In early 2017, Nikko Odiseos, president of Shambhala Publications, expressed concern about the transmission of Buddhism to the West. His primary consideration, as posted on Lama Dechen Yeshe Wangmo’s online resource Vajrayana World, had to do with “how we read, what we read, and who is reading—or not.”

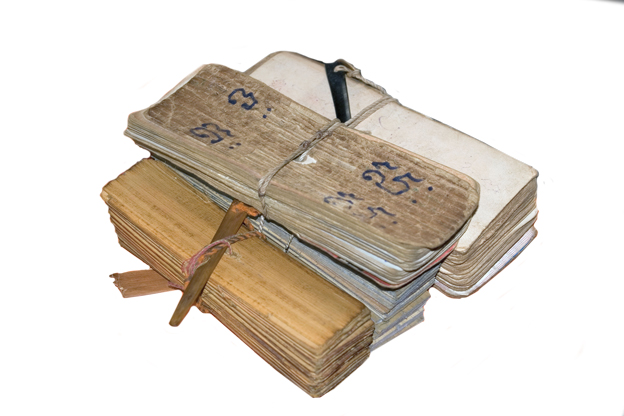

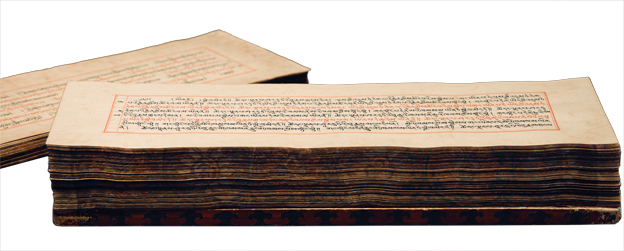

Every year, dharma students in the West gain access to a trove of newly released books about Buddhism. These books—connecting dharma to relationships, the workplace, and child-rearing, or interpreting Buddhism through the lens of neuroscience, psychology, and physics—attempt to adapt Buddhist teachings in ways that make them relevant to modern life. Such adaptation is not unique to today, nor is it unique to the West; the desire for guidance in the affairs of contemporary life has pervaded the history of Buddhist expansion from one culture to another. This spiritual adjustment has been possible, however, because cultural interpretations of the dharma have been grounded in Buddhism’s foundational texts.

Historically the domain of monastics and religious professionals, the in-depth study of sutras, koans, and influential treatises has always been a stronghold of dharma practice and transmission. But in modern Western culture, where monastic ordination is rare and the practice of meditation is for many the sine qua non of what it means to be “Buddhist,” is there even much interest in what the traditions’ foundational texts have to say? Translators’ efforts have made such sources increasingly available to English-speaking students, but according to the president of Shambhala Publications, sales of these works are low—and not growing.

Last fall, Tricycle spoke with Nikko Odiseos; Myotai Bonnie Treace, Sensei, former vice abbess at Zen Mountain Monastery and founder of the Hermitage Heart Zen community in Asheville, North Carolina; Reverend Marvin Harada, Jodo Shinshu Buddhist minister at the Orange County Buddhist Church in Anaheim, California; and Daniel Aitken, CEO and publisher of Wisdom Publications, to understand what the Buddhist schools’ foundational texts are, why they matter in the context of cross-cultural dharma transmission, and how they can be a vital part of the Buddhist experience in modern Western settings.

Let’s start by defining terms. What do we mean by “foundational”?

Daniel Aitken (DA): There are a few ways to think about foundational texts. The first is to think of them as a tradition’s authoritative voice on an important philosophical idea or central practice. In the Tibetan tradition, for example, certain Indian texts form the underlying basis for a deeply established curriculum of study, known as the five great subjects, that covers topics ranging from rules of discipline to valid cognition and the characteristics of emptiness. Such a text would be Nagarjuna’s Root Verses on the Middle Way, for example, or Chandrakirti’s commentary on Nagarjuna’s text. Another way to think about foundational texts is that they provide a prerequisite knowledge for the study of advanced texts. Just like we need a certain level of study before we jump into a class on quantum physics, there are books that prepare us for advanced subjects. Again, in the Tibetan tradition an example would be the Seventh Karmapa’s text on logic and epistemology. Such texts belong to a different set than a work like Nagarjuna’s Root Verses but can be considered equally foundational. Or a text might be considered foundational because the Buddha or the founder of a lineage taught it.

