My first job after college was an editorial assistant position at a daily paper. “Editorial clerk” was the official title, but everyone in the newsroom still used the old term “copy kid” (or simply shouted “COPY!”). It was one of the many bits of jargon treasured by the editors. Of all the terms, from the ledes down to the kickers, the one that seemed strangest to me was a relatively ordinary word: story. Before working in news, I talked about reading articles. “Story” sounds less serious, less concerned about the truth. After all, a story can be a work of fiction.

I think those editors were revealing a—perhaps unconscious—belief: that even our supposedly objective accounts of the world are stories that we make up. We leave out details, whether or not we realize it, to keep people listening and to make a point, be it about ourselves (I’m smart/cool/interesting) or society (People are kind/rude/weird).

“Drop the story” is a common instruction for Buddhist practitioners these days, the idea being that if we can recognize our stories as stories—as always, to some degree, fictionalized—we may realize that we don’t have to take them so seriously. But that doesn’t mean we can or should drop all our stories all the time. If the 13th-century Zen master Dogen was right when he wrote that to study the self is to forget the self, then perhaps we might also say that to study the story is to drop the story.

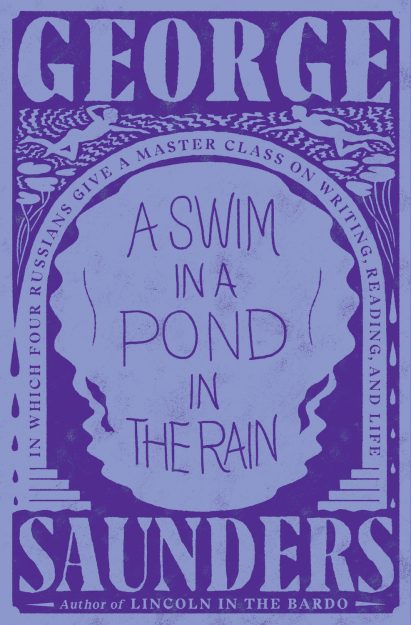

By George Saunders

Random House, Jan. 2021, $28, 432 pp., cloth

In his latest book, A Swim in the Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life, George Saunders—the acclaimed author of such works as Lincoln in the Bardo and The Tenth of December—suggests that reading stories can be a way of studying the self. Adapted from a course he teaches at Syracuse University, the book consists of six short stories by Chekov, Tolstoy, Gogol, and Turgenev, and six essays by Saunders analyzing the stories. In addition to being a wonderful resource for aspiring writers, especially those who aren’t fortunate enough to be one of the six candidates selected for Syracuse’s graduate fiction-writing program each year, the book also teaches Saunders’s approach to reading as a space for reflection and mind training. As he writes in the introduction:

To study the way we read is to study the way the mind works: the way it evaluates a statement for truth, the way it behaves in relation to another mind (i.e., the writer’s) across space and time. What we’re going to be doing here, essentially, is watching ourselves read (trying to reconstruct how we felt as we were, just now, reading). Why would we want to do this? Well, the part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world; it can deceive us, but it can also be trained to accuracy; it can fall into disuse and make us more susceptible to lazy, violent, materialistic forces, but it can also be urged back to life, transforming us into more active, curious, alert readers of reality.

If you, like me, hear Buddhist overtones in this paragraph, you will be interested to find an explicit reference to Buddhism in the very next paragraph, albeit to illustrate a different point. Saunders is a longtime practitioner in the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism, which makes this reading seem more likely, but we don’t have to guess at his intention. In a Tricycle interview in February, Saunders remarked:

I think I was performing a species of meditation long before I knew what that was, while I was writing. Just that experience of concentrating on a piece of prose. . . . In that state, I can now observe, rumination goes quiet(er). So, when I finally started trying to meditate, I felt at home there. The states aren’t identical but are, I think, related.

Is A Swim a practice guide to reading and writing fiction as a form of Buddhist meditation? No, not exactly. But if one were looking for a book on that subject, they might not find a better one.

