Anyone who has ever sat down to meditate knows how easily the mind gets caught up in telling stories and entertaining thoughts. As Tibetan lama Tarthang Tulku puts it, “If we take time to focus on the stream of mental events, we soon observe that we are almost always thinking.” In one way, that seems almost self-evident, but we might still wonder why, since most of our thoughts are routine and, frankly, pretty boring.

The same is true for the stories we tell. Whatever function they may serve in keeping our lives on an even keel, they seldom offer much in the way of new insights, greater clarity, or a sense of wellbeing. They bubble up when we’re feeling agitated or when we’re acting out of habit, and they distract us from paying attention to what is going on in our lives.

That’s why meditation teachers generally suggest not getting involved in the stories that flicker across the screen of consciousness. When we get lost in the content of our stories, we stop being present to our own experience. We “space out,” a term we can take fairly literally, since stories lift us out of our immediate experience and deposit us somewhere else.

Things look different, however, when we start to look closely at the stories we live. And we do indeed live within stories. First and foremost, there’s the story of being a self: the story “Here I am.” It’s not a story we have to put into words, because the self-story is built into our lives at the deepest level. It’s a given, and—as the Buddha tirelessly pointed out—it has powerful consequences for how we live our lives.

Traditionally, the commitment to the existence of the self is considered a wrong view, but there is more to it than that. We don’t just see the self as being real; we inhabit a world in which the existence of the self, situated at the center of what we experience, is a given.

To get a sense of what this means, consider this passage in a book by the naturalist Barry Lopez, describing a journey with Indigenous people of the far north:

If my companions and I, for example, hiking the taiga encountered a grizzly bear feeding on a caribou carcass, I would tend to focus almost entirely on the bear. My companions would focus on the part of the world of which, at that moment, the bear was only a fragment. . . . My approach . . . was mostly to take note of objects in the scene—the bear, the caribou, the tundra vegetation. A series of dots that I would try to make sense of by connecting them all with a single rigid line. My friends, in contrast, had situated themselves within a dynamic event. . . . Their approach was to let it continue to unfold. To notice everything and to let whatever significance was there emerge in its own time.

Lopez is contrasting two different ways of inhabiting the world. His way is to put the self at the center. Events happen and objects appear, but the self, the one who experiences this, is positioned outside what is happening, “taking note” of what happens and “making sense” of it. His companions, in contrast, inhabit a world that is fluid and dynamic. For them, a story is unfolding, and their experience in this moment fits within that story. They are embedded in the world shaped by that story, much as a character in a novel is embedded in the story that the novel unfolds.

A practice that starts from the stories we live makes this ongoing dynamic available. We need not focus solely on this immediate moment (helpful though that can be), because stories are temporal in a different way. The stories we inhabit engage past, present, and future simultaneously. Once we realize that we are always inhabiting stories, we realize that the immediate moment is not where we live our lives. We live across time, in a present that encompasses the past and future—what we might call “story time.” Any experience has its framing story, and every story, provided we let ourselves live it, offers an occasion for deeper appreciation and knowledge.

Understanding the Buddha’s teachings in this way gives them an added dimension we might otherwise miss. Consider the teaching on the five skandhas—form, feeling, perception, conditioning, and consciousness—a teaching specifically introduced to counter the commitment to a self. It’s not just about seeing experience through the lens of the five skandhas, though that’s the place to start. Instead, it’s about living a story—inhabiting a world—that unfolds through the skandhas’ dynamic interaction. When we do, the self-story still operates, but now it’s just another dimension of the understanding we have been conditioned (the fourth skandha) to accept.

Another way to get clear on lived stories is to contrast them to told stories. Consider explanations, stories we tell to make sense of things. Why was I late for work? “Well, the bus broke down, and all the passengers had to transfer to a different bus. So I couldn’t get there on time.”

That’s an example of an explanation as a told story. Look a little deeper, however, and you’ll find a lived story: we inhabit a world where the principle of cause and effect applies, so in the story we live, offering explanations makes sense. If something happens, it’s because something else happened, and we can trace that sequence back. We don’t have to tell ourselves stories about how the principle of cause and effect operates; we just know that it does. Just like the story “here I am,” the story “everything has a cause” is something we take for granted. To be clear, calling the principle of causality a story doesn’t mean it’s false. “Cause and effect” is a true story, at least in the pragmatic sense that it applies to how we go about our day-to-day lives.

