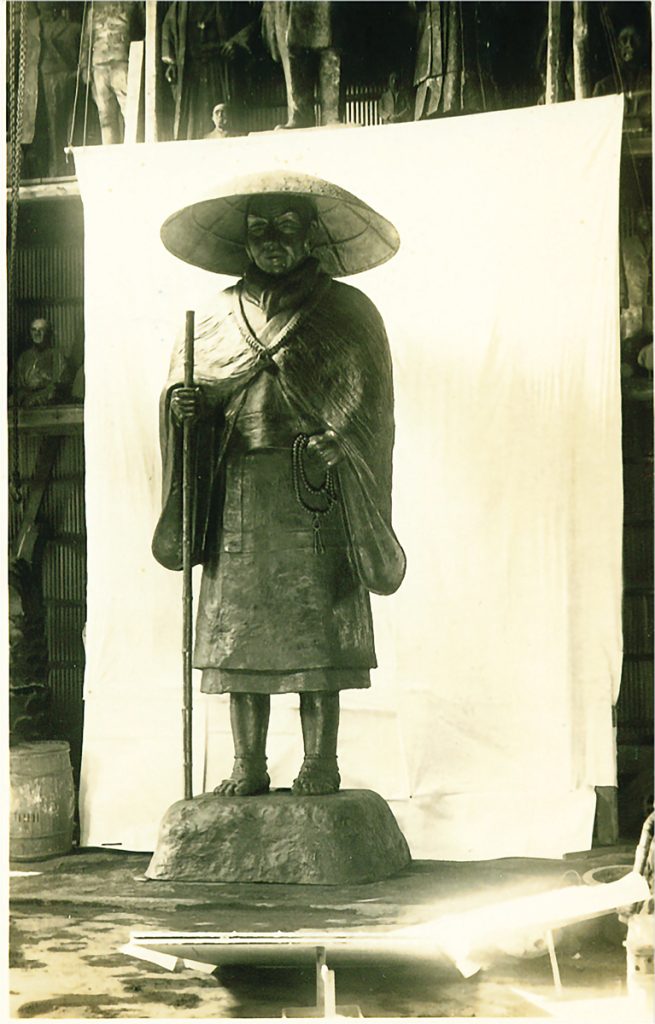

In Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Shunryu Suzuki told his North American convert students that their practice path would be that of “neither layman nor monk,” a quasi-monastic style of practice without the traditional support of a lay congregation or wealthy sustaining patrons. Even while pursuing Buddhist practice, students had to meet the exigencies of lay life: maintaining jobs, friendships, family commitments, and the rest. This “center-based” model is something that nearly every practice community has been working on ever since. What is not so well known is that Suzuki’s model of “neither layman nor monk” comes from another, earlier master: Shinran (1173–1262), one of Japanese Buddhism’s most celebrated figures.

Shinran was the founder of Jodo Shinshu, or Shin Buddhism, as it is known in English—the Japanese stream of the Pure Land tradition that originated in India and came to encompass one of the largest bodies of practice in East Asia. Shin Buddhism first appeared in the West in the late 19th century, and the teacher, writer, and translator D. T. Suzuki, best known for his works on Zen, wrote extensively in the 1960s about the Shin tradition; but its practices, including chanting the name of Amida Buddha, are only now becoming widely recognized in North America among convert Buddhists.

Before Shinran, much of Buddhism in Asia had subscribed to a clear hierarchy that situated priests above laypeople. Shinran broke with this tradition in two distinct ways: He was the first ordained Japanese priest to marry openly, and he was the first to act as a priest and simultaneously live as a family man, wearing robes and ministering to laity but absolutely refusing to live in temples. In looking back at his own life, he declared, “I am neither monk nor layman.” His innovations in lifestyle and religious status opened the way for Shin Buddhism’s radical egalitarianism, which did not consider lay life to be an impediment to religious attainment and allowed women to be fully ordained earlier than many other schools. It was a path that would reveal possibilities for the ongoing development of Buddhism in the West.

