The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice:

First Journals and Poems 1937–1952

Allen Ginsberg, edited by Juanita Lieberman-Plimpton and Bill Morgan

Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2006

523 pp.; $27.50 (cloth)

Collected Poems 1947–1997

Allen Ginsberg

New York: HarperCollins, 2006

1,189 pp.; $39.95 (cloth)

Howl [Annotated]

Allen Ginsberg, edited by Barry Miles

New York: HarperPerrenial, 2006

194 pp.; $18.95 (paper)

I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg

Bill Morgan

New York: Viking, 2006

720 pp.; $29.95 (cloth)

Twenty-five years ago, while explaining his method of spontaneous composition, Allen Ginsberg stated that “it [was] possible to get in a state of inspiration while improvising.” He often improvised during poetry readings, using an already published poem such as “America” as the framework for lengthy new improvisations, similar to the way jazz musicians used a song as the framework for extended solos. It was much more difficult, Ginsberg allowed, to accomplish this when he was actually writing. Longer works such as Howl or Kaddish, two masterworks generally acknowledged as towering examples of Ginsberg’s skills in spontaneous composition, required a lot of ingredients coming together at once.

“You have to be inspired to write something like that,” he said. “It’s not something you can very easily do just by pressing a button. You have to have the right historical and physical combination, the right mental formation, the right courage, the right sense of prophecy, and the right information, intentions, and ambition.”

A handful of recently published books, released to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the writing and publishing of Howl, provide fresh and welcome insight into this crucial combination of factors behind one of the great achievements of American literature. The story of the writing of Howl has been told and retold by Ginsberg, most notably in his recently reissued annotated edition of Howl, but all too often a very important fact is lost in the telling: while Ginsberg did indeed sit down at his typewriter and, in a single extended work session, compose the massive main body of one of the most influential poems of the twentieth century, he did not do so by simply pressing a button and unleashing what his friend and mentor William S. Burroughs called a “word horde.” Ginsberg was twenty-nine in 1955 when he wrote Howl, and every one of those twenty-nine years seems to have acted as an unwritten preamble to the poem.

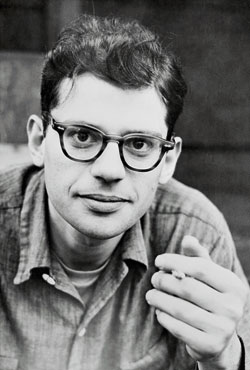

The author of Howl was not the same Allen Ginsberg that the public came to know later in his life, after he’d reached his iconic level of fame. He wasn’t the confident, long-haired, politically-charged and savvy figure depicted in Fred McDarrah’s famous “Uncle Sam top hat” photo, or the suited, professorial Ginsberg captured by Robert Frank for later book jackets. The youthful Ginsberg was a holy mess of psychological, intellectual, and artistic characteristics and ambitions, often in conflict yet always seeking the correct (as opposed to proper) form of expression.

“I’m writing to satisfy my egotism,” he wrote in 1941, shortly before his fifteenth birthday. “If some future historian or biographer wants to know what the genius thought and did in his tender years, here it is. I’ll be a genius of some kind of other, probably in literature. I really believe it. (Not naively, as whoever reads this is thinking.) I have a fair degree of confidence in myself. Either I’m a genius, I’m egocentric, or I’m slightly schizophrenic. Probably the first two.”

Not surprisingly, this and similar entries embarrassed the adult Ginsberg to such a degree that he refused to allow his youthful journals to be published until after his death. Bill Morgan and Juanita Lieberman-Plimpton started compiling and editing Ginsberg’s The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice nearly two decades ago, and these journals, along with Morgan’s excellent new biography, I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg, ultimately serve as guides to the long, painstaking, and often painful journey leading to the composition of Howl.

Ginsberg’s childhood and adolescence, recalled in excruciating detail in Kaddish and other later poems, and recounted in Morgan’s biography, caused William Carlos Williams to marvel that Ginsberg had survived long enough to write Howl. As a boy, Ginsberg watched his mother, Naomi, a Russian immigrant, drop deeper and deeper into an abyss of paranoid schizophrenia; she would be in and out of mental institutions for much of her adult life, and even today it’s hard to tell which was more difficult on her youngest son. His father, Louis Ginsberg, a teacher and moderately successful poet, labored to raise a family on a modest salary while trying to fulfill his own poetic aspirations. It wasn’t easy, to say the least. It grew even more difficult for the young Allen Ginsberg when he became aware of his homosexuality and suffered the psychological penalties for trying to hide it from an intolerant society. When he enrolled at Columbia, Ginsberg had just turned seventeen, and while he might have been intellectually capable of taking on formal university studies, he was emotionally lagging behind his peers. He desperately needed love, but he didn’t dare pursue it. He wanted to write poetry, but he couldn’t even discuss it with his own father, since Louis Ginsberg had always joked that poets weren’t normal.

