Science without religion is lame,

religion without science is blind.

—Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955)

With all your science can you tell

how it is, and whence it is

that light comes into the soul?

—Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862)

The time comes when no reflection appears at all. One comes to notice nothing, feel nothing, hear nothing, see nothing . . . But it is not vacant emptiness. Rather it is the purest condition of our existence.

—Katsuki Sekida

A slippery topic, samadhi. A word so many-sided that it poses major semantic problems. It suffers in translation, as will anyone who tries to tag it with but one meaning. Some render it as “concentration,” others as “absorption,” still others as “trance,” “stillness,” “collectiveness,” etc.

The ambiguities date to ancient times. In Sanskrit, samadhi implied a “placing together,” a joining of things in the sense of a union. Successive cultural traditions employed the word in different ways. Six different Chinese characters were used to render the term samadhi, three used to convey the sound and three others to confer meaning.

Drawing on ancient yogic practices, the early Indian Buddhists specified some eight levels along the pathway to what they called samadhi. The levels are difficult to visualize in the abstract, and Zen itself will tend to pay rather little formal notice to such divisions. However, they do describe sequences which are still of general interest to us. For example, the first four stages unfold when the meditator concentrates on some object, some material form, or on some related concept. Initially, thoughts cease, whether they are derived from sensations which had internal or external origins. Then, a sustained, one-pointed rapt attention sweeps in to center on the primary object of concentration. It is accompanied by feelings of rapture and of bliss. Clearly, we are on the path referred to as concentrative meditation.

The word samadhi is currently used in a more restricted sense in Buddhism, where it continues to connote many of the phases, described above, which arise along this general path of concentrative meditation. But in Hinduism generally, the elasticity within the term allows it to be stretched. So that sometimes it also goes on to convey that state of deep concentration in which union or absorption occurs into something closer to the “ultimate” reality.

For our present purposes, samadhi can still imply a bringing together, and a uniting, if we regard such a union as implying the way awareness moves toward, blends into, holds on to, and becomes absorbed into whatever is in its field. To me, samadhi needs to be qualified in order to find its most appropriate use in the Zen context. I reserve the term for complex states of extraordinary absorption. I prefer the general term, absorption. It recommends itself for two reasons: (1) it conveys the way the physical self dissolves when one’s attention is enhanced far beyond its ordinary limits; and (2) it implies becoming totally committed – almost held, it would seem – within one attentional field to the exclusion of others.

Think back to some occasion in ordinary everyday life when a critical event captured your attention. To the angler who fishes with a bobber, one-pointed absorption comes when it plunges out of sight. Only a big fish could yank it this far down! Time evaporates to a standstill during such moments. Well-coordinated movements may go on with rod and reel, but consciousness of the physical self drops far off into the background.

A satisfying activity or hobby can totally engross a person for many minutes or hours. To become playfully lost in a hobby means to submerge oneself so deeply and with such a light touch that no person remains who worries about the project’s success or failure. Then the hobbyist is no longer the captive of time. Life then flows along joyously. Nishitani puts it succinctly: “You are in-samadhi when you are no longer conscious that you are thinking” (italics mine). A Japanese word for this state is yugizammai, “playing samadhi.” It literally means play-absorption. It bears emphasis that any person who engages in play-absorption must still conduct highly efficient playing behavior out in the real world at large. So when you enter “playing samadhi,” you don’t lose that acute vision, hearing, or the other requisite sensate functions – a loss that would, of course, then make it impossible skillfully to land that fish or to perform any other physical activity.

Samadhi implies an awareness that expands outward in the direction of merging with the object concentrated upon. Examples could be the surgeon whose absorption arises out of close volitional control when he copes with a crisis on the operating table; the spectator who can’t help becoming wrapped up in the baseball game when the winning run rounds third base. In such instances, an ongoing external event totally captures that person’s attention. Some would use the term “positive samadhi” for such situations. For our purposes here, it seems better to preserve this same key distinction by introducing a less elastic term. And external absorption seems to be the most appropriate way to describe such moments when the person’s eyes are wide open and seeing, in preference to “external samadhi.”

On the other hand, some absorptions are the result of a deep inward turning. When the state becomes this internalized, the corresponding descriptive term would be internal absorption. The central features of a major internal absorption include (1) no spontaneous thought; (2) an intensified, fixed, internalized awareness; (3) an expansion of especially clear awareness into ambient space; (4) the disappearance of the bodily self; (5) a distinctive closing off of all sight and sound; (6) a deep, blissful serenity; and (7) a marked slowing or cessation of respiration.