Related: Living Buddhism

Like his contemporaries Zen master Dogen (1200–1253) of the Soto-shu [Soto school] and Nichiren (1222–1282) of the Nichiren-shu, Shinran began his career as a monk on Mount Hiei, the headquarters of the dominant Tendai school. All three saw the Tendai ecclesiastical order as riddled by corruption, with too many monks who sought wealth and fame, and hid their wives and girlfriends while excluding women from the sacred precincts of Mount Hiei.

In 1203, Honen (1133–1212), a monk who had recently rejected the Tendai authorities, was teaching a new path of Pure Land practice in which laypeople and the ordained were seen as equals on the spiritual path. This practice could be pursued by anyone, whether as an ordinary member of society, married with a family, or as a celibate renunciant. All that the path required was nembutsu practice, or chanting the name of Amida Buddha, “Namu Amida Butsu.” Through this practice, Honen taught, one would be fully embraced in boundless compassion. Two decades into his monkhood in the Tendai sect, Shinran had difficulty believing that such a path would work. To attain liberation, didn’t one have to renounce this world, let go of attachments, and complete a difficult path of practice? Yet prior to his abandoning the offcial doctrines of the Tendai School, Honen had been one of the most widely respected monks of his day, so Shinran felt there could be some validity to this new approach.

At age 29, Shinran entered into an intensive retreat at Rokkakudo, a temple in Kyoto, in hopes of receiving some kind of illuminating insight or vision. On the dawn of the 95th day of his 100-day retreat, Kannon, the Bodhisattva of Compassion (Avalokiteshvara), appeared to him in a dream and said, “If your karma should lead you to transgress the precept against encountering a woman and joining with her, then I will incarnate myself as the jewel-like woman, adorn your life, and eventually lead you into the Pure Land.” Awakening from this vivid dream oracle, Shinran was convinced of the truth of the way being taught by Honen, became the latter’s disciple, and entered the path of “Namu Amida Butsu.” Like other single-practice paradigms such as Dogen’s zazen and Nichiren’s daimoku (chanting of the title of the Lotus Sutra), Shinran’s nembutsu path focused on a central, approachable practice.

Honen and Shinran, however, had not received official sanction to teach this new path of Pure Land practice. Eventually, Honen, Shinran, and other leaders of the emerging movement were prosecuted as outlaw priests, had their status as ordained monks revoked, were given lay names, and were exiled into the rural countryside. Two of these priests were even executed, having been accused of breaking their vows with ladies of the court. Eventually, when things had died down, Honen, Shinran, and the others were allowed to return, but by this time Honen was elderly and unwell. He passed away within a year.

Shinran meanwhile had come to feel that the farmers, fishermen, and outcasts that he encountered in the countryside were more genuine and down-to-earth: they opened their hearts to the nembutsu path of Amida’s boundless compassion more readily than many of the learned but hypocritical ecclesiasticals who seemed preoccupied with petty bureaucratic rivalries and the privileges of power. He decided not to return to Kyoto. For the next 30 years, Shinran lived and worked among the peasants; he never lived in a temple again. He married a woman named Eshinni, and they became partners both in ministry and in life, raising seven children together. She even had a dream that mirrored Shinran’s own: in her dream, Shinran was an incarnation of Kannon, just as she had fulfilled Shinran’s dream oracle that he would meet the woman who would incarnate Kannon.

Shinran’s thought has continued to inform Buddhism in Japan and beyond, with such concepts as blind passions, foolish being, and boundless compassion becoming part of the English-language vocabulary of Shin Buddhist practice in the West. In Shin Buddhism, the person entrapped in the mental prison of his own making is caught in his own “blind passions” (bonno in Japanese). Passions and desires, like words and concepts, are not negative in and of themselves. It is only when we become obsessed by our ideas about what we think we are or should be that we become blind to the reality before us. Just as love must be allowed to unfold and cannot be forced, our broader experience of life and death can truly unfold only in the freedom of mutual encounter between us and the world, when we are no longer blinded by our desire to force things into a mold that has been preconceived in our minds.