Three Columbia professors—Lionel Trilling, Mark Van Doren, and Raymond Weaver—recognized Ginsberg’s potential and offered encouragement, albeit in the traditional academic sense. More important, Ginsberg met Lucien Carr, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs, each bright but unconventional thinkers, each filling his head with attitudes and ideas completely alien to anything he had witnessed or experienced while growing up in Paterson, New Jersey.

Ginsberg’s formal and informal educations clashed. He didn’t dress (or care to dress) like his well-outfitted Ivy League classmates; he hung out with all the wrong people. Kerouac was persona non grata at Columbia, and when Ginsberg was caught housing him overnight in his dorm room, Columbia officials suspected the worst and drummed him off the campus. Ginsberg and Carr had tried to come up with what they called a “new vision” for literature—a form that, in an apocalyptic world, addressed real people in real situations in real language, literary models of the day be damned—but all Ginsberg knew, from his father and his studies, were existing literary models. His early poems, now published for the first time in Martyrdom and Artifice, indicated an undeveloped poet with great command of form, but with only the vaguest clue as to how to marry it to content. Ginsberg loved Whitman, but since Whitman was out of favor in the poetry establishment, he chose to imitate Marvell and Donne. It didn’t work.

His life became still more complicated when he met Neal Cassady, the street-smart, self-educated, hyperkinetic, sexually supercharged “Western hero” who so enthralled Kerouac that he eventually devoted two major novels to him. Ginsberg saw him in a different light. He fell in love with the man first and the mind later, and, as would be the case throughout Ginsberg’s sexually confused life, the man he was intensely drawn to happened to be (mostly) heterosexual.

Ginsberg’s pursuit of Cassady, presented at great length in Martyrdom and Artifice, was both pathetic and heartbreaking. Here was a young man, pining like a teenage kid over his newfound love, hoping against all that he knew to be true that he would actually be able to find some miraculous solution to his homosexual yearnings. After arranging meetings under the guise of writing lessons, Ginsberg would sit alone in his room waiting for Cassady to arrive, only to learn that Cassady was jumping from woman to woman while he was keeping his lonely vigil. By the time Ginsberg was capable of accepting the truth, he was so psychologically and emotionally depleted that he had lost almost all of his self-respect—and he wasn’t all that far from losing his mind as well.

His friends and mentors weren’t faring well, either. Lucien Carr was behind bars, imprisoned for murdering David Kammerer, another Ginsberg acquaintance, who had been stalking Carr with the hopes of forcing him into a relationship. Kerouac, who had helped Carr dispose of evidence, had avoided a jail sentence by marrying and moving to Michigan. Burroughs, fed up with the New York scene, had relocated to Texas. And, if all that wasn’t taxing enough on Ginsberg’s frail state of mind, his parents had split up and Naomi Ginsberg was gradually sliding into such a mental decline that Allen would eventually be asked to sign papers authorizing his mother’s lobotomy.

Ginsberg teetered at the edge of his limits. He continued to write poetry with remarkable self-discipline, even as his daily existence crumbled and he himself began to question his sanity. His friends began to wonder as well, especially when, in 1948, Ginsberg announced to anyone who would listen that he’d had a series of “visions” rooted in William Blake’s poetry, visions that convinced him that he had a sacred vocation to pursue poetry and pass along the minute particulars of his life and experiences to future generations, just as Blake’s voice had been handed down through the ages.

At this point, a feature in Morgan’s biography becomes especially useful. HarperCollins has recently published a massive, 1,189-page, updated edition of Ginsberg’s Collected Poems, encompassing all of Ginsberg’s published poetry, and Morgan has included, in the margins of his biography, the titles of poems and their page numbers in Collected Poems corresponding with the events of Ginsberg’s life. Ginsberg always insisted that his poetry was a “graph” of his mind, and this feature in Morgan’s biography shows just how precisely this was so. The poems written immediately following Ginsberg’s “Blake visions” (“The Eye Altering Alters All,” “On Reading William Blake’s ‘The Sick Rose,'” “Vision 1948”) are too wrapped up in Ginsberg’s efforts to reproduce and analyze his visions to be effective as poems, whereas, a decade later, in “The Lion for Real,” he managed to be much more successful when he was not so self-conscious.

