Several years ago, at a gathering of American Buddhists of various schools, I introduced myself as a Shin Buddhist to a Zen Buddhist sitting next to me. Smiling, she responded, “So you’re the Christian Buddhist!” I was quite taken aback, but perhaps I shouldn’t have been. It is a view not uncommon among convert Buddhists in the United States, in particular those drawn to meditation traditions such as Vajrayana, vipassana, and of course Zen.

I was about to address my Zen Buddhist neighbor’s misperception, but the program started and I lost my chance. Had I been able, I might have mentioned that, like Zen, Shin Buddhism is rooted in Mahayana scriptures and commentaries, some in Sanskrit dating back to India in the first century of the common era. I might have pointed out that Shin, like other traditions, gives particular emphasis to certain scriptural sources—in this case, those known as the three Pure Land sutras, namely, the Sutra on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life, the Sutra of Contemplation on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life, and the Amitabha Sutra. And I might have said that Shin—again like Zen and other schools—developed from its scriptural roots a distinct character. Shin Buddhism’s distinctiveness centers on the teaching from its founder, Shinran (1173–1263), of a path of naturalness, or jinen, for nonmonastic seekers.

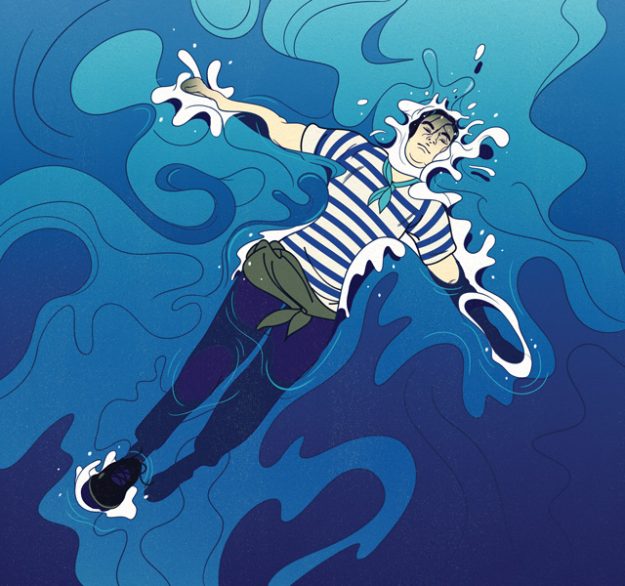

As a child, I heard at my temple in California the Shin way described through a parable of a drowning sailor. Over the years, I have developed this parable into what I call the Seven Phases of a Drowning Sailor. In a manner akin to the oxherding pictures used in Zen, these seven phases can help students understand the course of the Shin Buddhist path from beginning to fruition.

Phase 1

Boarding the Ship

A sailor boards a ship, which departs from the port of a tropical island. After several hours on the high seas, the sailor is on the deck with two of his sailor buddies enjoying the magnificent sunset.

Boarding the ship symbolizes being born as a human being. According to Buddhist tradition, a human birth entails being subject to the suffering, or dukkha, of the cycle of samsaric birth and death. On the occasion of his ordination as a monk, Shinran, who had lost both parents at a young age, captured his acute awareness of the evanescent and unpredictable nature of life and the suffering that comes with it:

If you assume there will be tomorrow

The cherry blossoms may have scattered

In a tempest during the night.

On the other hand, human birth is considered extremely rare and fortunate. It is fortunate because humans, of all those in the realms of the six destinies (heavenly beings, humans, titans, beasts, hungry ghosts, and hellish beings), have the best chance of awakening. The rarity of human birth is likened to the chance that a sea turtle that surfaces only once every hundred years would poke its head exactly through a hole in a piece of wood that happens to be floating in the vast ocean. This outlook today serves to inspire Shin Buddhists, who, prior to taking refuge in the Three Treasures, recite:

On the other hand, human birth is considered extremely rare and fortunate. It is fortunate because humans, of all those in the realms of the six destinies (heavenly beings, humans, titans, beasts, hungry ghosts, and hellish beings), have the best chance of awakening. The rarity of human birth is likened to the chance that a sea turtle that surfaces only once every hundred years would poke its head exactly through a hole in a piece of wood that happens to be floating in the vast ocean. This outlook today serves to inspire Shin Buddhists, who, prior to taking refuge in the Three Treasures, recite:

Hard is it to be born into human life, but now we are living it. . . . If we do not awaken in this life, in which life will we ever be awakened?

