What exactly is blaming? We all know what it’s like to blame the weather, the government, our parents, or the person who rear-ended my car, which is now costing me a pretty penny. And then there’s being enraged at my computer when I’ve made a mistake. These are obvious examples, but blaming can also be very subtle. I remember teasing my mother that I was going to put on her tombstone the words “Who took!” Whenever she misplaced or lost something, she would instantly call out, “Who took…!” to her four children and our father. Even though it had the syntax of a question, it was clearly an accusation. But even if she had asked it as a question, it would have been like the philosopher’s favorite non-question—“When did you stop beating your wife?”—but asked of someone who had never married.

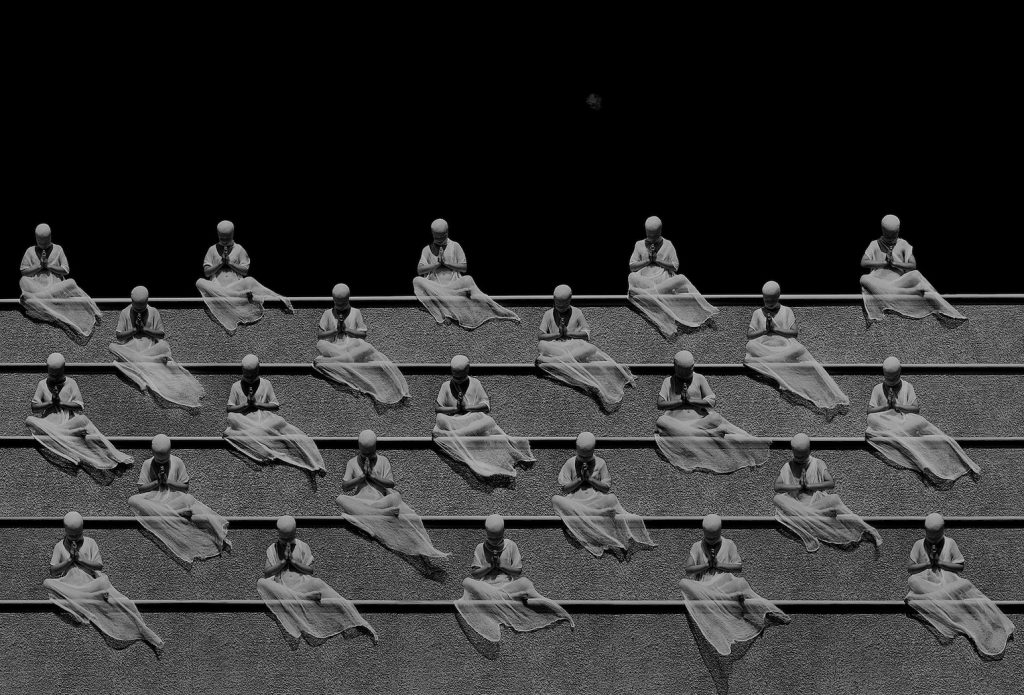

The Bodhidharma version of the precept is this: “The ten dharma worlds are the body and mind. In the sphere of the equal dharma, not making any distinction between oneself and others is called the precept of refraining from elevating oneself and blaming others.” The Eihei Dogen version is “Not elevating oneself and blaming others: buddhas and patriarchs realized the absolute emptiness and realized the great earth. When the great body is manifested, there is neither outside nor inside in the emptiness. When the dharma body is manifested, there is not even a single square inch of soil on the ground.”

The Zen Peacemakers’ version as spoken by the preceptor in the Jukai (receiving the precepts) ceremony, is “Peacemakers, throughout all space and time, have spoken what they perceive to be the truth without guilt or blame. This is the precept of Not Elevating Oneself and Blaming Others. Will you vow to abstain from competing with others or coveting recognition; to give your best effort and accept the results?”

This precept is about there being ultimately no separation between you and me, “the equal dharma,” and “no outside or inside” of the whole, the One Body. Because blame and elevation of oneself make no sense from that point of view, we should describe this precept as non-blaming instead of not-blaming. But before attaining that realization, we work with not blaming. That can just set up more blaming, usually of myself. It’s better to get to know myself in a compassionate and accepting way as a blamer and as one who elevates myself. The more I can do that and the deeper I can go with it, the more this precept will begin to manifest naturally.

The seventh precept has two parts that are deeply connected in ways we often are not aware of. Investigating this connection helps us better understand how we can practice with it.

I learned a lot about blame from a book I used to read with my philosophy of religion students, called The Self In Transformation, written in 1963 by the American philosopher Herbert Fingarette. In it are two connected chapters, one on “blame” and the other on “guilt and responsibility,” in which Fingarette shows us that an important part of our moral development is learning how to blame. We see this in young children and it’s rather cute. A child tattling on a sibling for doing something bad or wrong calls out, “Mommy, Mommy, Johnny’s taking a cookie out of the cookie jar!” There is a certain hysterical tone to it. The enormous energy being expressed is due to the fact that there is in the blamer a desire to perform the very same action and a powerful prohibition against it—and neither is conscious. This happens because the blamer is not mature enough or strong enough to acknowledge his own wish, take the inner condemnation, and experience guilt, which is the next stage in our development. Instead, he or she shoots it out and puts it on someone else.