Ginsberg’s artistic development accelerated as his personal life dipped into a purgatory that would supply him with the grist for an epic poem. He was arrested after he allowed a group of petty thieves to use his apartment as a storehouse for stolen goods, and in a plea bargain with prosecutors, he chose time in a sanitarium over time in jail. While undergoing psychiatric evaluation, Ginsberg met Carl Solomon, the brilliant yet pathologically unconventional figure to whom Howl is dedicated. He also met and was befriended by William Carlos Williams, an acclaimed local poet well connected with the publishing world and much more suited to act as a Ginsberg tutor than anyone at Columbia. Williams encouraged Ginsberg to use American language and idiom in his poetry, and Ginsberg took the advice to heart.

The poetry written shortly after Ginsberg’s introduction to Williams, eventually published in 1961 in a volume of early poems, Empty Mirror, now published along with additional, previously unpublished poems in Martyrdom and Artifice, represent nothing less than a chrysalis between the derivative young Ginsberg and the fully realized poet he would become. Some of the work is still too self-consciously clever to represent anything other than an interesting exercise, but there are diamonds to be found as well, intimations that, for Ginsberg, content and form were finally coming together. The discovery was purely accidental. When Ginsberg tried to impress Williams by breaking lines from his journals into short poems similar to those written by Williams, the elder poet responded enthusiastically. He praised the work and promised to see it published. Ginsberg, like any eager young pupil beaming from his teacher’s praise, proceeded to break his journals down into a hefty volume’s worth of poems.

During this same period, Ginsberg’s spiritual growth took an unexpected turn when Jack Kerouac “discovered” Buddhism and suggested that his friend look into it. Ginsberg would always credit Kerouac for being the force behind his lifelong devotion to and study of Buddhism, but in reality Kerouac was far too preoccupied with his travels and writing for an in-depth study. Ginsberg, true to character, took a more scholarly approach, and while two decades would pass before Ginsberg would meet the Tibetan master Chögyam Trungpa and formally dedicate himself to Trungpa’s teachings, the initial studies proved significant, especially when he moved to San Francisco and met Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen, two poets who used Buddhism and Eastern thought as anchors in their work.

Ginsberg fled New York and an unsatisfactory attempt at a relationship with William Burroughs in 1953, and after spending nearly half a year in Mexico, exploring the Mayan ruins and writing Siesta in Xbalba (his first successful long poem) he returned to the States with the intention of reuniting with Neal Cassady, who had married and moved to San Jose. The reunion was short-lived. After Carolyn Cassady walked in on the two men in the midst of a sexual encounter, she loaded Ginsberg into the family car and dumped him off in San Francisco.

The city and its poetry community, as it turned out, were the final crucial ingredients necessary for the composition of Howl.

Beat Generation historians tend to employ a kind of shorthand in delineating Ginsberg’s early days in San Francisco: Ginsberg arrives in town; meets a psychologist who recommends that he give up his day job for poetry; begins a lifelong relationship with Peter Orlovsky; writesHowl and reads it at the legendary Six Gallery reading; and rockets to the forefront of a new generation of poets. As Morgan shows, it wasn’t really a quick, simple path from one point to the next. In fact, Howl might not have been written at all if Ginsberg hadn’t again backed himself into a corner. After Carolyn Cassady dropped him off in San Francisco, Ginsberg made a halfhearted attempt at living a “normal” life, taking up with a girlfriend and working a job, with predictable results. He was encouraged by a psychiatrist to drop the job and live an openly gay lifestyle if that would ease his mind, but it didn’t—not at first, at least. Peter Orlovsky, like Neil Cassady, was essentially heterosexual, and while he and Ginsberg agreed to maintain a mutually exclusive gay relationship, there were all kinds of troubles on the horizon.

Unhappy with the direction his life with Ginsberg was taking, Orlovsky left Ginsberg in the summer of 1955. Emotionally distraught, uncertain where his life was going, geographically removed from his closest friends and family, and discouraged by his own inability to get his work published, Ginsberg was again at a personal crossroads. Rather than lapse into another extended period of self-pity, he pondered the plights of those he knew to be in similar or worse condition—”best minds” that had been beaten down by society and circumstance, friends who had died (or, worse, were walking dead); friends who had suffered, people scarred by the marks of woe, as Blake would have it.

His life had led him to this moment. The long lines of the poem, which he initially entitled “Stropes” but then renamed Howl, were torrential outpourings, one leading easily to the next, devoted to actual events in his and his friends’ lives. Since he had no intention of ever publishing the work—it was too personal, as well as being far too sexually explicit for the times—he improvised as he went along, becoming more inspired with each line. Instead of writing something bathetic, as he might have done just a few years earlier, he chose to celebrate the lives he was depicting in the poem. The tone of his new work, oratorical and angry at first glance, was actually cathartic, almost ecstatic—proof that sympathy could unburden the spirit.

“I saw the best minds of my generation, destroyed by madness. . . .” He was thinking of all the others. He was thinking of his former self.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.