The quincentenary of Christopher Columbus’ voyage has inspired a welcome re-visioning of that momentous and cataclysmic event. Nowadays, none but the most myopically Eurocentric embrace the myth that Columbus “discovered” America in 1492. That feat, we now know, was accomplished tens of thousands of years ago by small bands of explorers—the ancestors of Native Americans—who crossed over the Bering Strait into the Western hemisphere. In turn, they were followed by a motley crew, some possibly real, some probably not, which included Japanese fishermen landing in Peru around 3000 B.C.E.; Jews finding refuge from Roman persecution during the first century C.E. in what is called today the Tennessee River Valley; the Irish monk Saint Brendan reaching America in a curragh, or skin boat, some time in the sixth century; Leif Eriksson visiting Newfoundland and Nova Scotia circa the year 1000, followed by the Welsh Prince Madoc in the twelfth century. American Buddhists, however, have their own candidate: Hui Shan, a Chinese Buddhist monk who may have reached the western coast of North America nine hundred years before Columbus, thus marking—if not in history then certainly in legend—the earliest beginnings of Buddhism in the New World.

I first heard about the Chinese Buddhist discovery of America from a gentleman scholar, Francis W. Paar of the Oriental Department of the New York Public Library. I went to see him in 1976 while researching a history of Buddhism in America. When I finally found my way to Dr. Paar’s office, he peered at me through his bifocals: “You’ve heard of Fusang, of course?”

Of course I hadn’t. But I wasn’t about to let Dr. Paar know that. I mumbled that I’d heard something about Fusang but would appreciate any light he could shed on the subject. The librarian disappeared into the multilingual stacks of the Oriental collection and within minutes returned bearing a thick leather-bound volume published in 1885 by Edward P.Vining, An Inglorious Columbus: Evidence that Hui Shan and a Party of Buddhist Monks from Afghanistan Discovered America in the Fifth Century A.D.In eight hundred-odd pages Vining recounted the scholarly controversy that had begun in 1761 when M. Joseph De Guignes published Recherches sur les Navigations des Chinois du Cote de l’ Amerique. De Guignes’s book included the translation of a report found in the Chinese imperial archives that depicts a voyage to Fusang by Hui Shan, a Chinese Buddhist monk. De Guignes identified Fusang as North America, in general, and Mexico, in particular. He claimed that the Chinese had therefore “discovered” America nearly one thousand years before Columbus.

Vinning’s book recounted how De Guignes’ theory was first enthusiastically accepted by French and German Orientalists, then subsequently ridiculed by Julius H. Klaproth. Klaproth denied that the Chinese had the navigational skills for the voyage. In addition, he claimed that grapes, mentioned ill the Hui Shan account, were not to be found in America in the fifth century. De Guignes’s theory revived, however, in 1875, when the American folklorist Charles G. Leland published Fusang: The Discovery of America by Chinese Buddhist Priests in the Fifth Century. “If Buddhist priests were really the first men who, within the scope of written history and authentic annals, went from the Old World to the New,” thundered Leland, “it will sooner or later be proved. Nothing can escape history that belongs to it.”

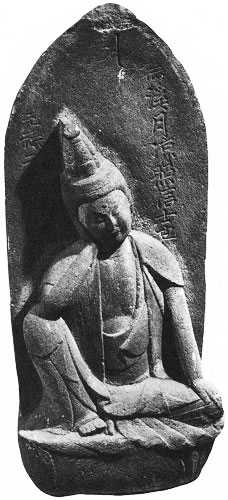

Vining published a number of translations of the original Chinese text and argued that the so-called fusang tree, which according to the Chinese text gave the country its name, was, in fact, the prickly pear cactus. The text goes on to say that the people of Fusang made cloth and paper from the fusang tree; that they did not fight since they had no weapons; that they had carts drawn by horses and deer; raised grapes; lived in adobe houses; had copper but no iron; and that their marriage ceremonies resembled those found in China. The account ends with the statement that “Formerly, this country had no knowledge of the Buddhist religion, but during the Sung dynasty, in the second year of the period called Great Brightness (458 C.E.) five priests from the country of Ki-pin (Kabul) journeyed to that country taking with them their Buddhist religious books and images, and taught the people their Buddhist doctrine and to forsake rude customs and thus reform them.”