While Saunders is not an empowered Buddhist teacher, he is a Buddhist and a teacher, and his wish for his students is not merely that they become successful in their careers but that they find what makes them “uniquely themselves.” In other words, the task at hand is to know thyself. This advice gets a more nuanced treatment, however, when Saunders explains that each of us has many selves.

Anyone who has created an artwork that they are halfway proud of is familiar with the sensation that the art is somehow greater than the artist. Some creatives say that God works through them or give credit to unseen muses. Saunders sees it this way: a writer works on a story over time, going through many revisions (and often getting feedback that leads to more revisions). Each time a writer returns to the story, it is as a different version of themselves. By the time a story gets published, it has been worked on by so many versions of “you” that the one you are at any given moment cannot imagine writing it or, later, having written it.

There is an important lesson here for writers, especially new ones: The first draft is going to be bad. At any given moment, even the best writer is a bad writer, at least compared with the countless later versions of that same writer laboring for hours on various drafts. This realization can be freeing. Go ahead and write something bad. Make it better later.

This advice is not always easy to follow. It requires admitting that your greatest accomplishments are not entirely “yours.” It means seeing that you are not always you, and that you will not be able to go on being you forever. That’s because, of all the stories we tell, the story we most often mistake for nonfiction is the one about who we are. It’s similar to the Buddhist concept of no-self. Only in Saunders’s version it may be called “no-self in particular.” He writes:

The instant we wake the story begins: “Here I am. In my bed. Hard worker, good dad, decent husband, a guy who always tries his best. Jeez, my back hurts. Probably from the stupid gym.”

And just like that, with our thoughts, the world gets made.

Or, anyway, a world gets made….

All of this limited thinking has an unfortunate by-product: ego. Who is trying to survive? “I” am. The mind takes a vast unitary wholeness (the universe), selects one tiny segment of it (me), and starts narrating from that point of view. Just like that, that entity (George!) becomes real, and he is (surprise, surprise) located at the exact center of the universe. . . .

So, in every instant, a delusional gulf gets created between things as we think they are and things as they actually are. Off we go, mistaking the world we’ve made with our thoughts for the real world.

We are stuck inside our stories about ourselves and our world. Buddhists from various traditions have developed practices to get better at breaking through this delusion. In A Swim, Saunders offers a different approach: become better storytellers.

How do we do that? The short answer: by practicing, of course, but also by examining our minds when we read a story. As any Buddhist practitioner knows, “watching the mind” is easier said than done. So Saunders leads by example, allowing us to observe his thought process as he focuses on what captures and holds our attention from line to line, what immerses us or takes us out, what leaves us feeling satisfied or disappointed.

Of all the stories we tell, the story we most often mistake for nonfiction is the one about who we are.

Reading A Swim (or, to be honest, mostly listening to the delightfully narrated audiobook while I lay on my back during a particularly bad string of migraines), I was reminded of my time as a copy kid, when the main perk of the minimum-wage position was ample downtime to read Gogol and Dostoevsky. My goal at that time was to be a fiction writer, but I figured that if I could in any way earn a living doing something related to writing, that would be better than the alternative. At the time, I was struck by the juxtaposition of the often frivolous “true” stories covered by the media and the deeply meaningful works of fiction.

When we know that a story is made up, the author has to work a lot harder to get it to feel true, by sharing an essential truth about themselves (as many selves as it takes) that resonates with the reader. But there’s no way to know for sure if it will, because each reader will come to a story in their own way.

That includes how the person we are now views the stories told by the person we used to be. What do I think about the young man sitting in the newsroom? Was he an ambitious writer pursuing a nobler art? Or was he an arrogant kid thinking he knew more about real writing than the professional journalists in the room who had been writing longer than he had been alive? I don’t know how much truth there is to either of these stories, but without them, I’d have nothing against which to consider fact or fiction. It’s only in the telling and retelling and editing and re-editing of the story that I can find any ground at all.

I think this is what Saunders was getting at in his book. But my sense that we might have been seeing eye to eye is another story, as he reminds us in his closing remarks:

If something in this book lit you up, that wasn’t me “teaching you something,” that was you remembering or recognizing something that I was, let’s say, “validating.” … You didn’t need me to be here, to know what you thought of these stories.

♦

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.