Nikko Odiseos (NO): The answer to this varies a lot not only among traditions but also among specific lineages in those traditions. For someone who is practicing from the early, South Asian schools that look to the Pali canon as authoritative, engaging the suttas is crucial. Rather than just hearing what the eightfold path is as a list, the reader gets a much fuller, more practical, human sense of its components through reading the literature. Even for nonmonastics, the Abhidharma’s collection of texts that map the activity of consciousness and the Vinaya [monastic rules] collections are also important, but they tend to be less accessible.

Practitioners from East Asian traditions rely on such texts as the Diamond Sutra, Lankavatara Sutra, and Flower Ornament Sutra, as well as the later Chan and Zen literature. Tibetan lineages, which in practice tend to favor commentaries and later expositions over sutras and tantras, emphasize works such as Patrul Rinpoche’s Words of My Perfect Teacher or Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim chenmo [“The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment”].

But really, compiling lists of foundational texts for each tradition or even subtradition is hard, because there is so much variation.

Related: Reflections of the Flowerbank World

Reverend Marvin Harada (RMH): The primary texts in Shin Buddhism are the three Pure Land sutras, which were selected out of all the sutras in the 12th century by Honen Shonin, the teacher of Shinran Shonin, who was the founder of our school. The main one is the Larger Sutra of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life. The second one is the Meditation Sutra, and the third one is the Amida Sutra. I find that many Shin Buddhists focus on studying Shinran’s opus The True Teaching, Practice, and Realization of the Pure Land Way, but in fact that text is all based on his study of the Larger Sutra, so to me it’s more important that we study the Larger Sutra.

How important is it that contemporary dharma practitioners engage with these kinds of texts? Traditionally, deep study has been mainly limited to monastic environments. In the West, there is a much larger lay population.

Myotai Bonnie Treace, Sensei (MBT): Right—so in addition to the many different strands of traditions, there are also several kinds of individuals within a tradition. There is the religious professional—a category that is understood differently in different lineages, schools, and orders—and there are also lay practitioners at varying levels of seriousness.

In the early eighties I worked with John Daido Loori Roshi on developing the curriculum now taught at Zen Mountain Monastery, which emphasizes both deep and broad exposure: the recorded sayings of masters, the koan collections, and the monastic codes, as well as the interpretive literature that goes beyond the fundamental genres, such as the capping verses for the kirigami [commentaries on esoteric medieval Soto Zen verses given during dharma transmission]. We also study the sutras, in part because so many of the koans refer to them. The curriculum includes classes, workshops, intensives, and individual study over a course of ten to fifteen years. We don’t have that structure at Hermitage Heart; I send students who have that level of dedication to the monastery.

Broadly speaking, I think that’s where we need to respect the role of the monastic institutions as a kind of university; their continuity, steadiness, and size means they have the educational resources that can’t really be replicated by small centers.

“‘It’s not necessarily the volumes of books you read, but how carefully you study even one book.’”

DA: If we’re talking about a serious Buddhist practitioner who is committed to progress on the path, then I think a certain amount of foundational text study is required. But it’s also not just what you study, but how—how your study is structured, and the order in which ideas are presented to you. I think that’s super important. One of my teachers, a Tibetan, once said, “You shouldn’t study dharma like a yak eats grass—a little bit over here, a little bit over there.”

NO: I think it’s a question of quality versus quantity. In other words, the monastic model should still very much be applied here—that’s the sense of slow, deep study of a particular text until you “get” it. Reading a book from front to back and then moving on to the next one is not something that I think most—or any—of the traditions would encourage.

Then again, there is the enormous problem of not having any institutions that support an evolving Buddhist culture and instead trying to adapt our existing ones, like academic universities, to this moving target. I cannot think of a place where Buddhism successfully gained a foothold without institutional support, which tends to mean monastic support, often but not always with state sponsorship. In the West there is no state sponsorship; while Western monastics permeate many practice communities and centers of study, there is not yet—nor does it seem we are likely to see—real institutional support for the wider, highly diverse, and mostly lay world of Western Buddhist practitioners. Academia has had something of a role in filling this vacuum, but the scholars tend to look at Buddhism from the outside with a critical eye and with an impetus to say something innovative or new about something very old, so that by definition they do not fill many of the functions that more traditional supportive institutions have served.

