I’D BEEN SERVING as librarian at the San Francisco Zen Center only a short while in 1974 when I discovered a closet full of banana boxes, all seven of them containing what the poet Philip Whalen termed “dog paperbacks.” A library habitué, Whalen offered to escort me to trade in the books on one sluggish afternoon. His own parlous fortunes through the years had forced him to sell off parts of his personal library, and he knew the used bookstore scene well. Thus we arrived at Holmes Books on Third and Market and unloaded our goods. I waited at the intake counter while a dour clerk pawed through our messy piles. Whalen flitted through the two floors of the place—he could move lightly for a big man when he wished to, and books inspired him. He fetched single volumes to the counter for a while, and then he hit a mother lode: apparently a Harvard scholar had dropped his Buddhist library at Holmes, which contained many valuable reference books and other precious texts. Philip piled armfuls on the counter. Watching the grumpy sorting of our books against the gleeful piling up of theirbooks—those to be bought—it became clear we were going to be on the short end of things. Hard choices would have to be made.

I began to thumb through Robert van Gulik’s Siddham, about the vital role of the Northern Indian Siddham script in the development of East Asian Buddhism. I must have worn a dubious look, because Whalen waltzed over next to me and said, leaving no room for dissent, “Dave, you have got to get that book. That one’s all full of magic. You get that book and we can write our own ticket.”

He took it from my hand and placed it back on the counter as if to say, “That’s settled.”

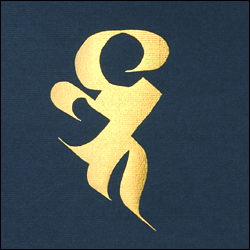

Later at the library, he dropped in for a not uncharacteristic lecture, this time on the general position of Siddham calligraphy in Buddhist tradition. Whalen himself had studied calligraphy at Reed College in the late fifties and early sixties under the seminal teacher Lloyd Reynolds (as I had, twenty years later), and during Whalen’s years in Japan he’d been able to inspect a great many temples and shrines of all lineages. Particularly in Shingon and Tendai temples he’d seen complex diagrammatic mandalas executed completely in Siddham letters. These two schools—sometimes classified by outsiders as “esoteric” Buddhism (another way of saying they incorporate mantra and other Vajrayana or Tantric practice)—used Siddham letters extensively in their rituals. Zen masters brushed Siddham letters as well, but more informally, more for fun. On his way out of the library, Whalen concluded by saying that Zen folk had borrowed all the rituals they had from the Tantrics anyway.

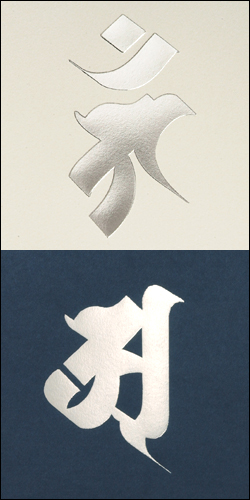

Left alone with Mr. van Gulik’s elegant writing, illustrated with scores of plates, it became clear that this mystic script had played a crucial role in the delivery of Buddhism from India to China, and that it had, since the early eighth century, exerted real power in Japan as well. Arising in India from the extremely ancient root script Brahmi-lipi, Siddham became, together with Devanagari, one of the two leading hands in the classical Gupta period, which ran from the fourth through the seventh centuries C.E. These were the letters used to write down the Buddhist canon for the first time. These were the letters the first Chinese pilgrims saw when they arrived at Nalanda University and other centers of learning, and these were the letters—principally Siddham—they used to copy essential texts before walking back to China with them.

Although preference in India lay solidly with oral transmission over written, an enormous, complex system of sacred writing had grown up there, devoted to placing letters in diagrams, associating them with parts of the body, using them to form representational pictures, or arranging them as protective borders around other artworks. The god Brahma himself was said to have written the letters on leaves of gold. Although not as sacred as pure sound vibrations issuing from the Absolute, letters were still soaked with Brahma’s heavenly essence. Copying them, intoning them, and arranging them in patterns brought one into direct contact with that spiritual essence. Doing it a lot anchored one there.

Letters were seen as an intermediary step between the ineffable majesty of the divine and more elaborated worship—the art and rituals of daily life. The divine rustled itself into form first through sound and then letter, only later taking iconographical shape and story. This was a seamless transition, and letters contained the Brahmic blessings in a very concentrated form. The Tantric tradition particularly is filled with the notion of “seed syllables” (bija) and mantric combinations of letters. Just as the seed of a plant contains the whole plant, so a seed syllable concentrates everything characteristic of a particular enlightened energy—transcendent compassion, for example—which can also be called up in a mantra, or shown in picture, statue, mandala, architecture, dance, parade, or liturgy.