One of the keys to Shinran’s thought lies in the fact that he saw all beings as subject to blind passions, including ordained Buddhist monks and nuns. No one is entirely free of blind passions; no one is devoid of the potential to realize the liberation from their bonds. The encounter with reality, the realization of emptiness, is described in Shin Buddhism as the embrace of boundless compassion (Japanese, mugai no daihi; muen no ji). Although emptiness, being beyond all distinctions, is formless and characterless, the experience of being released from the suffering of our blind passions into the vast, oceanlike emptiness is nonetheless experienced as a positive realization, what Shinran calls the entrance into “the ocean of limitless light” (kokai) of great compassion. Compassion suitably translates the Japanese Buddhist term jihi, as the former comes from the Latin com-, “with,” and passion, “feeling.” Thus, “compassion” is “feeling with” the flow of reality, a compassion that is boundless because it is beyond categorization, ineffable, inconceivable.

Whereas the norm is to see the learned monkhood as well advanced on the path, Shinran saw his lay followers, many of them illiterate peasants, as equal to or even superior to the monks of his day.

The one who is filled with blind passions is called a “foolish being” (Japanese, bonbu), and the embodiment of boundless compassion is Amida Buddha. Blind passion and boundless compassion, foolish being and Amida Buddha: These are terms of awakening in the daily religious life of Shinran’s Shin Buddhist. Furthermore, these polar pairs are captured in the central practice of Shin Buddhism, saying or chanting the name of Amida Buddha in the form of the phrase “Namu Amida Butsu,” meaning “I entrust myself to the awakening of infinite light.”

The nembutsu is derived from the Sanskrit Namo Amitabha Buddha. Namo is the same as the “namas” of the South Asian greeting “namaste,” “I bow to you.” In Pure Land practice, “Namo” or “Namu,” “I bow,” is an expression of deepest humility, naturally following from the awareness of oneself as a foolish being filled with blind passions. Amida Buddha’s name comes from the Sanskrit Amitabha Buddha, which means the “Buddha of Infinite Light” (alternately, Amitayus Buddha, “the Buddha of Eternal Life”). Yet since boundless compassion is always unfolding and never static, the more precise rendering is “the awakening of infinite light.” Just as we often experience a palpable darkness when we are troubled and a feeling of clarity or illumination when we are freed from our worries, the realization of emptiness/oneness comes to us as a vivid sense of limitless light: We become more aware of the presence of nature around us, such as the subtle hues of wild flowers blooming by the roadside.

We can never get rid of blind passions entirely, however, as long as we live in this limited mind and body that we call the “self.” In any moment of release from our ego-prison, we may feel the deep impetus never to complain again, never to prejudge others again. And yet we do complain; we still prejudge. However, once we have been awakened to the working of Amida’s boundless compassion, each moment of ignorance and blind passion becomes another opportunity to gain insight and learn anew, and over time our attachments begin to soften and release a bit more easily. In Shin Buddhism, we greatly value our blind passions as the very source of our own wisdom and compassion.

In the daily rhythm of the life of nembutsu, of saying or chanting “Namu Amida Butsu,” the smallest moments of reflection and appreciation carry as much significance as great realizations. Whether we are actively in the moment of saying “Namu Amida Butsu” or not, our life becomes transformed over time by being steeped in the totality of dharma, through hearing the teachings as well as chanting, bowing, and other bodily practices. Thus, seeing a plant beginning to wilt, I am reminded of my foolishness in forgetting to provide water to the being that gives me beauty, fresh air, and sprouts new life. In hearing my cat meow, I turn to look at my watch, seeing that in my preoccupations I have forgotten his dinner.