RMH: One teacher said to me, “It’s not necessarily the volumes of books you read, but how carefully you study even one book.” I took this advice in my approach to the Larger Sutra study class: we go character by character, line by line. We only get through maybe a few lines in each class meeting, with the help of a commentary from the 1950s by the Shin Buddhist minister Reverend Haya Akegarasu. We’ve been going at it like that for ten years now. It’s a small class, maybe 10 or 12 individuals, who I’d say are the more devout members that are seen by others in the community as role models.

NO: Recently I was talking with a khenpo [a Tibetan Buddhist scholar] who came from Larung Gar in eastern Tibet, one of the largest Buddhist institutions in the world. He outlined 13 core texts that are still used in a lot of the monastic colleges in Tibet, particularly those in the Nyingma tradition. A lot of these texts we actually have translated into English now. I asked, “So what’s the order you teach them in?” And he said, “There’s no way you can just write down what this curriculum is and simply reproduce it.” This is because the method is so different from just having a list of books that you go through and check off. It’s a much more immersive, engaged experience.

They do things in a way that’s similar to what Rev. Harada was describing—they take one particular text, like The Way of the Bodhisattva or Words of My Perfect Teacher, and they reteach it year after year. And after each daily or weekly teaching, those attending break into groups and talk about the text and review it. And when they return to it the following year, they’ve put it into practice, which means that when they hear it again, they’re hearing it in a new way. It’s a very different model from what we have here.

This brings up in particular the role that publishers play. Publishers collect material and make it available in the general marketplace, but should they collaborate with teachers to structure how readers approach what is published?

DA: I’d say that’s the next move. We’ve gone from whatever’s on the shelf at Barnes and Noble to having everything available at once on Amazon. There are two problems that come along with that change: First, how can I find the book I want? And second, what should I read next? Those two things are the next big challenges for publishers—guiding readers to help them find the text their teacher is directing them to read and study, and helping them wade through all of the material and decide what to read and study next. I think that’s the role of the Buddhist publisher now—advised, obviously, by lineage teachers.

NO: It’s tricky. A lot of that is the job of the teachers and the sanghas themselves: to define the order and structure. There are things that we can do—we have lots of readers’ guides up on our site, and interviews with translators and things like that—but I don’t see us as arbiters of deciding what to push. Our goal is to make texts available, so that when people do turn to them or do become interested in them, they’re there. That said, we don’t do much liturgical material—we leave that to the sanghas.

We should also recognize that each tradition has its own way of developing a student’s relationship to foundational texts. I’m thinking of the Tibetan tradition, for instance, where a student’s relationship with their root teacher has as much significance as, if not more significance than, their connection to the historical Buddha. In that context, the way authority is given to certain texts and teachings is going to be very different from, say, how this takes place in Theravada Buddhism.

NO: I’ve definitely seen lamas in the West who were pushing people more on the practice side and discouraging them from reading some of these foundational texts. For that particular sangha or student, that advice is primary, because it comes from their teacher. If someone is particularly prone to getting hung up on logic and stuff like that, a teacher who has spent time with that student and really knows them might guide them in a different direction. It’s all very contextual.

MBT: The relationship between practice and study can work both ways. I remember that many years ago sutra and koan study were very limited because of what was translated and available. You would receive a koan, but parts of it weren’t translated, so you could go off in a direction with it that was misguided because you didn’t quite understand what the question was, what the koan itself was asking. That has changed now, and that’s significant.

There are times when you say to a student, “No reading—nothing but this koan until another word is given.” You ask them not to relieve any of that pressure, and that’s it. But there are also times when there is no issue with a student’s having understanding as well as insight.

Do you think that the study of foundational texts is necessary for Buddhism’s full transmission to the West?

NO: I do think that whatever constitutes a successful transmission of Buddhism on the level of society and not of an individual will involve deep engagement and absorption in the textual traditions that have come down to us over the centuries. Does every person who wants to be a serious practitioner need to do it? I don’t think so. But from the standpoint of establishing a settled American or Western Buddhism, I do think it’s absolutely important.

RMH: Yes, I think it’s very important. At most of our temples, the ministers are trying to conduct some kind of a study class for their members. I myself mentioned the study group I started for the Larger Sutra, which I did for very selfish reasons—I wanted to study the text in more depth myself and I thought teaching a class would force me to study since I’d need to prepare the materials.