The practice of incorporating single syllables or short combinations of letters into meditation appears to have migrated from Hindu to Buddhist Tantra in India’s Kushan period, in the first through third centuries C.E. Buddhist Tantra differs subtly—though profoundly—from the Hindu in that Buddhists do not subscribe to an origin, a godhead. The undeniable rustlings, rumblings, or thunder of energetic interplay coming into being are not traced to a single source. But the observation that the manifestation of the divine proceeded from subtle to obvious, with letters as an early interim step, presented no problems for the Buddhists.

In a fact of historical coincidence, the Chinese pilgrims arrived in India during the ascendance and sway of Tantric Buddhism there. Thus what they took back included not only the Tripitika, or “three baskets,” of the oldest teachings—the Sutras, Abhidharma, and Vinaya—but the treatises of scholars, siddhas, and yogis flourishing at the time. In the Tantric approach, recitation, visualization, and inscription of seed syllables and mantras play a central role. The applications of Devanagari script included these, but Siddham was more often used, gradually becoming specialized in bija and mantra, so that by the time it entered China, Siddham was a holy syllabary. In China and Japan it was only used for these mystic religious writings.

WHILE MANY ASPECTS of the “Brahma-land” religion remained puzzling to the Chinese, mantras and seed syllables did not. Taoism contained short spells and incantations, the writing of which was felt to be effective magic. As for seed syllables, the idea that a letter or syllable could be in itself the container of complete meaning was not difficult for literate Chinese to grasp. Their writing system arose from pictographs, and to learn the characters was to learn the words, and indeed the language. Correspondingly, to learn and write the seed syllables for deities in a mandala offered a Chinese initiate entrance into that mandala.

Among the many spiritual and cultural pilgrims from Japan who undertook the dangerous and terrifying voyage to China in the late eighth century were two young monks—Kukai (Kobo Daishi) and Saicho (Dengyo Daishi). Both studied Buddhism there, both studied Sanskrit and Siddham calligraphy, Kukai directly with an Indian monk, and both came back to Japan to found schools that promoted the use of magic letters. Although Saicho’s school, Tendai, thoroughly integrated Siddham letters into the liturgical canon, it was Kukai’s Shingon school that raised worship of the letters to remarkable levels. Shingon, after all, means “true word,” so it follows that the spoken and written word stand out. In his bookSacred Calligraphy of the East (1992), John Stevens tells of the characteristic Shingon meditation on the letter A, during which, as part of a longer ritual, the meditator intones and and visualizes the letter—written, of course, in Siddham. (Stevens’s book is, next to van Gulik’s work, the main English-language source for Siddham studies; it provides many splendid examples of the letters, a manual for writing them, a history of the script and its great calligraphers, as well as a good deal of explanation of the esoteric meanings.)

The details of how one uses seed syllables within ritual—their appearance, placement, radiance, duration and dissolution—are transmitted in closely guarded oral instructions, and different Tantric lineages use the syllables in different ways. But the power of the letters, their seed-like concentration of energy, put them on, or above, a level with more elaborated representations, such as paintings, sculptures, or architecture. Stevens reports that, of the four types of mandalas within Japanese Buddhism, those made with letters “are regarded as the most sublime.”

Despite their guarded state, Siddham letters wandered outside the cloister and assumed an independent potency. Perhaps it was the centuries of accumulated insight, faith, meditation, and repetition that invested them with magical feeling; or perhaps it was there inherently. As the great artist and type designer Eric Gill said, “Letters are things, not pictures of things.” In either case, samurai engraved special syllables on sword and helmet, grieving families had them cut into burial steles, pilgrims wore them brushed onto ritual garments, and today one even sees them as a tattoo motif—on the biceps of basketball stars, for example.

Whether the letters will follow the Buddhist trend into digitization remains an open question. One can already read about them and see them on the Internet. But schools that hold the secrets of seed-syllable ritual are the same schools that emphasize a close and sacred relationship to the elements. One might perhaps argue that Internet and digital communication are part of the space element, though it seems likely that when the ancient masters described “mixing mind with space,” they were not referring to wireless routers. If Vajrayana masters of the present day can find ways to transmit the secret teachings digitally, then the seed syllables will come along. We shall see, literally.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.