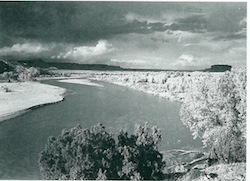

From its headwaters north of Crestone, Colorado south to Albuquerque, New Mexico, the northern Rio Grande region is becoming home to a distinctly southwestern Buddhism.

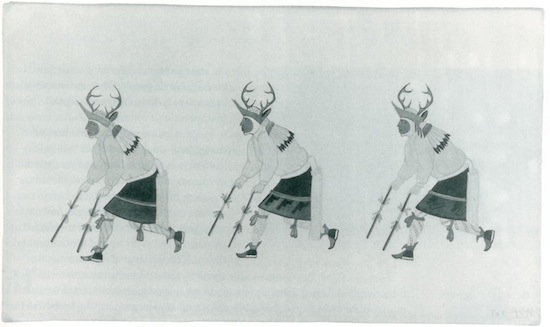

Drumbeats pierce the quiet of first light as fires appear at the top of a low mesa that hangs over the eastern edge of the pueblo of Jemez. The pink and yellow hues of the canyon are softened by the haze from the bonfires that line the roads winding between low adobe houses in the village. The people of the pueblo welcome Christmas morning as they have for as long as they have farmed corn along the river and hunted deer in the mountains.

From the smoke of one small fire comes a member of the Buffalo clan, his head covered in a hairy horned headdress, his bare chest smeared brown. Farther up the canyon, members of the Antelope clan, soft tails hanging from their belts, appear from the smoke of another fire.

The dancers gracefully descend from the hillside. They meet where the road enters the village and are showered with handfuls of dried corn, a sacrament delivered up from the land. Dancers and drummers face the eastern mesa, and Pueblo men sing an ancient prayer to welcome the rising sun.

The Pueblo people who were here first knew instinctively that spirit is tied to the land. Their rituals—annual, seasonal, and daily—invoke their surroundings. Mesas and mountains are places of worship.

The landscape in New Mexico and southern Colorado is tied tightly to spiritual practices. Corn, planted with a prayer in the dry soil of desert gardens, is essential to pueblo ceremonies from the Hopi mesas to the valley that holds the Rio Grande. Navajos draw prayers on the ground with colored sand, then blow the dirt clean at the ceremony’s end. Catholics, who in the 1600s, followed the Pueblo people into the Rio Grande Valley, still go to the forests for their saints, choosing cottonwood roots or pieces of aspen from which to carve santos—earthy, accessible images of the inhabitants of heaven.

And smoke from piñon fires is an unordained but powerful preacher whose sermon reaches Native Americans, Hispanic villagers, and Anglo newcomers from mountains to valleys on cold winter days.

Georgia O’Keeffe saw the light over the red cliffs of Abiquiu and never left, spending a lifetime painting bones, rock and flowers. D. H. Lawrence looked at the sky above the low, brown adobe village of Taos and said the view changed him forever: blue against brown; heaven and earth.

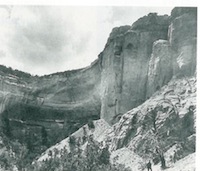

The people of Jemez Pueblo have recognized the transformational qualities since time immemorial. Twelve miles up the winding red-rock canyon from the present-day village, their ancestors bathed in geothermal hot springs and built a sprawling mesa-top settlement. On the mesa ledge above, an extensive complex of dirt and stone ruins once occupied by the Anasazi lies abandoned except for the ritual visits of their modern-day descendants, the Jemez.

Later, Spanish priests, tempered by the fires of a 750-year struggle to evict the Moors from their homeland, brought their austere Catholicism to this holy place. Now the adobe ruin of their mission church lies crumbling on one side of the winding mountain highway; a modern convent sits on the other. Spreading across the narrow canyon neck is Bodhi Mandala Zen Center.

In 1973 the first Buddhist practice center was established in the region when students of Rinzai Zen teacher Joshu Sasaki Roshi bought a Catholic retreat house in the village of Jemez Springs. Bodhi Manda had a zendo building, dormitories, and a dining hall set along the icy Jemez River. Best of all, the land had a natural hot spring, the same geothermal warming waters used by the early Pueblo people. When this was reported back to Sasaki Roshi, he supposedly said, “If you find hot spring, I come.”