Phase 2

Falling Off the Ship

Without warning, the ship tilts violently, and the sailor and his two friends are thrown overboard. No one on the ship has noticed, so the ship continues on its course. The sailor finds himself trying frantically to stay afloat in the extremely choppy and chilly water. He looks around, but his buddies are nowhere to be seen.

Falling off the ship is analogous to our personal encounter with dukkha. Prior to awakening, Prince Siddhartha, the Buddha-to-be, is said to have encountered suffering on his sojourn from his sheltered life within the royal castle, when he saw a decrepit elderly person, a sick person, and a deceased person. Shinran, too, had his life changed by an awareness of suffering, when, in his twenties, he was beset by a gnawing sense of the unsatisfactoriness of life and fear of his own death.

Our human life, of course, presents its shares of joy and fulfillment, symbolized in this story by the sailors marveling at the magnificent sunset. But unexpected upsets and difficulties can appear at any time. The Buddha outlined eight kinds of suffering; in the case of our sailor, suffering takes the form of “encountering a situation that one hates.”

For me personally, my eyes were first opened to life’s suffering as a result of the decision by my American-born parents to leave a comfortable life in Japan to return to America. For a 10-year-old who could not speak any English and was unfamiliar with American culture and custom, the sudden change and the challenges of making a new life in a strange country came as a psychological shock. This was compounded by my parents’ inability to get along. Like the sailor, I felt as though I had been “thrown overboard.”

Phase 3

Swimming by Striving

The sailor realizes he cannot stay in the cold and choppy waters. He then starts to swim toward an island he saw before he fell overboard, but—having lost his sense of direction—he is not completely sure if he is on the right course. He is an able swimmer and manages to swim for about an hour in the hope that he will reach the island. However, as the fading sunlight gives way to darkness and the water begins to feel even icier and more turbulent, the island is still nowhere in sight.

Soon, with his strength exhausted and his lungs gasping for air, the sailor senses that this could be the end. As despair overcomes him, his energy drains from him like sand in an hourglass. He begins to choke on the water slapping his face and can feel his body being dragged under.

Like the sailor beginning to swim with all his might to reach the island, Shinran embarked on the Buddhist path to find a resolution to his suffering. He was ordained a monk in the Tendai school, and he dedicated himself to rigorous practice. An example of one such practice was jogyo zammai (“constantly-walking samadhi”), which required up to 90 days of continuous circumambulation of a statue of Amida Buddha. (Amida is the Japanese, and thus the Shin Buddhist, way of saying Amitabha, the buddha of the Pure Land.) During the circumambulation the practitioners, continually contemplating Amida while reciting his name, barely slept, and when they did they did so standing up, hanging onto a rope suspended from the ceiling of the hall built specifically for this practice. Contrary to a common misperception, monks engaged in Pure Land practices in China and Japan prior to, and often during, Shinran’s time were no less rigorous in their training than, say, Zen practitioners.

Despite his enormous efforts, Shinran, realizing that he was not making any significant progress toward the goal of awakening, began to despair. The more he strove, the more he saw the enormity of his afflictions, or “blind passions.”

In his seminal work, The True Teaching, Practice, and Realization of the Pure Land Way, he wrote:

Oh, how grievous it is that I, ignorant stubble-haired Shinran, am wallowing in the immense ocean of desire and attachments and lost in the vast mountains of fame and advantage.

It was not that Shinran had more afflictions than other monks. Rather, because he was intensely introspective and brutally honest with himself, he acknowledged his shortcomings fully. His honesty was fueled by his great determination to realize awakening in this life.

As one can see from the above confession, Shinran realized that he was woefully steeped in the three poisons of greed, aversion, and ignorance. He came to see that all his efforts were ultimately ego-centered and that they consisted in the belief in what he called “self-power.” Efforts based on ideas of doing good or being good were bound to engender pride and even a sense of superiority. A spiritual practitioner filled with the three poisons while trying to neutralize those very same poisons is, paradoxically, caught up in his or her own effort.

