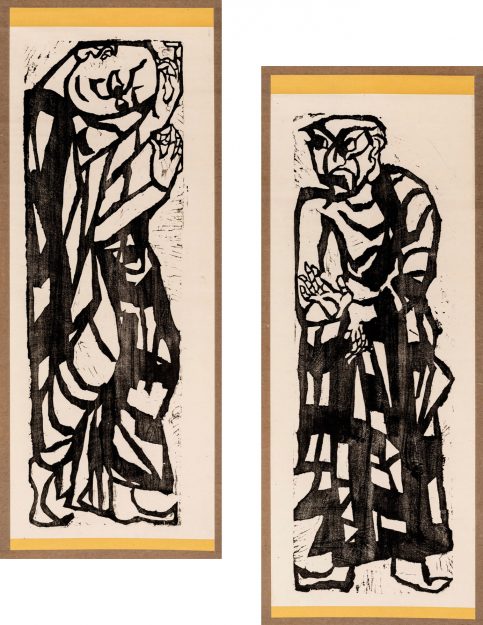

In 1935, Sōetsu Yanagi (1889–1961), philosopher and founding figure of the Japanese folk arts movement, found himself unusually awed by a series of woodblock prints at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum’s annual national art exhibition. The prints were the first breakthrough creation of Shikō Munakata (1903–1975), an aspiring artist then still selling natto (fermented soybeans) by day to make a living. Munakata had several years earlier turned away from oils to the traditional art of woodblock printing, which began with a brief apprenticeship and blossomed into an assiduous, lifelong course of self-study. It was an unlikely object for critical appraisal in the art world in Japan, where the cosmopolitan art scene cast a more serious eye to European styles. However, to Yanagi, who had focused much of his life advocating for the revival of traditional Japanese crafts, or mingei, Munakata’s work offered something singular in both style and intensity to the burgeoning movement. To inspire the young artist, Yanagi turned Munakata’s attention to Buddhism, and specifically the rich artistic and spiritual heritage at Nara, one of Japan’s ancient capitals and home to some of its most treasured Buddhist sculpture. In 1939, after a year and a half of drafting, drawing, and redrawing, Munakata presented a series of woodblock prints at the Japan Folk Art Museum. Titled “The Two Bodhisattvas and the Ten Great Disciples,” they show six facing sets of a well-known series of figures from the Buddha’s retinue, with the addition of the bodhisattvas Manjushri and Samantabhadra. Each print offers a bold stylization of traditional iconographic representations, following the stark, powerful lines of the block to interpret each figure’s role in the Buddha’s hagiography. The arhat Anuruddha’s divine eye points a fiery gaze skyward, and Subhuti, known for his profound understanding of emptiness, casts a knowing downward glance. The images are subtle in their seeming simplicity, playing with direction as much as Buddhist philosophy. The resulting aesthetic of dualities can be seen across the work and Munakata’s life and offers in the very contours of the woodblock a singular view of both Buddhism and art.

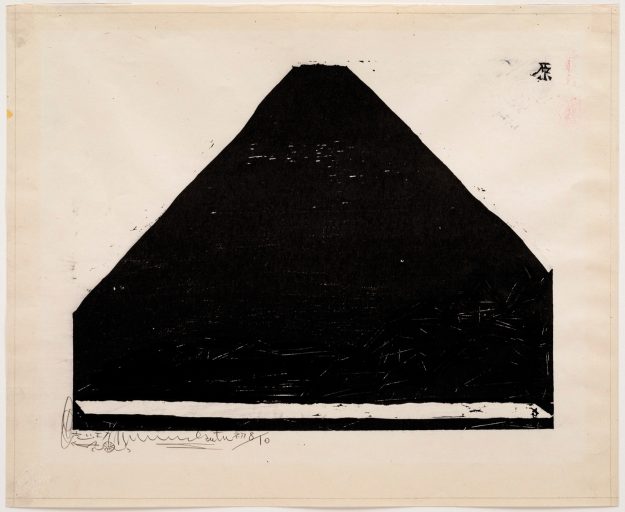

“I listen to the voices within the wood and, through carving, bring them to life.” (1964)

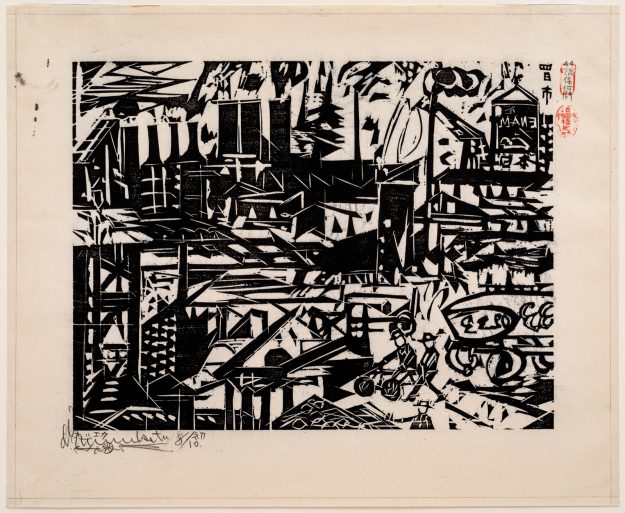

“The darkness of the evening was serious. On the other hand, the daytime was unexpectedly bright. It felt like the whole city was constructed by the machines.” (1964)

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.