I STUDIED with Allen Ginsberg in 1976 at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. It was a six-week summer course in Boulder, Colorado. I was twenty-eight years old and the path of my life was set, even though I didn’t fully know it. About fifteen years later I had the privilege of teaching with him in L.A. And the following year I taught a weekend course and forum with him again for Pacifica College in the same auditorium in L.A. There were six hundred students.

We each taught half the room and then switched. I gave a talk about practice. He read his poems. On the last morning we had breakfast together in the hotel. He ordered only low-cholesterol food. He said it was his doctor’s orders.

I called my friend Barbara Schmitz, whom I had met in his class so many years before. “Imagine,” I said, “I’m teaching with Allen Ginsberg.”

“Don’t you remember what you said back then? ‘He doesn’t recognize me now, but some day he will.”’

“I said that?”

“Uh-huh.”

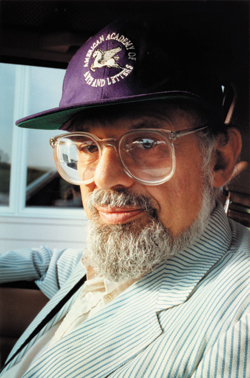

He has been dead for nine years and I miss him. Whenever I lead a retreat I pin on the altar a yellow-framed photo of him sitting cross-legged in meditation position. He is wearing a sly little smile on his face. Right in the middle of effort, don’t be serious, he seems to be saying—or who are we anyway? he asks. Many of my students don’t seem to know what to make of Allen Ginsberg. Some think that he looks like an old man. And some recall rumors of his sexual escapades.

He used to sing, accompanied by his harmonium, a song he’d written called “Gospel Noble Truths”: “Sit when you sit; talk when you talk; cry when you cry; lie down when you lie down and die when you die.” He’d repeat the phrase “die when you die” several times at the end in a wavery voice. He wasn’t a good singer, but the students liked hearing him. His voice was so sincere. It gave you courage and made you want to step up and sing too.

The leaves were so green that summer in Boulder when I first studied with him. When I was alone I’d sing his song at the top of my lungs in my own crooked voice. He was one of my most important teachers.

All over again I want to honor him. After a long walk up the side of a mountain, I want to reach back one more time into the same dark past I wrote about before to say, Thank you again, you are in the lineage of my fifty-eight years.

It is our hope that writing releases us. Instead maybe it deepens the echo. We call out to our past and the call comes back. We are alone—and not alone.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.