Of course, not everyone can go into that kind of in-depth study, but we need some individuals, both laypeople and teachers, to do so. Then they can share their insights from those texts by writing their own secondary sources.

Speaking of secondary sources, how do you see the relationship between the study of foundational texts and that of more popular books from modern teachers—books that are typically geared not toward traditional Buddhist thought but rather toward the immediate concerns of practitioners?

RMH: I think the popular books are just as important as the foundational texts. A popular or secondary sourcebook can introduce the depth and breadth of a foundational text teaching, and the average person who has not studied that text can be inspired or motivated to study it as a result. Without such books, the important Buddhist texts might remain only on the shelves of Buddhist libraries, never being studied or read.

NO: Contemporary presentations are particularly important, as they are the place where many people begin. There are many great examples of contemporary teachers, people who are invariably well trained in a specific tradition, who write powerful books that reach beyond the confines of that tradition and the surrounding culture to speak directly to our own experience. With the best of these kinds of works, a reader can deeply internalize the meaning through reading, reflecting, rereading, practicing, and so on, and this can have a profound impact on them, whether they self-identify as Buddhist or not.

But I do think there needs to be some caution. The Buddha is said to have given 84,000 teachings or paths. Of course, the precision of the number is not important; rather, the point is that there are teachings and techniques to address every neurosis, negative thought or emotion, and spiritual longing. So it’s all there; it’s not incomplete. How the mind works has not changed, so watering Buddhism down, cherry-picking it, or mixing it is a slippery slope to misinterpretation and ineffectiveness. The language can change or the metaphors and examples can shift to meet us where we are. With our iPhone-gripping hands, 24-hour news, Tinder-born relationships, and world of instant gratification, we may need to find new ways to make the points resonate with a new generation. But the essence of the teachings should remain consistent.

The best of the contemporary presentations will, hopefully, eventually lead people to the foundational texts and their early and more recent commentaries. We as a publisher feel a responsibility to make sure that a Buddhist book project is not straying from the core views and practices of any of the lived traditions of Buddhism, as diverse as they are.

What about the challenges faced in transmitting the foundations of Buddhist thought so that they address Western currents of knowledge such as the academic study of history, pluralistic understanding, and natural science?

RMH: To me, there isn’t a challenge in terms of Buddhism and the study of history, science, and so on. The teachings in the sutras are “timeless” teachings, but the expressions and words used in the sutras reflect a period of time and culture. We don’t take the expressions and language of the sutras literally. One of the standard Buddhist explanations for the length of one kalpa is the time it takes for a heavenly maiden to wear down a rock that is one mile tall, one mile wide, and one mile long. The maiden descends from the heavens once every three years and brushes her gown on the rock: one kalpa is the length of time it takes for her to wear the rock down to nothing. Kind of blows the mind, right? That is why we take this definition not literally but metaphorically, meaning eons and eons of time.

DA: The Dalai Lama’s approach to this question is admirable. He has said that if empirical observation contradicts a particular Buddhist account of the physical world, then the Buddhist position should be dropped. But perhaps the biggest challenge in transmitting the depth of Buddhist thought to the West is the lack of questioning concerning the assumptions that ground our scientific observations, such as physicalism—the proposition that everything is physical or follows from the physical. I believe that Buddhist texts have a lot to contribute to philosophical conversations about these kinds of fundamental assumptions.

“How the mind works has not changed, so watering Buddhism down, cherry-picking it, or mixing it is a slippery slope to misinterpretation and ineffectiveness.”

NO: The biggest challenge is that the medium can easily become the message, so that we miss out on what was trying to be articulated in the first place. Why do Buddhists always need to validate Buddhism from the points of view of science or psychology? We do this all the time, over and over. Are we too insecure about our own logic and views of reality? I can see the value in drawing parallels, but having to justify Buddhist views on the basis of these traditions doesn’t seem particularly helpful. And science, of course, has innumerable useful applications, but it is not really offering anything new in terms of helping practice. Close reading in a particular genre—for example, the Pali or Mahayana Abhidharma literature, followed by putting its insights into practice through repeated reflection and meditation—will give a practitioner a more solid understanding of the dharma than countless brain wave measurements can provide.

