At the waning of the hunger moon in early February, frozen ground thaws. The ancient pagan calendar marks this season as a time of rebirth and growth of imagination. New fire lit on the cold ash of winter’s bone illuminates the primal trinity of poetry, smithcraft, and rising fertility at the pale rim of the year.

In the formal cycle of the Buddhist calendar February is the grave season of the historical Buddha’s death and final entry into parinirvana. Last year during this time I journeyed to northeastern India with a group of Zen pilgrims, traveling in the footsteps of the Buddha. At the close of our pilgrimage we visited the “mud and daub forgotten forsaken place” of Kushinagar, where the Buddha lay down to die between two stately Sal trees almost 2,600 years ago. In that lonely grove the Buddha admonished his grieving disciples, “I declare to you, all conditioned existence is of a nature to decay. Strive untiringly!”

In Kushinagar we visited the solemn Mahaparinirvana Temple mentioned in the travel diaries of the 7th-century Chinese pilgrim Hsuan-tsang. Enshrined in Kushinagar is a massive 18-foot-long carved stone figure of the Buddha reclining in final nirvana, his rock features gleaming with a bright epidermis of gold leaf. A crowd of Buddhist pilgrims was gathered in the temple, the smell of damp feet and burning incense filling the air. Tibetan monks chanted dolorous basso profundo prayers. Circumambulating Cambodian and Sri Lankan monastics draped lengths of saffron and amber silk over the reclining Buddha. A devout sangha of Thai lay women dressed in pure white bowed in full prostration, offering pink lotus flowers to the parinirvana figure while our Zen group sat in cross-legged silence in the shadows of the temple.

I confess that it was a gift to grieve and be grounded in Kushinagar’s gritty crush of Buddhist humanity. Although the Mahaparinirvana Sutra proclaims the Buddha’s final entry into nirvana as marked by four grand attributes—eternity, bliss, true self, and purity—I prefer to stay grounded in the mineral hiss of elemental gravity strengthened by the graphic sorrow of a reclining stone Buddha.

The Unitarian minister Victoria Stafford reminds us that “with our lives we make our answers. . . to this ravenous, beautiful, mutilated, gorgeous world.” We live in challenging times. Global climate change accelerates, fueled by human greed and denial. Conditioned existence is being dismantled with violent force by flood, fire, fracking, and famine as well as war, poverty, and unprecedented loss of biological diversity. What is the creative response of engaged meditation infused with a commitment to environmental leadership in these times?

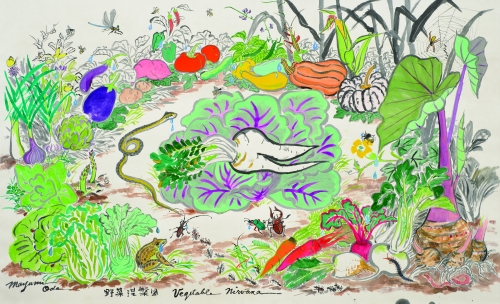

Since returning home from India, I keep a single sal leaf from Kushinagar on our home altar. Also on the altar is a beautiful print, Vegetable Nirvana, painted in the traditional Japanese style of ink and natural color by my close friend and dharma sister, the artist and activist Mayumi Oda. Having been in her homeland, Japan, during the March 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear power plant, Mayumi Oda offers her art as a prayer for new birth in dangerous times.

In Vegetable Nirvana, Oda’s parody of a well-known 18th-century painting, the Buddha takes earthen form as a giant white daikon radish, Raphanus sativus var. longipinnatus, grown since 500 BCE from the Mediterranean basin to China. In the painting, this noble root reclines on a bed of red cabbage leaves, surrounded by a living matrix of colorful vegetables dressed in bright practice robes of purple eggplant, vermillion tomatoes, and lime green taro. Among this pageant of practitioners, lively insects buzz while an attentive frog and weeping serpent pay homage to the World-Honored radish at the root of the world.

In this season of creative upswelling and fertility, Vegetable Nirvana is a strong reminder of the oldest meaning of nirvana: to blow out or extinguish all concepts. Here the Buddha manifests as root substance, radical food for a ravenous world. As the haiku poet Kobayashi Issa (1763–1827) fully understood:

The man pulling radishes

pointed my way

with a radish.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.