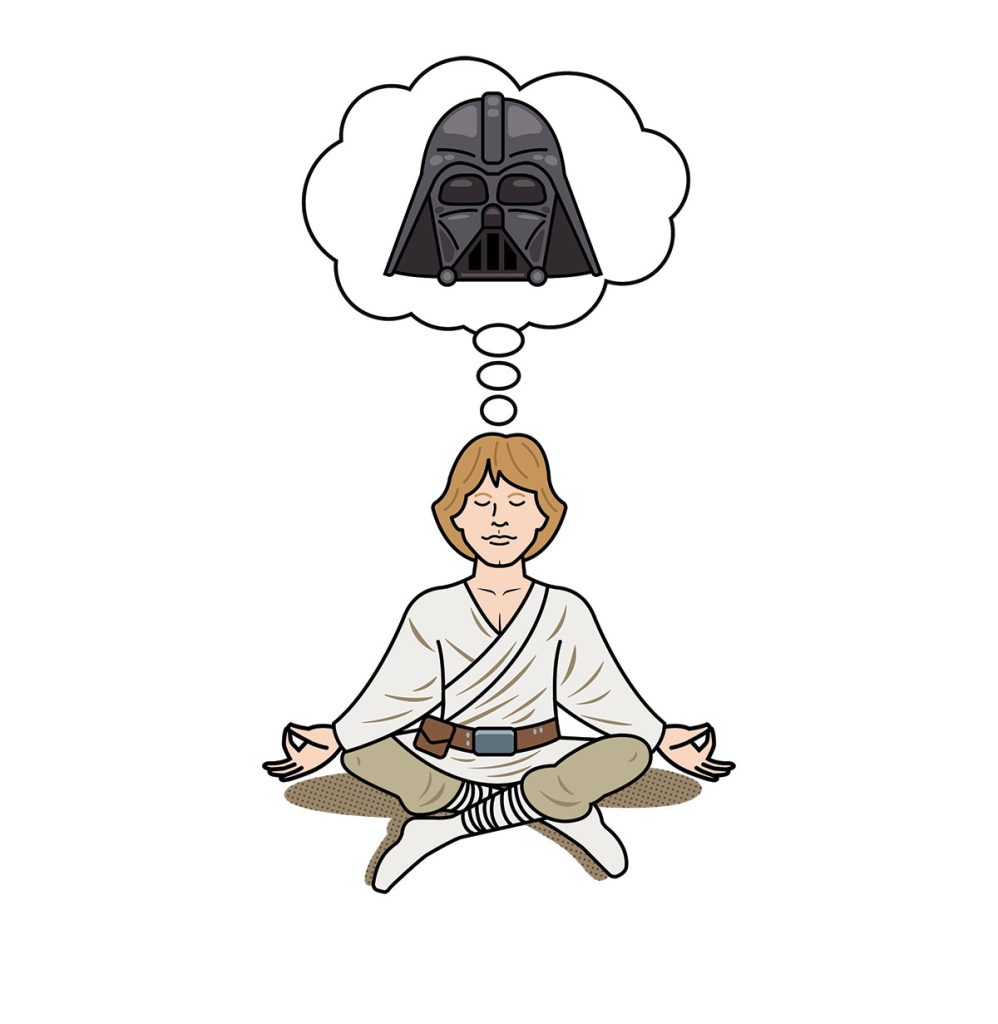

Simply stated: metta practice is not about them; it is about you. You do not love other people because they deserve it or because there might be a spark of goodness in the hardest of hearts. The practice of lovingkindness is for cleansing your own mind stream. It is a healthy mental and emotional state, and the more often you can conjure it up and sustain it over time, the better off you are. While radiating lovingkindness in all directions, to all beings, without exception, your conscious mind is bright and luminous, dwelling in a holy or godlike state (brahma-vihara), and your unconscious mind is being subtly transformed such that you are becoming a kinder person, one who will be more disposed to respond with lovingkindness in the future. In order for the intentional development of lovingkindness to reach fulfillment and become truly transformative, the feeling of friendliness has to encompass everyone.

Hatred, on the other hand, is inherently toxic, and anytime it emerges from the depths of the psyche and flows into your active mind, it causes harm. Hatred affects others when you act upon it by assaulting or berating them; the state of hatred itself also causes lasting damage to the quality of your own character. Enacting even low doses of hatred such as annoyance or disapproval reinforces a toxic quality of mind and hampers your ability to love. There is a lot that is wrong with our world, but attacking the things we don’t like with malice will always lead to harm in the long run. The Buddha offers the image of a person thrusting a torch at someone upwind: the intention is to harm the other, but the torchholder is the one who gets burned.

Lovingkindness is the antidote to hatred. That is why cultivating it is so beneficial. The practice is about your being able to access and cultivate the healthiest parts of yourself, without allowing anyone to obstruct that. Why should the indisputable fact that someone is a jerk—or even a monster—drag you down and prevent you from becoming a better person? Why can’t the lovingkindness you are generating permeate even the darkest corners of this world?

Lovingkindness is universal, not personal. This is what makes it so powerful as a tool for mental purification and emotional transformation. Let’s even extend it to, and perhaps especially to, the jerks and monsters of our world.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.