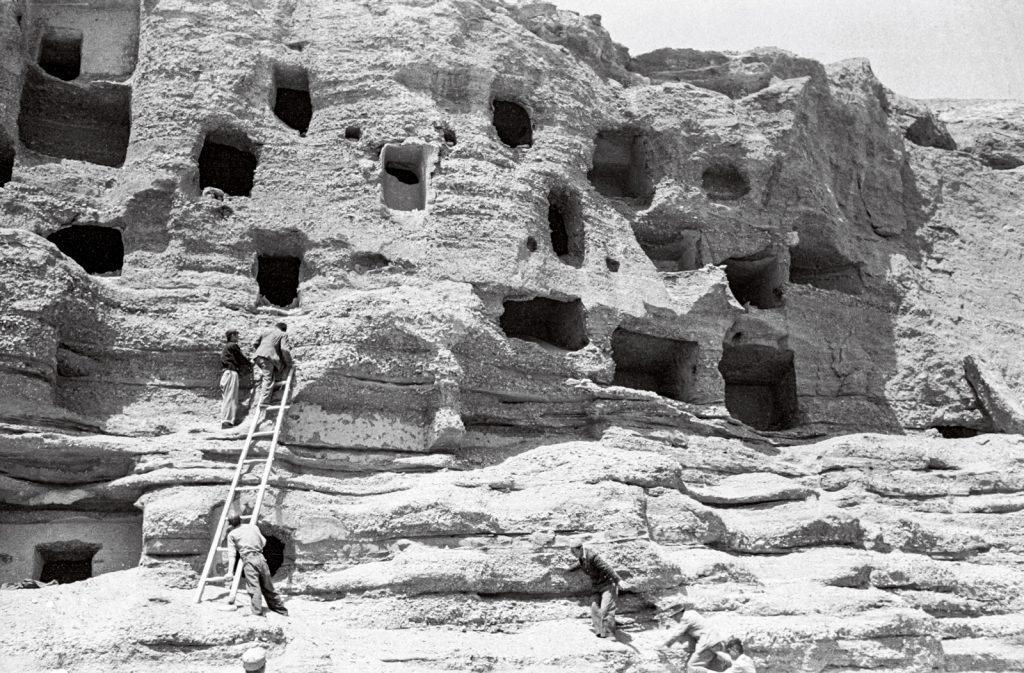

In the spring of 1943, newlyweds James and Lucy Lo took leave from the Chinese news agency where they had first met to embark on a photography expedition. Their sights were set on an ancient network of Buddhist caves carved into cliffs at the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in northwest China. Soon after, they arrived by donkey-drawn carts at the oasis city of Dunhuang, an important trading hub along the Silk Road from the 4th to the 14th century. They didn’t have much of a plan or any expertise in Buddhism, but they would spend the next 18 months at this historic crossroads, exploring hundreds of grottoes and documenting the over 45,000 square feet of vibrant murals and 2,000 sculptures and artifacts housed within them. And what began as a passion project quickly turned into one of the most ambitious surveys of Dunhuang’s Yulin and Mogao Caves, the latter now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

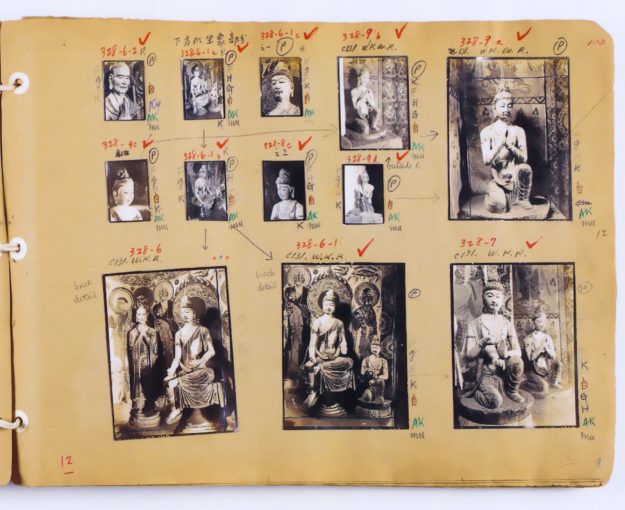

The Los ended up extracting a cache of manuscripts that today make up the largest collection of Dunhuang texts in the United States. The more than 3,000 photographs they amassed have proven invaluable to researchers, archaeologists, and art historians because they preserve perspectives of sites or features that are now long gone, badly damaged, or inaccessible. In a new book featuring several hundred black-and-white photos from the Lo Archive, many of those scholars are paying it forward by bringing even more viewpoints on the caves to light. The retrospective Visualizing Dunhuang: Seeing, Studying, and Conserving the Caves, published in June, is the final work in a nine-volume set of the Lo Archive photographs put together by the archive’s custodian, the Tang Center for East Asian Art at Princeton University. It is a monumental contribution that furthers our understanding of significant developments taking place in early Buddhist doctrine, art, and architecture, as seen through the Los’s lenses.

