The 9th-century poet Po Chü-i (pinyin, Bai Juyi) once visited an eccentric Chan master known as Bird’s Nest. Finding the monk meditating in a tree, the poet cried, “Hey, master! It looks dangerous up there!”

“Not so dangerous as where you stand!” replied Bird’s Nest.

Po Chü-i, who served as governor for several small provinces, considered the precariousness of his political position and concluded, a bit ruefully perhaps, that the master was probably right.

“Then please explain for me the teaching common to all of the buddhas,” he implored.

In answer, the master quoted a familiar passage from the Dhammapada:

Avoid evil,

Practice good,

And purify your mind—

Such is the teaching of all buddhas.

Disappointed to have traveled so far only to receive a teaching he knew by heart already, the poet complained, “But any three-year-old knows that much.”

“A three-year-old knows it,” said Bird’s Nest, “but a man of eighty cannot do it.”

The story is well known in Zen circles, where it is often cited as part of the ceremony for taking the precepts. It reminds us that in Buddhism there are no exemptions from the obligation to lead a moral life. The story doesn’t tell us how to lead such a life—only that it is difficult, but nevertheless required.

Step Four of the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous reads: “Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.” Those who recover in A.A., or one of the many other Twelve-Step programs it has inspired, undertake a process of rigorous moral accounting whereby they review all of their relationships from childhood to the present day in order to determine where they have fallen short in their behavior. Later, they will confess these shortcomings to their Higher Power, to themselves, and to another human being, and begin the lengthy but ultimately liberating process of setting things right again.