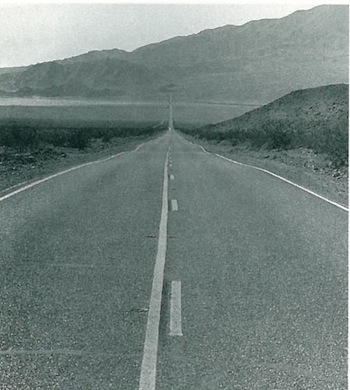

Poets, painters, and priests have been drawn to the high desert plain that links the flatlands of West Texas and the canyons of Arizona ever since train travel opened the region to the outside world. The region’s mountains, the valleys and rivers, combine to wrap around the soul of diverse travelers. It was train travel at the turn of the century and then U.S. 66, the ribbon of asphalt that began bringing travelers westward in the 1940s, that unfolded the formerly cloistered Southwestern landscape to new generations of pioneers and tourists alike. Most passed through. Some stayed, like the painters who found Taos in the 1930s and the bomb builders who founded Los Alamos in the 1940s.

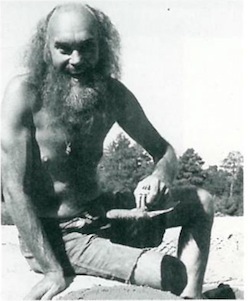

The magnet of the landscape began drawing a nascent Buddhist community from the front seats of VW bugs and the sleeping-bag-strewn backs of rattletrap vans that passed through northern New Mexico in the 1960s. The bellringers of the Age of Aquarius began to gather near Taos, on a strip of desert land between the 13,000-foot peaks of the Taos Mountains and the 650-foot-deep chasm of the Rio Grande Gorge. One of those who drove onto the Taos mesa back then was Jonathan Altman. He stopped and he stayed, founding and helping to build the Lama Foundation, a spiritual retreat center in the mountains north of Taos. Thirty years later, Altman can still feel the inexplicable pull of the landscape. “People come to Taos and immediately say, ‘This is where I want to live,’” says Altman. “There are power spots, certainly. There are sacred mountains. There is a spiritual gravitation that is very real, but I couldn’t articulate what it is.”

Those who try to describe the lure of the landscape invariably say, “It is a spiritual place.” Or, “It speaks to the soul.” Those who have tried to explain it reach to a handful of theories: The Rocky Mountains are the spine of the continent; the vortex of the Four Corners still holds the mysterious power that attracted, then repelled the Anasazi; it is the golden light that reflects off the mountains at sunset that infuses them with pyramid power.

When Altman and others went searching for places to reinvent their generation, they turned to the original occupants of the land, the Taos Pueblo Indians. Altman and Richard Alpert, the former Harvard professor and psychedelic pioneer—among others—found a patch of stunning forested land on the steep slope below the Latir Peaks. Blanca Peak rises dramatically on the northern horizon, a 14,345-foot snowclad sentinel guarding the San Luis Valley in southern Colorado. As Sisnaajinii, it is one of the four sacred mountains of the Navajo, a cornerpost of their world.

With the help of a Taos Pueblo couple, the new pioneers at Lama learned how to dig clay and sand from the ground, mix it with water and form it into building blocks of adobe, the same material used to build the multistoried apartments that still stand at Taos Pueblo.

Beginning in 1967, they built a complex of earthen buildings, and they sought the guidance of Little Joe Gomez, a member of Taos Pueblo who was also a member of the Native American Church, commonly known as the Peyote Church.

Over the years, Lama’s mission has survived varying incarnations. It remains a space for spiritual guests, from Sufi masters and Vedic teachers to Jewish mystics and Native American shamans. Alpert journeyed to India, returning as Ram Dass. Michelle Martin, an early Lama resident, subsequently played a crucial role in founding Bodhi Manda.

Many of those who came to Lama have gone on to other traditions but stayed in New Mexico or close by, because of the same mystical forces that attracted the Lama pioneers. “It’s old people and it’s old people who have preserved something, a tradition,” Altman says. “It’s being close to something that is charged and palpable. It’s deeper than just Buddhism. It’s who remembers the tradition and who remembers the way.”

Altman, who now lives in Santa Fe and sits zazen at the Cerro Gordo Zendo there, found building with adobe and living, literally, inside the earth, helped to focus Lama residents on the interplay of permanence and transience that embodies the wisdom of his Pueblo teachers. “There’s nothing more basic or primitive than making your bricks out of the earth, the whole aesthetic of adobe,” Altman says. “You use the land itself and bring a building up from the earth and when you leave it, it returns to the earth.”