Related: Jodo Shinshu: The Teachings of Shinran

Whether we are lay or ordained, women or men, it is only through recognizing our mistakes that we learn and grow. Our blind passions are like fertilizer for the field of our own spiritual development, as blind passions and boundless compassion go hand in hand: the more we become aware of our foolishness, the greater will be the illumination of boundless compassion; the deeper we go into the ocean of boundless compassion, the more we realize how we have been drowning in our own foolishness. It is a process whereby we are illuminated and immersed in the ocean-light of Amida’s great compassion. In chanting the Name of Amida, the true, real, and sincere mind of Amida becomes one with the mind of the follower through the working of boundless compassion. Shinran saw himself as the most foolish being of all and called himself “Gutoku Shinran,” meaning literally “Shinran, the bald-headed fool.” His robes were not so much a sign of religious attainment, but rather a reflection of his self-representation as a foolish being receiving the gift of boundless compassion.

This is a universal message that anyone can relate to. Even the most accomplished Buddhist masters are nevertheless human, have foibles and limitations, and are subject to error and human fallibility. Thus, among the followers of Shinran’s path of Shin Buddhism there were learned monks as well as illiterate peasants, and certainly one might see a master as further along the Buddhist path than a mere layperson. Yet Shinran saw things a bit differently. Whereas the norm is to see the learned monkhood as well advanced on the path, Shinran saw his lay followers, many of them illiterate peasants, as equal to or even superior to the monks of his day. In what is perhaps the most famous passage from the Tannisho, a record of Shinran’s words made by his follower Yuien, Shinran is quoted as saying,

Even a good person attains birth in the Pure Land [realization of the realm of emptiness], how much more so the evil person [who is burdened with the karmic weight of blind passions].

But the people of the world constantly say, “Even the evil person attains birth, how much more so the good person.” Although this appears to be sound at first glance, it goes against the intention of . . . other power. The reason is that since the person of self-power, being conscious of doing good, lacks the thought of entrusting the self completely to other power, he or she is not the focus of [boundless compassion], . . . Amida Buddha. But when self-power is overturned and entrusting to other power occurs, the person attains birth in, [or realizes,] the land of True Fulfillment [the Pure Land of emptiness].

This statement carries a universal significance. It is the human, karmic condition to want to identify with the “good” and to avoid seeing the “bad,” or potential for karmic evil, within. Yet always to seek to present oneself as “good” is to be caught in the workings of the ego self, or what Shinran calls “self-power,” preventing one from opening up to the spontaneous unfolding of buddhanature, great compassion, what Shinran calls “other power” because it is “other than ego.” Shinran’s statement “how much more so the evil person” also carries specific criticism of his contemporaries, learned monks who presume to be the Buddhist “experts” but flaunt their social status and privilege, in contrast to farmers and common folk who lack such pretensions and are in greater harmony with the rhythms of nature, who possess very little material wealth and must live in constant awareness of impermanence. The subtle point here is that Buddhism is a bodily practice first, in which one speaks the nembutsu aloud. Then the heart may open and the mind may follow, but only if one is sufficiently humble and clear of the need to possess and the desire to control the world through the intellect.

Shinran defined two key moments in the arc of the nembutsu path: shinjin, true entrusting, as the moment of realizing boundless compassion, and ojo, birth in the Pure Land, which comes at the end of life. There is a parallel with the story of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni: his attainment of nirvana at age 35 and his entrance into parinirvana, complete repose, at the age of 80. These two moments are also known as “nirvana with a remainder” versus “nirvana without a remainder,” where “remainder” denotes the residue of karma that remains while living this finite life. To realize true entrusting is to be illuminated, embraced, and dissolved into the great light of Amida’s boundless compassion, but it is only at the end of life, entering into the Pure Land beyond conception, that one is fully released from the bonds of existence. Even then, the Shin Buddhist promise is to stop just short of release and return to this world to complete the bodhisattva journey of universal liberation in service to others.

While some may experience a great moment of realization, akin to the Buddha’s realization of nirvana, others may experience a series of smaller moments that are no less significant. Here there is a certain similarity to koan practice in Rinzai Zen, the series of nonlinear problems that the practitioner must pass through. Some experience a great, life-altering breakthrough followed by lesser realizations that aid in one’s maturation; others experience a series of smaller realizations that punctuate a deepening process of awaken- ing. Great or small, little or big, each moment is beyond compare as an expression of the awakening of infinite light.