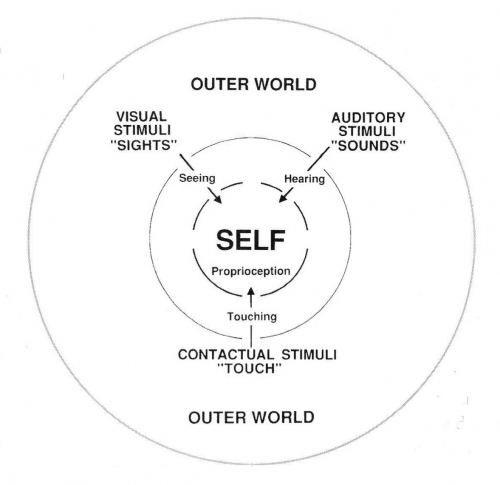

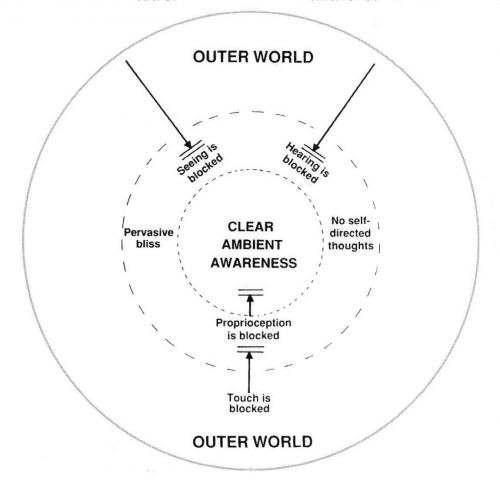

It is a singular state, this sensate loss, combined with an awareness amplified to brilliant intensity. No such mixture is possible to imagine. A person must have been there and returned. In the interim, a pair of diagrams may assist in our discussion. Suppose we begin by adopting the following premise: that the boundary which separates our ordinary self from the outer world is a mental construct. In this case, our conscious mental field containing these self/other relationships will resemble that diagrammed in figure 1. Then, for contrast, the state of internal absorption with sensate loss can be represented schematically by the second diagram, figure 2.

Note how much stops during internal absorption. The person’s mental field lacks sensations of vision, hearing, and touch. Something stops them from entering from the outside world. Absent too are the subtler proprioceptive senses arising from the inside physical self. All that remains is clear awareness expanded to the nth degree throughout a vacuum plenum. The two bars in figure 2 indicate the possibility that synaptic transmission can be blocked in the brain at more than one site.

In the depths of internal absorption, not only does sensate input drop off, but no thoughts engage in any of their usual mental reflections. Later, as the person comes out of this internalized moment, sensate perceptions and affect seem to have been rinsed. “You find yourself full of peace and serenity, equipped with strong mental power and dignity,” wrote Katsuki Sekida in Zen Training: Methods and Philosophy. “You are intellectually alert and clear, emotionally pure and sensitive.”

Involuntary concentration. And the way that it takes over is quite extraordinary. Some authors have concluded that three meditative techniques make it easier to enter into samadhi: (1) becoming totally absorbed in “crawling along” inch by inch from one exhalation to the next; (2) focusing on the lower abdomen (the tanden); and (3) closing the eyes (unorthodox for Zen), so as to facilitate looking inward.

D. T. Suzuki describes what happened to him on the fifth day of one particular sesshin. At the time he had entered samadhi and had become totally absorbed in his koan, Mu. By then, he had lost every artificial separateness which had previously been implied by the phrase “Being conscious of” Mu. Instead, he was “in Mu.” United with his koan, he was in the union of “samadhi.”

Now comes the next phase, a rising up and out from samadhi. It is a sensitive interval, and it can prove critical. In this period of clarity, a sudden stimulus might trigger kensho or satori. To those same persons who, moments before, had been totally absorbed in their koan, being abruptly released from such a focused concentration could become an avenue for reaching the threshold of kensho. Indeed, further to illustrate this point, it is important to note what then happened in D. T. Suzuki’s own circumstance. For it was when a bell awakened him out of this particular samadhi that he went on to experience satori.

In this, and in numerous other examples, one finds a period of samadhi can be a prelude to kensho. Most often, it is a separate episode which precedes awakening by weeks, months, or years. But sometimes, it can precede it by seconds. One can then appreciate how, when these two states do evolve back to back, they could have great impact. A stunned novice might later describe the whole episode as one complex evolving event, oblivious to the fact that the two categories of events had merged as they had fallen one after the other in sequence.

The simpler episodes of samadhi blend themselves into daily life in other ways. As the more advanced meditators sink deeper, to enter and leave successively deeper periods of absorption, they retain for a longer period thereafter their residues of clear awareness and their light, brisk, fluid behaviors. These qualities will then diffuse out to reinforce that quiet awareness which goes on gratefully appreciating each of the wondrous events that make up the day.

♦

Excerpted from Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness(1998) by James H. Austin, M.D., reprinted with permission from The MIT Press.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.