While the land nurtures, its ways are also capricious. A forest fire sweeping through drought-parched stands of ponderosa destroyed most of Lama’s buildings in May 1996, but rebuilding efforts are underway.

The 1980s brought a new wave of dharma students to the region. In the northern reaches of the San Luis Valley, populated mainly by the descendants of Hispanic settlers from northern New Mexico, the Baca Grande Land Grant drew spiritual seekers. An Indian ashram, a Catholic monastery, a Zen center, and several Tibetan practice centers were established, while Lama Karma Dorje, a representative of the Tibetan Kagyu lineage, settled in Santa Fe in 1983 and began building a series of stupas in northern New Mexico, attracting a sangha of Westerners dedicated to Tibetan practice. In Albuquerque, newly arrived immigrants from Thailand, Vietnam, and other parts of Asia began building wats and temples for community worship.

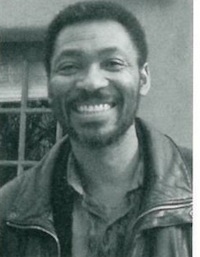

Ralph Steele, a therapist and native of the Sea Islands off the Carolina Coast, came to Santa Fe in 1981 from the West Coast where he had studied with Kalu Rinpoche and Jack Kornfield. “New Mexico is a religious paradise,” says Steele, who arrived to work with a program for the dying and ended up opening his own practice and founding the Santa Fe Vipassana Sangha. He often gives talks on meditation and pain management to non-Buddhist audiences. “You have the Penitentes, you have the Methodists and Sikhs and Hindus and Baptists and Buddhists. Nobody’s pointing any fingers. That’s what holds me here. Even if people don’t believe, they’re willing to listen and question.”

In 1991, the Dalai Lama traveled to Washington, D.C., to plead the case for Tibetan freedom. On the way, he made time for a four-day stay in New Mexico and met with Hopi elders. He emerged with an appreciation of Indian fry bread and an understanding of the similarities between the efforts to preserve Tibetan culture under Chinese rule and Native Americans’ experiences in the United States.

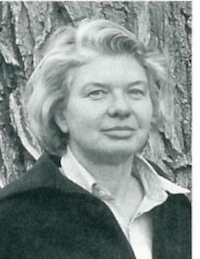

Frances Harwood, an anthropologist, arrived in Santa Fe seven years ago after teaching at Boulder’s Naropa Institute for nineteen years. Harwood and other cultural anthropologists refer to the Rio Grande area as a bio-region, a naturally defined zone where beings are interdependent and where the evolution of human culture—livelihoods, traditions, and spirituality—is driven by the land. Here, that bio-region is organized around the Rio Grande watershed. “What happens when the dharma comes to this area?” Harwood asks. “How will it become native to this place?”

The answer is emerging slowly, in small pieces. Tibetan practitioners build personal shrines from adobe bricks. People place effigies of the Virgin of Guadalupe on their Buddhist altars. In Santa Fe, Joan Halifax, an anthropologist and lay priest ordained by Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, does death and dying work with Native American students and finds room for a dancing kachina figure in a winter solstice ceremony.

An overriding concern for the health of the land pervades Buddhist practices here, emerging as an ecologically-minded, engaged Buddhism. Harwood and Cynthia Jurs, another Buddhist practitioner, are placing consecrated Tibetan vases at the headwaters of the Rio Grande and at its foot, at the Gulf of Mexico, “to help heal the land.” Greg Mello, head of the Los Alamos Study Group, brings his Zen practice to a decade of effort to stop the production of nuclear weapons at Los Alamos National Laboratories.

Meanwhile, New Mexico’s newest dharma center is taking shape. The Albuquerque Zen Center, established in rented quarters in 1989, recently moved into a new zendo and monk’s residence on a nondescript city lot near the University of New Mexico campus. Amid the bustle of a growing city, the connection with the land is retained. The landscaping draws from drought-tolerant native trees and shrubs. Beneath coats of freshly applied stucco and plaster, the walls of the new buildings are made of 5,000 adobe bricks, formed of dirt and straw from the New Mexico earth.

And so, as the land and the cultures it draws put their stamp on the dharma, brick by brick, and breath by breath, Buddhism is becoming native to this place.

Leslie Linthicum, a reporter for the Albuquerque Journal, lives in Alameda, New Mexico.

All historical photographs courtesy of Palace of the Governors, Museum of New Mexico.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.