As a result of his inability to overcome his afflictions fully despite making enormous effort to do so, Shinran came to refer to himself as “ordinary and foolish,” a bombu. Shinran’s recognition of his bombu nature emerged from the failure of practice based on self-power. In the parable, the sailor, after swimming with all his might to reach shore, represents the way spiritual practice based on the self’s efforts to overcome the self leads to failure.

Phase 4

Letting Go and Floating

The sailor hears a call from the depths of the ocean: “Let go. Let go of your striving! You’re fine just as you are!” Hearing the call, the sailor ceases his striving, relaxes, and turns over on his back with limbs outstretched as if lying in a backyard hammock on a lazy summer afternoon. Then, to his great surprise, the ocean holds him up and he finds himself floating!

This phase symbolizes the Shin transformative experience called shinjin. Shinjin is at the heart of Shin Buddhist soteriology; it takes place in this life and guarantees Buddhahood upon death. Shinjin is a multivalent term that can mean “realization,” “entrusting,” “faith,” “joy,” and “confidence.” Most Shin writers render it “entrusting heart,” but I prefer “awakening.” Shinran speaks of the “wisdom of shinjin” and tells us that “Great shinjin is none other than buddhanature.” Both wisdom and buddhanature are revealed through the personal experience of awakening.

The content of shinjin involves awakening to two Buddhist principles, namely, emptiness and interconnectedness. Shinran, however, expressed them in distinctively Pure Land terms: emptiness as “the depth of his bombu nature” and interconnectedness as “being embraced in Amida’s compassion.” He expresses in deeply personal and mythic language these two foundational teachings of Mahayana Buddhism.

For Shinran, shinjin was not a simple belief in Amida as a divine being. It entailed wisdom and insight. It is, therefore, not surprising that Shinran equated shinjin with the first stage of liberation, stream-enterer, found in early Buddhist texts and with the first of Mahayana Buddhism’s ten stages, or bhumis, on the bodhisattva’s path, the stage of joy. Although those who reach these stages have yet to overcome the deeper layers of mental afflictions, they have achieved an essential initial level of awakening.

With greater room in his heart, the sailor desires to help his buddies by sharing with them his experience of letting go.

Going back to our parable, in Shin Buddhism the ocean is none other than Amida Buddha. Amida is often thought of as the foundation that supports us from underneath, the sides and behind. Shinran, for example, speaks of Amida as “the immense ocean into which all the rivers of sentient beings flow.” Amida constitutes the foundational reality that has been there all along, underneath and around us. We simply fail to notice it because of how we strive. We get too caught up in our effort to reach the island solely on our own power.

Amida is ultimately not a divine being dwelling in an unfathomably distant paradise. Amida’s essence is ineffable and beyond form. Amida is, therefore, the provisional manifestation of ultimate reality, which is expressed in such mainstream Mahayana Buddhist terms as “suchness” (tathata) and “dharma-body” (dharmakaya). Shinran also used a term considered unique to him, jinen honi, which I render “suchness of naturalness.” It was this suchness of naturalness that Shinran had awakened to. Just as the sailor let go of striving and realized that the ocean embraced and uplifted him, with shinjin, one lets go of egoic self-power and awakens to Amida’s workings, or other-power.

Phase 5

Joy

The ocean holds him up without any effort on his part, and the sailor is thus overjoyed. Now the water feels warm and the waves have stilled. The ocean that was about to drag him under and drown him now caresses him. Knowing that he is all right, the sailor is filled with gratitude and happiness.

The sailor was about to drown. When he began to go under, he was struck with a sense of utter terror. Then, when he relaxed and let go, he found himself floating. How could he not be overjoyed?

Further, his sense of joy is accompanied by the realization that he was fine all along. He just didn’t know it. The ocean has not changed at all. But because he stopped striving so hard, the sailor’s relationship with the ocean was transformed. The sea changed from being a dangerous and frightening enemy to being a friend who embraced and supported him.