Vining supported his argument with numerous plates illustrating strikingly similar Chinese and Mexican design motifs. He also performed wonderful feats of typical nineteenth-century etymological exuberance. In one of his more ingenious examples, for instance, he derived Guatamala from Gautama (the family name of the Buddha) and mala, the Sanskrit word for rosary. As for the mysterious Mayans, Vining suggested that they had adapted their name from that of Queen Maya, the mother of the Buddha.

On the trail of Hui Shan, I soon discovered that compared to later writers, Vining could be considered almost conservative. In Pale Ink (1972), for example, Henrietta Mertz suggested that Point Hueneme in California had received its name because Hui Shan landed there. She noted further that the Huichol Indians, who so resemble the Chinese that the local people refer to them as “Chinois,” perform an ancient dance carrying bowls called sakaimona, a close fit to another of Buddha’s names, Shakyamuni. It was not much of a leap to her next hypothesis. According to Mertz, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl “was kindly, abhorred war, was adverse to cruelty, maintained the most exemplary manners, taught men to cultivate the soil, weave, reduce metals from their ores, and was all that could be considered supreme in a man,” and in her view, this description perfectly fit that of a cultivated Chinese monk such as Hui Shan. Further, she maintained that Hui Shan was probably light-skinned, like Quetzalcoatl, since upper-class Chinese carefully shielded themselves from the sun. Finally, both Hui Shan and Quetzalcoatl appeared and disappeared quite suddenly after teaching people to “forsake rude customs.”

If I read Vining and Mertz correctly, Hui Shan not only discovered America, he may also have introduced the Buddhist teachings there—and all this 900 years before Columbus set sail. It’s an intriguing idea. And yet, I do have to admit that certain serious obstacles prevent replacing Columbus with Hui Shan all too quickly. For one thing, there is that troublesome reference to horses, unknown in the New World until the Spanish brought them there.

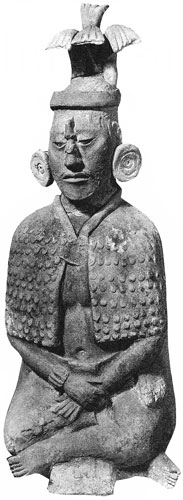

Still. . . Hui Shan could have been describing Peruvian llamas, or very large dogs. And there is that intriguing paper published in 1953 by Gordon Ekholm, which finds “significant parallels” between Hindu-Buddhist and post-classical Mexican art, including the highly stylized lotus, serpent, bowl, and sun. All these symbols have been used by Buddhists, and the fact that they suddenly appeared fully developed in Mexico in the fifth century makes it at least possible that they arrived with Hui Shan and his monks. Then, too, there are those strange circular rocks, with holes cut out of their centers, which divers recently found in the sea off the Palos Verdes Peninsula. Archaeologist William Clewlow says they may be 500 or 1,000 years old and that they may well have been used by the ancient Chinese explorers as anchors. There’s also the story I heard years ago from a retired mining engineer in Oaxaca. He had found a jade Buddha with archaic Chinese characters written on it. When he showed it to a visiting Chinese scholar in Mexico City, the scholar immediately burned incense and performed three prostrations. Then he said that the statue had to be returned to China, and he refused to tell him, or anyone, what the inscription meant.

Like Vining, I could go on. But I think I’ve made my point. We do well not to close our accounts with the past too quickly. The answer to the Fusang mystery may still be waiting—under a jungle-choked Mayan temple in Guatamala, perhaps, or maybe even in some musty old tome deep in the stacks of the Oriental Department of the New York Public Library. Maybe Dr. Paar, though long retired, is even now translating another obscure report on Fusang from the imperial archives. In any case, I have a feeling Hui Shan and Fusang won’t go away. He’s one of our ancestors. He was here all right, along with the dharma, long before any of us ever dreamed we should have any reason to claim him as our own.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.