Many of the stories we live are equivalent to what we think of as common sense: what everyone knows is true. Of course, we live other stories that are unique to us: stories about who we are and how other people figure into our lives, stories that make sense of what’s happening around us and to us. Again, it’s like being the characters who inhabit a novel. The lived stories make up the background of what’s happening. The told stories advance the plot.

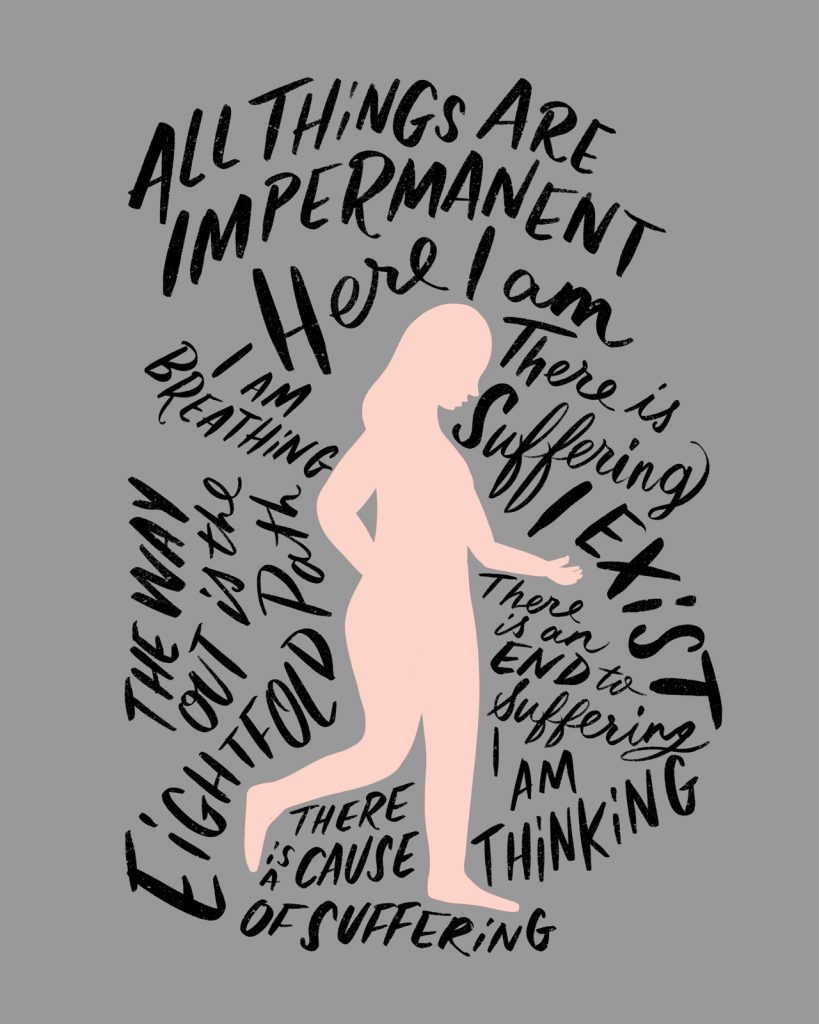

If we accept that we are always living stories, we can see that a lot of Buddhist practice is about changing the stories we live, about getting us to inhabit a new story. I’ve already given one example: the Buddha asks us to question the story that puts the self at the center of experience, offering in its place the story that our lives consist of dynamic interactions among the five skandhas. The teaching on the four noble truths, and especially the reality of suffering in our lives, is another invitation to live a different story. The Buddhist scholar David McMahan speaks of the Buddha’s teachings as “laying out an entire way of being in the world.” That “entire way” is what I call a lived story.

Admittedly, the idea of lived stories can be difficult to get a handle on, largely because they are mostly implicit, abiding in the background of day-to-day life. To use one more analogy, we might think of lived stories as the architecture of our normal thinking. If, for example, you step into someone’s home, you might notice the furniture or what is hung on the walls or the flooring and so forth. But you don’t see the framing and foundation that are the structures upon which everything visible rests. Lived stories are something like that.