Needless to say, it isn’t only children who do this. We adults often have very strong judgments about others, expressed with a kind of vehemence. Anti-Semitism, racism, sexism, homophobia, nationalism, practically all the “isms” are examples of this. Homophobia is really the only one correctly named, since it points to an unacknowledged fear in the one making the judgment. There are, however, two very different ways to be opposed to something. To be strongly opposed, say, to abortion as a belief or as a principle by which I live, is one thing, but to get all worked up about it even to the point of killing by bombing abortion centers is something else entirely. In the latter case we see the kind of blame that is the result of an inner unconscious conflict. What is not so obvious is that even being silently and ever-so-slightly judgmental about someone else’s looks, clothing, behavior, or beliefs is also a form of blame. This can include parts of cities and even parts of our own bodies, as Muriel Rukeyser tells us in her poem “Despisals”:

In the human cities, never again to

despise the backside of the city, the ghetto,

or build it again as we build the despised

backside of houses. Look at your own building.

You are the city.Among our secrecies, not to despise our Jews

(that is, ourselves) or our darkness, our blacks,

or in our sexuality wherever it takes us,

and we now know we are productive

too productive, too reproductive

for our present invention — never to despise

the homosexual who goes building anotherwith touch with touch (not to despise any touch)

each like himself, like herself each.

You are this.In the body’s ghetto

never to go despising the asshole

nor the useful shit that is our clean clue

to what we need. Never to despise

the clitoris in her least speech.

Never to despise in myself what I have been taught

to despise. Not to despise the other.

Not to despise the it. To make this relation

with the it : to know that I am it.

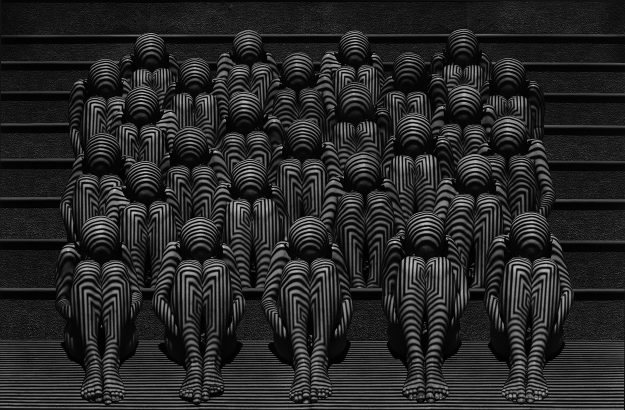

In every case of the kind of blame this precept concerns itself with there is condemnation or rejection of something outside that on the inside I actually am or am afraid I might be. The mechanism of blame is also unconscious. Johnny’s brother isn’t at all in touch with the fact that he is tempted to take a cookie, too. In practicing with this precept—and especially with needing to temper a tendency to be judgmental—it’s good to ask what I am afraid of being or becoming or what I am not tolerating in myself. What I am “ghettoizing” in myself. It’s also good to notice the speed with which blame happens. It’s as if I have to get rid of something so fast that I don’t even have time to look at it.

What does elevating oneself have to do with this? Being engaged in better or worse, right or wrong, sets up a certain kind of hierarchy in which I place myself—not surprisingly—on top. Just notice the simple grammar of elevating myself and putting down another. One action requires the other. There is something else interesting about this elevation. When I’m quick to blame someone, say, for being careless and breaking one of my good dishes, a flash of satisfying anger runs through me. I get a certain kind of rush from it. At that moment I’m innocent, pure, above you, which is to say, I have in some sense elevated myself, even if I am hardly conscious of it and it lasts for only a few seconds. That hit we get by blaming can happen whether there is a very ordinary anger present, a harmless silent judgment about a color someone is wearing, or the splitting off of a whole group of people, as in the case of bigotry, homophobia, sexism, and racism.

There is, of course, just the ordinary sense in which we might ask Who is to blame for letting the dog out? It’s a simple question of finding out whose fault it is. Normally, when I ask that kind of question, I’m not attacking anyone or elevating myself, even if I am quite exasperated by it. But what about serious blame that is seriously deserved? The Holocaust is quite a good example here because it brings out two very different ways of blaming or condemning. One way is self-serving and ultimately in the interest of my own purity. It is an elevation of myself and even gives me a hit of moral superiority. The other way, which may be challenging or even shocking to contemplate for the first time, is a condemnation that includes the thought There but for the grace of God go I, or as the Roman playwright Terence famously put it, “Nothing human is foreign to me.” And the tone of each of these two kinds of blame is completely different. We know this in ourselves and see it in others. This is what the Zen Peacemakers’ version of the precept is addressing when it says that Peacemakers “speak what they perceive to be the truth without guilt or blame.” For example, the Peacemaking way in our ordinary personal relationships, especially if I am hurt, is to speak my truth, to express my feelings: “I feel….” Notice that the grammatically incorrect substitute for this, “I feel that you…,” is blame, pure and simple. Then there is giving feedback, a really good thing to practice. It is very difficult to do in a non-blaming, non-elevating-myself way, which is why some people avoid it altogether. One of the things that makes us pull away, shy away, is the conviction that if I open up and tell the truth, I won’t be safe. Why? I’m afraid to be who I am, to really tell the truth, to be the truth of what I am because it’s unsafe. And you’re the one who makes it unsafe, or so I imagine. So where’s the elevating here? I’m off the hook of truth-telling—and it’s your fault. Giving feedback, criticism, or appropriate blame takes courage.

