Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and Race for Empire in Central Asia

Karl E. Meyer & Shareen Blair Brysac

Counterpoint, 1999

646 pp., $35 (cloth)

The Tournament of Shadows was the Russian name for the contest the British called the Great Game: the clandestine struggle among colonial empires for control of the central Asian heartland. It was played on a field that stretched from the Indian Himalayas to the trackless wastes of the Takla Makhan Desert and from the marches of Tibet to the shores of the Caspian Sea. Commencing in the early nineteenth century, its effects are still apparent today, in war-torn Afghanistan, in the newly independent Muslim states of central Asia, and in Chinese-occupied Tibet.

What is remembered as a romantic duel among larger-than-life frontiers-men was essentially a battle among rival imperialists, engaged in an often cynical struggle for power over central Asia. Yet the players acknowledged each other’s right to imperial expansion, and they shared a sense of adventure and of being pan of a Christian “civilizing mission.” They were mostly frontier officers, whose bold actions could bring vast swaths of Asia under their nation’s flag (and win fame and glory for themselves). Men of action, they were the very opposite of the gray-suited bureaucrats who ruled, then and now, in the capitals of empire. Much of their continuing appeal surely lies in that contrast.

Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac are not the first to have chronicled this colorful saga or to have described the exploits of its heroes. But their account is surely the most readable, and they have succeeded admirably in their aim of producing a work that will inform and entertain the general reader while bringing new sources and insights to the specialist.

In their enthusiastic pursuit of their characters, the authors sometimes stretch the definition of the Tournament of Shadows beond its generally accepted boundaries—into such topics as the Indian “Mutiny” and the correspondence between the Russian mystic Nicholas Roerich and the American Vice President Henry Wallace. But these diversions are always entertaining, and the wide perspective means that events and characters are seen in their historical and cultural contexts. Explanations of important ideologies such as the rival British imperial schools of thought—the “forward school” and the “school of masterly inactivity”—are succinctly outlined. Nor is it forgotten that the greatest lasting benefit from the tournament was in the field of knowledge

The work centers on the fascinating cast of characters who played the Tournament of Shadows. They include the Russian explorers Przhevalsky and Kozlov, Sweden’s Nietzschean superman Sven Hedin, heroes of the British empire such as William Moorcroft and “Bokhara Burnes,” along with Americans such as the diplomat and adventurer William Rockhill, who dreamed of reaching Lhasa, and Dr. W. M. McGovern, who did reach the Tibetan capital in 1923. Of the great travelers to central Asia only the chronically modest Ney Elias is missing, while forgotten figures such as the Ohio war correspondent Januarius Macgahan, who reported on Russia’s Khiva campaign and became a hero of Bulgarian independence, and Duleep Singh, who might have ruled the Punjab with the support of the British or the Russians, are restored to prominence. And the authors do not neglect the perspective of local rulers such as Afghanistan’s Dost Mohammed, who was left to wonder why the great British Empire bothered to take “my poor and barren country.”

The personality-centered approach works particularly well in explaining the role of the European powers in Tibet. After the British Younghusband mission had reached Lhasa in 1904 and found no trace of the “Russian threat” that caused the mission, British Tibetan policy veered between the approaches of the “Roundhead” Charles Bell, friend of the Dalai Lama, and the “Cavalier” F M. Bailey, who thought the Tibetans should do as they were told by the British! The half-forgotten Nazi mission to Lhasa in 1938-39 is discussed, as is the visit of the Americans Ilya Tolstoy (grandson of Leo) and Brooke Dolan during the Second World War. This visit paved the way for closer American ties with Tibet, and by the 1950s, it was the CIA that had taken over the role of Britain’ s frontiersmen, parachuting Tibetans back into their homeland to fight the Chinese.

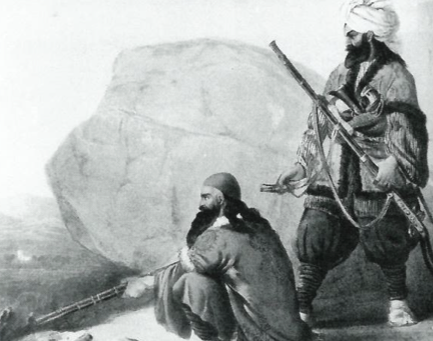

This is a lively, page-turning history, aimed particularly at the American reader. It has a good selection of illustrations, clear maps, and well-chosen quotations. There are a few minor errors, mostly due to problems within the original sources, but it is a work that will be enjoyed by all readers with an interest in Asia.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.