Tibet: Through the Red Box

Peter Sis

Farrar Strauss Giroux: New York, 1998

58 pp., $25.00 (cloth)

In Tibet: Through the Red Box, Peter Sis has created a picture book for children that can speak eloquently to their parents as well. Based on bedtime stories Sis was told as a child, the book was written as a tribute to his father, whose Tibetan travel diary from the 1950s is the Red Box of the title.

In Tibet: Through the Red Box, Peter Sis has created a picture book for children that can speak eloquently to their parents as well. Based on bedtime stories Sis was told as a child, the book was written as a tribute to his father, whose Tibetan travel diary from the 1950s is the Red Box of the title.

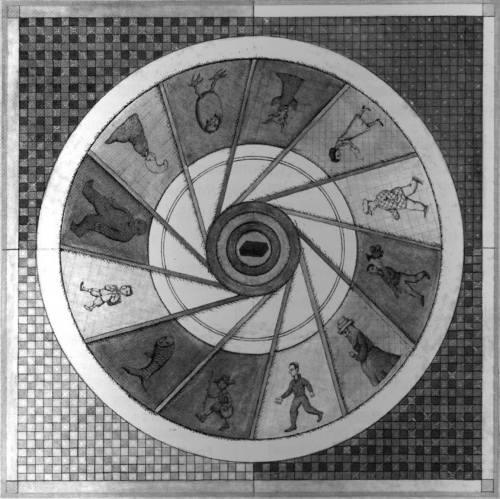

Sis uses these exotic tales to explore what happens when a parent’s memories become the images that introduce a child to the wider world. And it’s his achievement as an illustrator to have found a Tibetan inspiration for putting this complex process into visual terms. His scrapbooklike compositions, in which different voices and points of view come together to form the bigger picture, resemble mandalas in Western translation.

Author of previously published children’s books about Columbus and Galileo, Sis has written Tibet: Through the Red Box in the form of two parallel journeys of discovery. The first is his father’s journey as a filmmaker sent by the Communist government of Czechoslovakia to record the construction of the China-Tibet highway. The second is the son’s own journey through memory as he returns to Prague from the United States, to which he had defected in 1982, and peruses the contents of the Red Box.

The heart of the book is the account of the father, whose position as an observer of the Chinese drive west records his own changing attitude towards socialist brotherhood. (It’s not so hard to see how Tibet and China might stand in for Czechoslovakia and Russia in this context.) Sis senior gets separated from the bulk of his party and wanders in Tibet, eventually reaching Lhasa itself. In classic discovery-story style, his progress becomes a path to personal knowledge, but his association with a politically implicated enterprise gives his account a self-awareness that other Tibet-drawn Westerners often lack.

This remarkable account from the fifties is bracketed—and the question of its “truth” thus complicated—by the second layer of story: Peter Sis’s discovery of the red box. It’s in mining his father’s rich bequest of recollection, scholarship, and fairy tale that Sis’s graphic technique really comes into its own. Within the intricate, Tibetan-inspired designs of the book, Sis has combined diary entries, notes, maps, and official stamps to recall Kipling’s description of a mandala—“half written and half drawn.”

Served such a feast of clues, each reader becomes a private detective: Which voice do I trust? What really happened? What part is fact, what is fiction? Sis is not only relating tales that were embellished for him by his father; he is also recasting them for a whole new audience.

Tibet: Through the Red Box is far from an escapist entertainment, or fantasized tales just for children. Sis maintains a sophisticated take on what’s at stake in the representation of history or geography through narrative. By situating his Tibet among such artifacts and traces of story, the author—himself an exile from his homeland—underscores the loss of country.

The book’s two journeys merge at the end. In a haunting sequence, the elder Sis’s entry to the Potala is made to represent Peter Sis’s quest for reconciliation with his father. The final encounter in the throne room depicts a boy Dalai Lama—much younger than he would have actually been at the time— who can be seen to stand in for the author’s own childhood self.

The dedication on the flyleaf reads: “From son to father and father to son.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.