This is our dance with reality and with ourselves, the rhythm and song of “Namu,” our foolishness, and “Amida Butsu,” the wellspring of boundless compassion that arises from our own deepest, truest reality. Ultimately, even the nembutsu arises not from ourselves, from our own ego, but is experienced as a call from the deepest level of reality, from the depths of our own being, in which the flow of emptiness or oneness is realized in each manifestation of form and appearance. Thus Shinran states, “True entrusting is buddhanature.” The movement of boundless compassion is also known as the Primal Vow of Amida (Japanese, Amida no hongan), the vow to bring all beings to the realization of oneness, spontaneously arising from the depths of existence. The nembutsu expresses our receiving this deep vow to liberate and realize oneness with all beings, because all beings are the self. It is an expression of deepest gratitude, that our lives are sustained within the larger web of interdependence. We are sustained by those who help provide for our livelihood, food, shelter, family, and friendships, and at a deeper level we are naturally moved to express our appreciation for our shared suffering in life and death, our mutual illumination in foolishness and compassion, our oneness in the path that takes us beyond life and death. This is Namu Amida Butsu.

Shinran’s statement “I am neither monk nor layman” comes at the very end of his major work, the Kyogyoshinsho (Treatise on Teaching, Practice, True Entrusting, and Realization). It is a historical statement, describing the circumstances of his teacher and himself in limbo: exiled, defrocked, yet still ministering in the countryside. It is also a philosophical statement in keeping with the twofold truth, with emptiness as the basis of religious attainment that is beyond all categories, lay and ordained. Ultimately, it is Shinran’s own self-expression as a foolish being: “I am not qualified to be regarded as a good monk or a good layman.”

Shinran’s egalitarianism is rooted in the realization of profound oneness with all beings. It is radical in its inclusivity, beyond words and in the depth of self-awareness. Any criticism leveled at his contemporaries in the priesthood, as well as his fondness for peasants and fishermen, came from a place of inclusivity in which Shinran saw himself as the greatest of fools. In a time of great social and political turmoil, he expressed his criticism and advocacy alike from a place of great compassion. Perhaps there is something of value in this for us to consider today.

A Pure Land Buddhist Primer

By Jeff Wilson

Pure Land Buddhism is immensely diverse, in part because it most often exists in combination with other forms of Buddhism, especially Zen and tantra. Among the many traditions that incorporate Pure Land elements are Tibetan phowa practice, which at death directs the mind to Amitabha and transfers one’s consciousness to the Pure Land; Shin Buddhism, which views as the best path the practitioner’s profound gratitude for and entrusting in the Buddha’s great compassion; Obaku Zen, which focuses on the koan “Who is reciting the nembutsu?”; and Yuzu Nembutsu, which directs the practitioner to circulate merit to all beings for mutual awakening.

This diversity has common roots in India, where the primordial buddha Amitabha (Japanese, Amida) and his blissful realm of liberation were foci of devotional awareness from the beginning of Mahayana Buddhism. A central concern for the stream of Buddhism known in the West as Pure Land was inclusion of the masses who had been marginalized by the elite scholastic and meditation schools. This common-person orientation contributed to Pure Land’s success as Buddhism flowed eastward into China, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Pure Land eventually became the mainstream tradition of Buddhism in East Asia, and Pure Land forms are present in all contemporary Buddhist traditions except Theravada. Japanese Pure Land is distinctive in that several independent schools arose, all centered on chanting the name of Amida during everyday life.

The Chinese brought Pure Land practices to North America in the 1850s as part of their syncretic religious traditions, Japanese Pure Land schools began opening temples in Hawaii in the 1880s, and Vietnamese and Korean temples appeared in the 20th century. Today, Pure Land remains a major form in both Asia and parts of the West.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.