The dharma offers many ways to change your lived stories. For instance, you can engage your embodied experience differently, by focusing without judgment on sensations in the body. Or you can imagine the world you inhabit differently, and then let that imagined world come alive. Visualizing the Buddha works this way. It’s an invitation to let the Buddha, with all his extraordinary qualities, be present in the story you are living. The same holds at the level of doctrine: you hear the story that all conditioned things are impermanent, you reflect on it, and you integrate it into your life, which means that the impermanence of all things becomes a part of the story you live, the story that makes sense of the world. At a more fundamental level, living a story is itself an expression of the truth of impermanence. Instead of holding tightly to the fixed identity of self in a world of other fixed identities, you live (like Barry Lopez’s friends) within the flow of shifting events, where past, present, and future alike are in constant flux.

Seeing our lives as stories we live opens up a different way to practice. For instance, suppose I find myself thinking back to the pleasant dinner I had last week with friends at one of my favorite restaurants. There are two parts to that act of remembering. There’s the content of the memory—catching up with my friends on what’s been happening in our lives, discussing plans, enjoying the food and the company. At the same time, there’s the experience of remembering—in other words, the experience of living in that activity of remembering. If the memory arises in passing, I’ll probably focus on the content. If it comes up while I’m meditating, though, I may be more sensitive to the remembering itself, letting the content of the memory slide on by.

Something similar happens when I focus in my meditation on breathing. There is the experience of breathing—air in, air out, belly expanding, belly releasing, and so on. But there is also the lived story “I am breathing,” a story I take for granted. While it doesn’t pull me away from the experience of breathing, it conditions and limits it. My experience of breathing is shaped and confined in subtle ways by the story that the breathing is mine, that it belongs to me.

That’s where learning to be aware of the stories we live can change things in important ways. When we excavate them from the subterranean realm of “what we take for granted,” we make available a different dimension of lived experience. At the same time, because we are focusing on the lived story as a story, we are less likely to be pulled into the story’s content, where we so often get lost.

Consider again the story that my self is the owner of experience. The Buddha taught that the self-story, and the grasping and claims of ownership that come with it, are the source of tremendous suffering and frustration. He offered other stories in its place, as we’ve already seen—not only the story of the five skandhas but also the story that all things and all circumstances are impermanent and constantly changing, including our presumed identity as selves. If we replace the lived story of “me at the center”—the story we have been conditioned from childhood to accept—with the story of impermanence, life looks very different.

Holding the stories we take for granted up to the light of inquiry can be challenging, because we don’t see them as stories at all, but simply as how things are. Here again, the best example is the story of the self as owner. The philosopher Henri Bergson starts one of his books by saying that we are more certain of our own existence than anything else. It’s a basic fact of being human. So how can we question it?

I’d say that the first step is to acknowledge how thoroughly our experience is shaped by the stories we live. And here we’re in luck, because that’s a practice eminently suited to these times. As a culture, we seem to be more committed to our stories, more involved in them, than any other culture in history. True, people have always told stories and always imaginatively lived in them, but today, inventing stories or adopting them has become a way of life: think of social media, conspiracy theories, and identity politics. Our forms of entertainment—movies, television, video games—feed us a steady diet of stories, and still we clamor for more. We curate our online identities on Instagram or TikTok and present them to others as stories ready to be consumed. At a deeper level, we live in a multicultural and tribalized world, one where different stories compete to define the way things are. Even if I insist that my version is the one that’s true, I have to accept that it’s a story, standing on the same footing as your incompatible story. We even are ready to consider the possibility that our waking life could be a simulation, a story crafted by someone else, in which we simply play our assigned roles (as in the Matrix movies).

That’s not all bad. For one thing, we understand very well the danger in being so involved in stories, of living in what the writer Kurt Andersen calls “Fantasyland.” As the historian Daniel Boorstin foresaw more than sixty years ago, “we risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so ‘realistic’ that they can live in them.” For another, our openness to stories, our sophistication about how they work, prepares us to see clearly the constructed nature of the worlds we inhabit. In a sense, stories are our superpower.

If we want to take full advantage of our familiarity with stories, we need to be clear about what stories are and are not. Here, I want to borrow an important way of making sense of the mind from the Buddhist Abhidharma. A systematic presentation of key Buddhist teachings, the Abhidharma identifies six kinds of consciousness: the five sense faculties plus mind as a sixth faculty.

