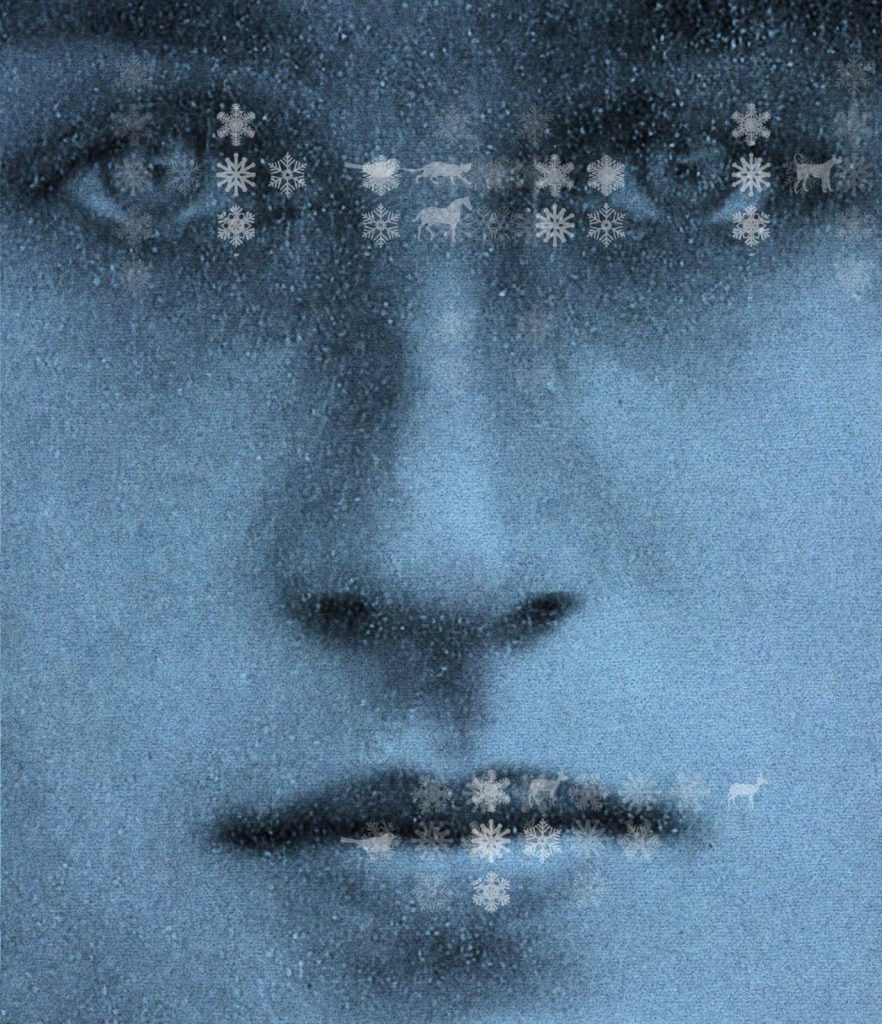

Outside my window

it keeps reciting itself—

the snowflake sutra.

–Jan Häll

Although written texts are venerated by all major spiritual traditions, literacy itself may be at the bottom of our current ecological crisis. Beginning roughly 5,500 years ago, the movement from oral to written culture led human beings to adopt increasingly abstract, disembodied ways of thinking that reinforced their feelings of separation from nature.

The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss saw the problem clearly in 1974. In Myth and Meaning, he observed that the difference between societies with writing and those without written language was that the former wrote almost entirely about themselves, while the latter, so-called “primitive” people, had a vast oral lore about plants and animals, landscape and weather, and all other aspects of the natural world.

Preliterate cultures were not anthropocentric. In fact, the earliest cave art—from Lascaux to Chauvet—is almost entirely devoid of human forms. The first “sutras” were not texts at all, but the closely observed, lovingly rendered shapes of mammoths and woolly rhinos, lions, bison, and bears.

The best-of-season haiku for Winter 2023 invites us to reenter a world in which wisdom, though bypassing the inherently anthropocentric filter of written language, is once more rooted in our direct, sensual experience of the world around us. At home in his native Stockholm, the poet watches snowflakes falling ceaselessly outside his window. The very silence of that falling seems to demand that he enter more deeply into communion with them, listening with the eye rather than the ear.

In some schools of Buddhism, a sutra is seen as more than a sacred text. For instance, the Lotus Sutra is regarded by Nichiren Buddhists as “the Entity of the Mystic Law.” Those who chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, the title of that sutra, unite with a universal life force that animates all things from within. Even the weather.

The poet could have described his snowflakes in terms of writing, given that he compares them to a sutra. But he makes a special point of not doing that. The snowflakes are reciting the sutra. More than that, they are the sutra.

It is a remarkably simple poem. As the snowflakes fall, covering the city on a winter day, the poet imagines them ceaselessly reciting the sutra of themselves. Or maybe he doesn’t imagine that. Maybe he witnesses it—and, in so doing, unites with the Snowflakes of the Mystic Law.

It is worth noting the poet’s artistry in the second line of the haiku: “it keeps reciting itself.” The season word suggests a feeling of delicate, soundless beauty. And yet, taken as a whole, the poem conveys a feeling of tremendous cumulative power. The “snowflake sutra” is a storm.

♦

The Tricycle Haiku Challenge asks readers to submit original works inspired by a season word. Moderator Clark Strand selects the top poems to be published in Tricycle with his commentary. To see past winners and submit your haiku, visit tricycle.org/haiku. To read additional poems of merit from recent months, visit our Tricycle Haiku Challenge group on Facebook.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.