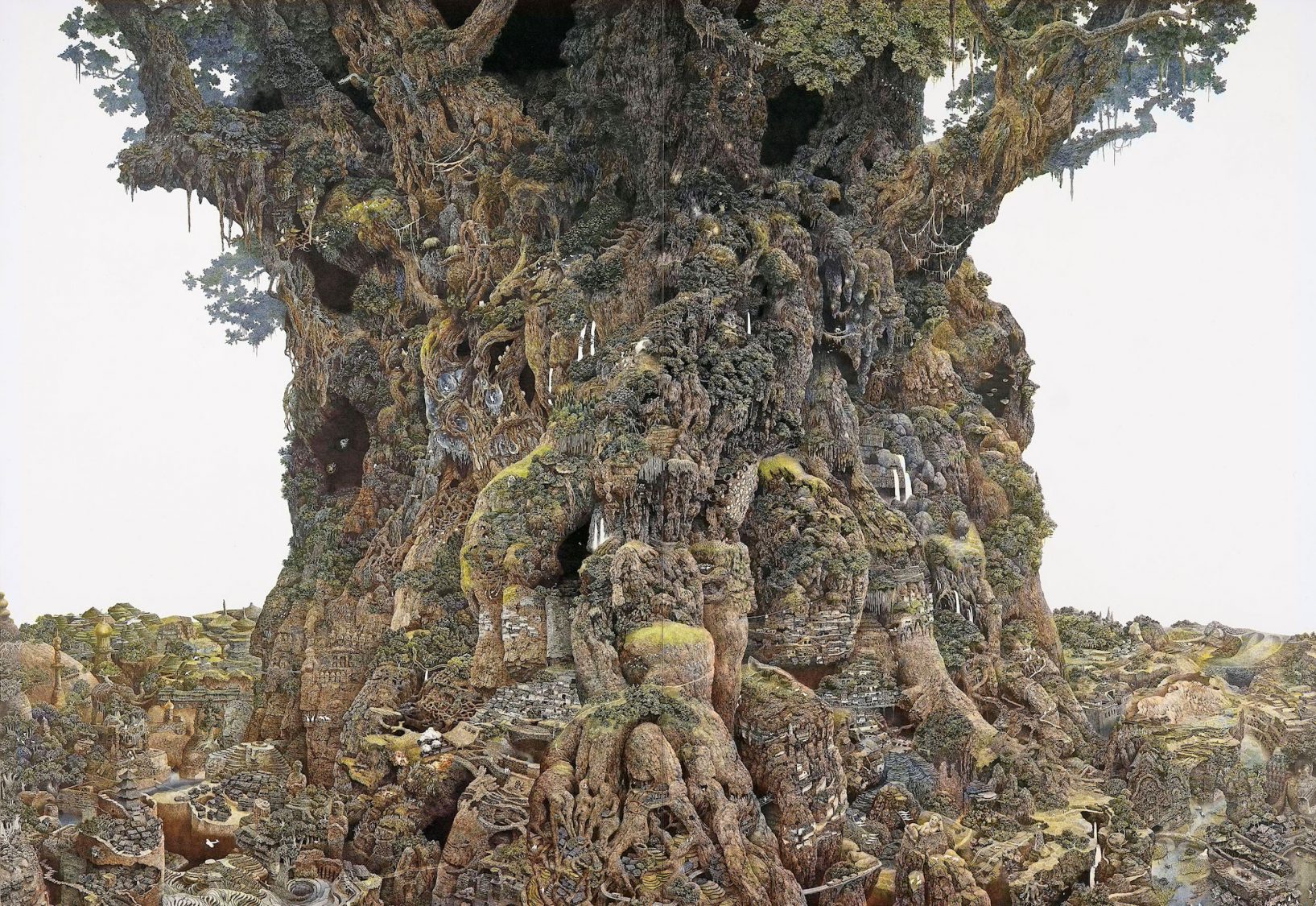

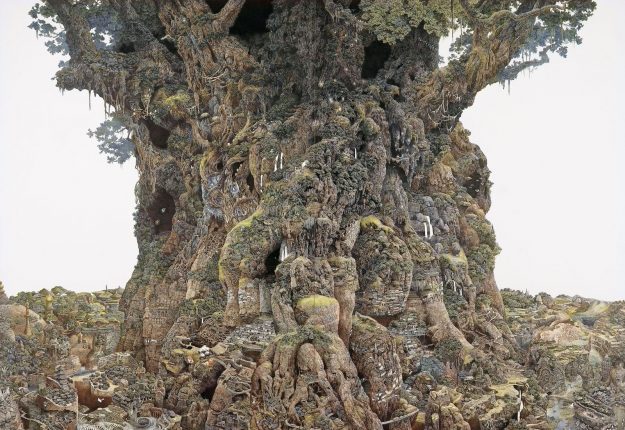

Those seeking to recover from a culture addicted to material excess must do the same. Only, when it comes to Step Eight—“Made a list of all those persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all”—we extend the rights of personhood to other species, and even to those insentient processes that support the life of the planet. Animals are people, too. As are plants. And water. And soil. This is the fundamental insight at the heart of all eco-spiritual work. But to get that insight, we have to get with the big picture. To get that insight, we have to climb a tree.

In the spirit of a discipline one might call “spiritual archaeology,” I would like to suggest that it is not possible for a human being to perch on a high limb for any length of time (much less actually meditate on one) without remembering what it felt like for our first ancestors to live there—not just in the forest, but of it, connected in the most intimate way possible to those primordial sources of nutrition and protection which today, when it is possible to consider them from a somewhat great cognitive distance as commodities, we would call trees.

When it comes to reconnecting with our Original Mind, we could do worse than climb a tree. When it comes to getting a bird’s-eye view on our culture—how it works, where we stand in it, and where it is headed—we couldn’t possibly do better. The ground is too low a vantage point. A satellite is too high. A treetop shows us the world we live in and, provided we are willing to look very carefully, how we live in it. The view from a treetop shows us how the planet keeps us alive.

I’m guessing that is what happened to Julia Butterfly Hill on her two-year odyssey atop the 1,500-year-old California redwood tree she christened “Luna”—an act of civil disobedience against the Pacific Lumber Company loggers who were clear-cutting the forest. Hill later wrote:

When I felt called to help the redwoods…I had no idea what was coming, I was just following a deep, guiding intuition. The reality is that in much of industrialized societies, we are completely addicted to comfort. We are a society of addicts. When confronted with this addiction, we react just like addicts with denial, accusations of others, and often times clinging even more to our addictive behaviors.

Since reading Hill’s story and hearing some of the insights gained from her sojourn in the tree, I’ve been looking for the Bird’s Nest story. I know it’s there. Somewhere, in one of the interviews she gave by satellite-phone, someone is bound to have said, “Hey, Butterfly! It looks dangerous up there.” In response to which I’m pretty sure I know what she said.

For readers who wish to access all Twelve Steps of Ecological Recovery, the remaining eight steps will be made available as an interactive web feature on tricycle.com in September. Future Green Bodhisattva columns in the magazine will cover topics of current ecological and environmental interest.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.