Each of the six has its own range of experience. For instance, when we hear a blackbird sing, hearing-consciousness hears the sound, but it does not identify the bird as the source of the sound. That identification is a story, an explanation, generated by the sixth, mental consciousness. That’s what mental consciousness does: make sense of what the other five forms of consciousness present by organizing them into a story.

Seeing stories as the “output” of the sixth kind of consciousness helps us understand differently the role of lived stories. On the one hand, we see that the lived story informs the whole of experience. I don’t just hear the blackbird; instead, once hearing consciousness has made a sound available, a lived story emerges, along the lines of “Here I am, and what I hear is a blackbird, and here is how I feel about that, and here is what it reminds me of.”

A focus on lived stories helps us recognize that the world I inhabit and experience is much more mental—in that it is more story-driven—than we usually think. I don’t just sense a world and objects in the world; I make sense of it.

At the same time, seeing how the lived story shapes my experience, I recognize that I don’t have to accept its content as the truth of the way things are. The story is only a story. It is one dimension of a field of experience that includes the output of the other five consciousnesses.

All this leads to a way of exploring the mental operations quite different from what we usually think of as meditation. We don’t have to turn away from stories or drop them. We can bring lived stories into our practice. We can be mindful not just of the particulars that show up in our lives from moment to moment, but of the story we are living, the story that informs the whole.

When we get lost in the content of our stories, we stop being present to our own experience.

To practice with stories, we need above all to understand them as stories. If we accept the stories we live as simply the truth of what is so, we are likely to get lost in their content, and thereby lose the opportunity they offer. Marshall McLuhan famously said that “the medium is the message.” That holds for the stories that inform our lives. Whatever the story’s content, what the story communicates is its own nature as story. When we see that, we are ready to engage differently the experiences that constitute our lives.

Here are a couple of suggestions for practices that can lead in that direction. The first, which I’ve mentioned already, arises with respect to the lived story “I am breathing.” There are meditative practices that suggest labeling that act of breathing as “breathing, breathing,” and that is part of it. But that focus does not directly question the story, the “transitional construction” that says, “I am the one who is breathing; it is my breath.” That’s where we want to look.

You can use the basic meditative practice of focusing on breathing to call the self-story into question. Just let breathing breathe. When we say, “It’s raining,” there is no need to look around for the “it” that is doing the raining. In the same way, there is no need to maintain the existence of the self that is doing the breathing. When you switch in your practice from the story “I am breathing” to the story “it’s breathing,” you can be more directly aware of the self-story arising.

You can take this practice a step further. When you “pay attention” to breathing in meditation, you actually tend to reinforce the role of the self, because the self-story tells you that it’s the self who is paying attention. Again, it doesn’t have to be that way. Awareness of breathing simply goes along with the breathing. Just as there is no one breathing, there does not have to be anyone watching or paying attention.

Another way of decentering the self has to do with the temporal dynamic of stories, which I spoke of above. The self operates in linear time, a time that unfolds in a sequence of moments from past to present and future. If you relax into the flow of experience, however, you will find that between any two linear moments, there is another moment that does not fit into the same linear sequence. For instance, between two moments of breathing, there might be a moment occupied by a stray thought, or an itch. Any one of those “between moments” could trigger a whole new and completely different linear sequence, with its own content. In fact, that’s what happens when we get distracted.

Here’s the alternative. Instead of getting pulled into a new sequence of linear time, keep looking for those “between moments.” Soon enough, you arrive at moments that are unnamed and thus not part of any potential linear sequence. The more you develop sensitivity to those unnamed moments, the more you free yourself from the content of the stories you inhabit—and the more you can appreciate stories themselves in their arising. And that means appreciating more fully your own life.

Many kinds of meditation involve focusing with increasing intensity on one specific object: the breath, a visualization, sound, or just about anything else. Learning to engage the stories we inhabit—the stories we live—is a very different kind of practice. Stories are complex, multidimensional. They invite us to engage our lives as a whole, and they make the whole of our lives—including the stories we tell—available to value and to explore.

One final point. The more familiar we grow with stories in operation, the more we turn away from their specified content to inhabit the field of experience to which they give form. As this happens, the hold they have on us loosens. That matters for our ability to be fully present in our lives, but it matters also for stories that take form as ideology, or as implicit bias, or in conspiracy theories or stories of tribal identity. Not tied to what such stories have to tell us, not insisting on the truth of their content, we draw closer to being free.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.