One of the worst kinds of elevation of the self is playing the victim. There are times when we actually are victims, when actual blame is appropriate, but to take on the identity of a victim and be stuck blaming is something else. Surprisingly, it is actually a subtle form of elevation—I’m not responsible, you are. This is giving up all freedom. I think the reason that remarkable stories of forgiveness take our breath away is that we instantly feel the liberation in the lifting of boundaries, the end of separation, of “inside” and “outside.”

As Fingarette shows us, the next stage in our development, when we are strong enough to take our own blame, is guilt. In this case the inner critic turns inward and condemns our conscious or unconscious wish, which results in a feeling of guilt. We all know what it’s like to walk around with guilt. At some point we’ve all had that experience, and it’s usually because there’s some kind of blaming going on of something in me. But notice, here too there is a separation, only this time in myself.

The next stage in our development from childhood to adulthood and to spiritual maturity takes us out of blaming, through guilt, into responsibility. But it’s responsibility in the deepest sense of the word. Not who’s responsible for . . . It’s responsibility in the sense of Oneness. It’s not quite the same thing but is connected to the way the existentialists talk about responsibility. I’m responsible for my own condition. “Wait, wait,” we say, “aren’t other people responsible for my condition? After all, they conditioned me.” But I will never be free if I stay there, caught in blame of other people for my conditioning or even for my serious injury. Some people have this relationship to their parents or other people in their childhood, but it’s only by assuming responsibility for who we are that we can ever become free and fully compassionate. Fingarette has a surprising example: I’m also responsible for the earthquake that has destroyed my home! The fact is that if I remain a victim, even if I’ve lost everything, there is a certain kind of elevating of myself. If I can assume responsibility, be one with the truth of what’s right here, of what’s happening, then freedom and compassion are possible. “When the great body is manifested,” I know then that I am the earthquake!

None of these phenomena of blaming and elevating oneself would or could occur in the realm of “the equal dharma,” where there is no “distinction between oneself and others,” where “there is no outside or inside.” But even if we have glimpsed or even deeply tasted that realm, we still need what Master Hakuin [1685–1768] calls “the gradual practice of cultivation.” As he puts it,

Even though an enlightening being has the eye to see reality, without entering this gate of cultivation it is impossible to clear away obstructions caused by emotional and intellectual baggage, and therefore impossible to attain to the state of liberation and freedom.

In practicing with this precept, it’s good to keep reminding ourselves, whether we have actually tasted it or not, that there is no “inside” or “outside.” Thich Nhat Hanh’s famous poem “Please Call Me by My True Names” says it all. Not only does he describe the realm of “no distinction between oneself and others” but at the end he also asks to be reminded so he can “wake up” and have the door of his heart left open.

Don’t say that I will depart tomorrow—

even today I am still arriving.Look deeply: every second I am arriving

to be a bud on a Spring branch,

to be a tiny bird, with still-fragile wings,

learning to sing in my new nest,

to be a caterpillar in the heart of a flower,

to be a jewel hiding itself in a stone.I still arrive, in order to laugh and to cry,

to fear and to hope.

The rhythm of my heart is the birth and death

of all that is alive.I am a mayfly metamorphosing

on the surface of the river.

And I am the bird

that swoops down to swallow the mayfly.I am the frog swimming happily

in the clear water of a pond.

And I am the grass-snake

that silently feeds itself on the frog.I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones,

my legs as thin as bamboo sticks.

And I am the arms merchant,

selling deadly weapons to Uganda.I am the twelve-year-old girl,

refugee on a small boat,

who throws herself into the ocean

after being raped by a sea pirate.

And I am the pirate,

my heart not yet capable

of seeing and loving.I am a member of the politburo,

with plenty of power in my hands.

And I am the man who has to pay

his “debt of blood” to my people

dying slowly in a forced-labor camp.My joy is like Spring, so warm

it makes flowers bloom all over the Earth.

My pain is like a river of tears,

so vast it fills the four oceans.Please call me by my true names,

so I can hear all my cries and my laughter at once,

so I can see that my joy and pain are one.Please call me by my true names,

so I can wake up

and the door of my heart

could be left open,

the door of compassion.

This is the precept of Not Elevating Oneself and Blaming Others.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.