Shinran’s encounter with the teachings of Honen (1133–1212) revealed a path of naturalness wherein all beings are embraced, even with their blind passions intact. Shinran expressed the profound joy that came upon him with this awakening:

Oh, how happy I am! My mind is firmly planted in the ground of Universal Vow (Amida’s workings) and my thoughts flow in the Inconceivable Dharma Ocean.

Phase 6

Swimming with Ease and Assurance

The sailor begins to swim again toward the island, but with one important difference. He now trusts the ocean as he would a caring and protecting loved one. He knows that whenever he becomes tired, he can let go, and the ocean will support him just as he is.

Continuing to swim with ease and assurance symbolizes living a life rooted in shinjin. As the sailor now feels safe in the arms of the embracing sea, he finds more room in his heart to make use of his nautical knowledge. He studies the positions of the stars and the moon and the direction of the wind. He then determines with greater certainty the location of the island and swims confidently and energetically toward it. Furthermore, because he is less caught up with concern for his own survival, he is better able to look around him for his sailor buddies. Now, with greater room in his heart, he desires to help by sharing with them his experience of letting go.

In 1207, Honen and some of his disciples, including Shinran, were exiled from the capital city of Kyoto by the emperor, mainly in response to the charges of the monastic establishment of the time. They claimed that Honen’s emphasis on the single practice of nembutsu (recitation of Amida’s name, “Namo Amida Butsu”) appeared to them to ignore or deny the usefulness of essential aspects of Mahayana Buddhism, such as the generating of the aspiration for awakening (bodhicitta). They also charged that because Honen taught that all were equally embraced by Amida’s compassion, the categorical difference between monk and layperson was undermined. Following exile and being defrocked, Shinran led a life of naturalness and ordinariness, which included getting married and having children.

At the same time, he continued to practice and teach others with the dedication of a monk, which led him to describe himself as “neither monk nor layman” (hiso hizoku). In my view, Shinran’s life of naturalness transcended and encompassed both those categories. Even when he was pardoned and allowed to return to the familiarity and comfort of Kyoto, he headed to a region north of Tokyo, a hinterland with far less Buddhist presence. After some twenty years, he returned to Kyoto. All this time, and until his death at ninety, he devoted himself to the propagation and practice of his Pure Land teaching. He taught those of high and low status, rich and poor, priests and laypersons, those educated and those not. He taught those who were generally considered unfit for Buddhist practice, including women, fishermen, samurai, and even criminals. For Shinran, no one was beyond the reach of Amida’s workings.

Phase 7

Liberation

Upon reaching the island, the sailor now takes out a small boat and sets out to locate and help the others who fell overboard.

Reaching the island symbolizes the attainment of full awakening—that is, buddhahood—or birth in the Pure Land at the end of life. Actually, for Shinran, the two are virtually the same, because he taught that when a person of shinjin dies, he or she is born in the Pure Land and immediately attains buddhahood. This teaching that one does not spend time in the Pure Land cultivating one’s practice toward full awakening is a radical departure from the teachings of earlier Pure Land teachings in India and China. What was key for Shinran was the realization of shinjin awakening in this life. But the path does not end there. With the attainment of complete awakening, in keeping with Mahayana cosmology and the bodhisattva spirit of benefiting all beings, one returns freely to the unenlightened realms to assist in the ongoing effort to liberate others.

I imagine returning as a caring first-grade teacher, a bird with melodious chirps, an enlightened politician, a soothing breeze, dedicated in each birth to assisting others in awakening.

Shinran does not discuss the exact manner in which one returns, so I, as a Shin Buddhist, can take the liberty to imagine all the possible forms I would like to take. After all, as Buddhas we are endowed with any and all skillful means! I imagine returning as a caring first-grade teacher, a bird with melodious chirps, an enlightened politician, a soothing breeze, and a Buddhist nun, dedicated in each birth to contributing in some small ways to assisting others in awakening.

In closing, it is my earnest hope that my Zen dharma sister mentioned at the beginning may read this essay and change her mind, agreeing that Shin Buddhists are not Christian Buddhists after all; I then will exclaim with joy, “Oh my God, that’s great!

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.