That said, one benefit of the pluralistic and scholarly approach is that prejudices within Buddhism are getting worn down. For example, there is an orthodox view in many Southeast Asian countries that while Theravada is based on the authentic teachings of the Buddha, Mahayana is some kind of later invention. But this idea wears thin when one sees the historical evidence, since we now know that many Mahayana texts appeared at the same time as many of those in the Pali tradition. Common characterizations of the Theravada tradition, such as the claim that its followers seek simply to be arhants [individually liberated beings] for themselves or that its teachings are primarily about suppressing thoughts and feelings, are also breaking down in light of newer textual and anthropological research.

As is true in any realm of knowledge, it takes considerable time and effort to engage Buddhism’s long conversation in a full and rich way. Academics can do this in their way; religious professionals can do this in their way. But most contemporary practicing Buddhists—including readers of Tricycle or books from Shambhala or Wisdom Publications—are neither of these. How are those who are, as Shinran once said, “neither monk nor layman” to stake out a place and find a model for participating in Buddhism’s vibrant intellectual tradition?

DA: I don’t believe vocation is the primary barrier to a deeper participation in Buddhism’s intellectual tradition. I think it is important to view vocation not as an obstacle but as a means to deepen one’s practice. Every situation we face in life presents an opportunity to put the principles of Buddhist thought into action in a way that benefits ourselves, our families, and our communities. Learning through the experiences of daily life is a powerful way to deepen our engagement with Buddhist thought. I have, however, observed that in many cases the ability to delve deeply into Buddhism’s intellectual tradition relies upon fluency in the primary language of that tradition. Obviously not everyone has the time to learn new languages, so we need more translators, translations, and modern voices to express the Buddha’s insights in a way that speaks to contemporary life.

Related: Found in Translation

RMH: Digging into the depth of the teachings held in the sutras is and should be a multifaceted approach. Academics can share their understanding of the text, and religious professionals and laypeople theirs. We can all mutually learn from one another.

In my study class, quite frequently a layperson will share a profound insight or understanding of a passage that neither I nor any scholar of the text has presented before. I am constantly learning from the dialogues I have in my class with those who are reading and studying the text with me. I utilize the translations of Buddhist scholars and academics in preparing for the class, but we all study the text together. In that sense, I’d say that we are “neither monk nor layman.”

Along those lines, the great D. T. Suzuki late in his life wrote about the Shin Buddhist devotees called myokonin [lit., “wonderful person”], who were in many cases illiterate laypeople with very little education but who had a deep spiritual understanding of the Shin Buddhist tradition. But those myokonin came to their deep understanding by listening to scholar priests who had studied the text and were sharing it in their dharma talks. They never read the texts themselves.

NO: I think there is a side of Buddhism we tend not to talk about, as Buddhism in the West is very focused on practice, such as not following thoughts in order to allow insight to develop. But for many people, practicing wholeheartedly involves a long process of learning how to think. Many teachers intentionally present the teachings to establish a clear view and understanding through which we see the lessons of the Buddha being demonstrated by each and every experience. That gives us more confidence to go deeper, and the foundational texts are there for us to support and augment this.

As a final thought, I would like to share something from my personal experience that may not apply to everyone, but that I suspect many will share. There is something so enriching and joyful about slowing down and going back to some of the basics, to reading and rereading the original texts and commentaries with fresh eyes. I was reading the recent release of a 19th-century multivolume work from Tibet, The Complete Nyingma Tradition. This particular volume about philosophical systems included a presentation of what views are considered non-Buddhist, “mundane approaches.” A few days later I was reading from the Samannaphala Sutta in the Pali canon, where the Buddha and King Ajatasattu are questioning each other about the fruits of the Buddhist path and the latter describes his talks with a variety of teachers who in many ways represent the same non-Buddhist views discussed in the Tibetan text. Something about this reading—with its story setting of a still, clear moonlit night—brought the whole thing alive in an amazing way and made me further appreciate the more expository presentation I had read earlier. Both passages brought into clear focus for me many of the issues that arise in the current conversations between scientists, scholars, Buddhist traditionalists, Buddhist modernists, people of other faiths, and those just trying to get a handle on how the world works. Both sources are examples of how these foundational texts are absolutely relevant and meaningful to us here and now. Read them: you will see.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.