Greed and hatred are efficient survival tools. Deeply embedded in the operating system of sentient beings, perhaps from the days when a brain stem first developed in vertebrates, these instincts trigger behaviors that enable a creature to seek out and chase down the food it needs and to call forth the ferocity required to kill its prey or fight for its life. Each is an opposite expression of the same primordial force: desire. Greed is the desire to get and hold on to what one wants, while hatred is the desire to ignore or destroy what one does not want. They require little or no understanding, function best at rudimentary levels of consciousness, and thus thrive in conditions of ignorance and delusion.

Somewhere along the evolutionary continuum, something new seems to have been introduced into the software of sentient beings with the development of non-greed, non-hatred, and nondelusion. At some point it became adaptive to shift the focus of behavior from an entirely personal, self-oriented directive to get what “I” want at any cost, to a standpoint of cooperation, communication, and concern for the well-being of others in the herd or tribe. Kindness toward others, renunciation of personal gratification, and understanding the larger context all became powerfully effective tools for collective survival. Some creatures, especially humans, began nurturing the young, caring for the injured, assisting elders, and engaging in both small and large acts of self-sacrifice. And the species who did this thrived.

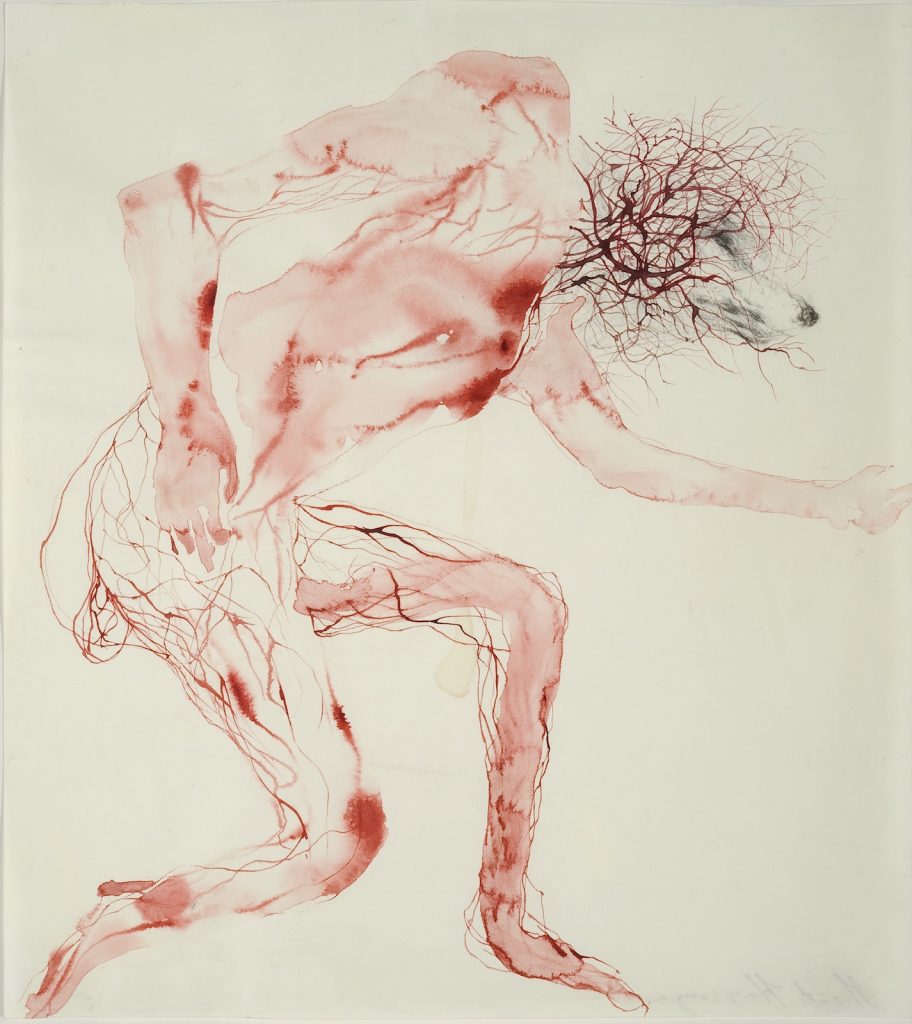

Here is the difficulty: the kinder, gentler responses did not replace the more primitive ones but were added on. The result is that we human beings regularly draw upon both layers to guide our behavior. Sometimes we act selfishly, hurtfully, and thoughtlessly, and sometimes we act with generosity, compassion, and wisdom. There are moments when we are oriented entirely toward getting what we want and avoiding what we do not want, even if we later feel remorse for doing so. We can’t help it. Somewhere deep inside us, the self needs to do whatever it needs to do to take care of itself. Then there are moments when we are happy to share, are spontaneously kind, see a larger good with clarity, and are capable of truly noble acts. This is just as instinctive, and can feel equally mysterious.

The Buddha recognized this bipolar aspect of human nature, referring to both the wholesome and the unwholesome impulses in ourselves. The words for these in Pali (kusala and akusala) do not mean “good and bad,” or “right or wrong,” but rather something like “healthy and unhealthy.” It is not only actions themselves that are understood to be either healthy or unhealthy, but also both the emotions that motivate actions and the personal consequences that derive from them. A kind act is rooted in the living emotion of feeling kindness toward someone, and the result of having committed a kind act is that one becomes a kinder person, more likely to feel kindness again. A hateful act is rooted in an emotion of aversion or ill-will toward someone, and by acting it out one becomes an incrementally more hateful person and strengthens the conditions for the reappearance of more hatred. It is by such entirely natural processes that we mold our personalities in a selfless world of cause and effect.

This being the case, ethics becomes a matter of skill. When we draw upon our more primitive reflexes, we tend to create suffering for ourselves and others, and when we act upon our more cooperative impulses, then both personal and collective suffering is diminished. The quality of our intention determines the quality of our disposition, which in turn determines the quality of our intention. If our goal ultimately is to be happier and to live in a better world, then it becomes skillful to abandon what causes harm and to develop what increases well-being. The opportunity to do this arises and passes away every moment.

The considerable mental and emotional powers that we possess as humans can be placed in the service of healthy or unhealthy impulses. We have amply demonstrated our ability to be greedy, hateful, and even ignorant in some truly brilliant and effective ways. But such actions are generally not healthy. By succeeding in getting what we want for ourselves in the short run, we often harm ourselves and others more deeply in the long term. Winning every battle, we slowly but surely lose the war. I think this accurately describes the current global predicament of the human species.

At the same time, those things that actually contribute most significantly to our well-being are often not immediately gratifying. It can seem like we are acting foolishly if we give up a personal advantage, help someone else fulfill their needs, or aim for accomplishing a transpersonal good. Yet events can reveal such acts of generosity, kindness, and understanding to be of great benefit for ourselves as well as for others. As with such martial arts as aikido, we can yield at every step and still wind up on top. Wisdom involves understanding cause and effect and thereby being able to see several moves ahead.

So what’s it going to be? Do we practice ignorance, by allowing our most unconscious instincts to guide our behavior by default? Or do we practice mindfulness, enabling the newest capacities of the prefrontal cortex to illuminate our actions with the light of awareness? The Buddha boldly pointed the way to the next step of evolution as lying along the path of greater awareness, which accesses not only our intelligence but a deeper capacity to care for one another. At stake is not only how skillfully we can act individually, bringing as much meaningfulness as possible to each of our lives, but also how skillful we will turn out to be as a species as we navigate the turbulent waters ahead. I would like to think that we can do a better job of it than the dinosaurs.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.