The ten contributors to Visualizing Dunhuang, all specialists in Chinese art and architectural history, discuss a wide range of topics, from expeditionary photography to history, archaeology, and conservation challenges. Filling 400 pages are essays on patronage, military and dynastic connections, and evolving artistic influences and ritual practices. Moving from chapter to chapter, cave to cave, readers and viewers will come to discover that there is no one or right way to approach Dunhuang.

No matter how many times she visits the caves, writes Rutgers University art history professor Annette Juliano, they continue to stimulate and surprise her. On one trip she was struck by a colossal icon of the bodhisattva Maitreya preaching in Tushita Heaven, perfecting his wisdom and waiting to descend to earth just as Shakyamuni had done. Reflecting on the future buddha, Juliano builds a bridge between the past and present. Her study on textiles, thrones, and crowns, like others in the volume, demonstrates how certain motifs participated in the “dynamic, complex, and sometimes mysterious processes” by which ideas and images were transmitted and assimilated.

The Mogao Caves have re-emerged as a popular travel destination, and they now face unprecedented levels of stress.

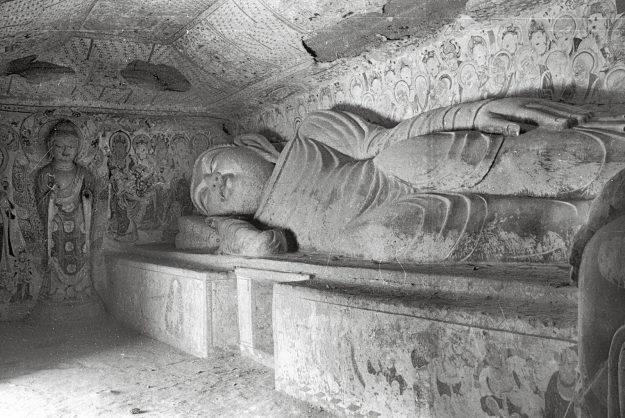

In another essay, Cary Liu, a curator at the Princeton University Art Museum, takes a step back to look at Dunhuang as a living ecosystem. Itinerant monks, pilgrims, merchants, and craftsmen regarded the landscape as magically alive, brimming with protective and malevolent spirits. Considered a localized home for buddhas and other divine beings, the desolate terrain and nearby peaks, notably Mount Sanwei, often served as the backdrop for mystical and visionary experiences, and there are testimonies of miracles taking place in the area. It is no wonder, then, that many of the sanctuaries were used as retreat quarters by Buddhist monastics throughout the ages. Other niches, like the chamber with a massive reclining Buddha in parinirvana dated to the 9th or 10th century, were constructed to accommodate larger gatherings, likely for teachings.

Wei-Cheng Lin, an architectural historian at the University of Chicago, isn’t as concerned with how these were built (for more on that you can refer to eminent sinologist Roderick Whitfield’s chapter). Instead, he investigates how cave architecture mediated meditative practices and certain ritual movements such as circumambulation. For practitioners, Lin suggests, entering the caves was like entering a Pure Land, allowing them to come face-to-face with a buddha. But getting there was certainly not for the fainthearted. When he visited Dunhuang at the turn of the 5th century, the well-known Buddhist monk-translator Faxian summed up the daunting approach in his travelogue: “As far as the eye can see, no road is visible across the desert, and only the skeletons of those who have perished there serve to mark the way.”

After centuries of abandonment, the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang have re-emerged as a popular travel destination. In modern times, however, the caves face unprecedented levels of stress, with foot traffic surpassing the one-million mark each year. Situated within fragile microclimates, the murals are extremely vulnerable to fluctuations in moisture and carbon dioxide. Ambient humidity, exacerbated by a constant flow of visitors during the hot summer months, can cause salts in the plaster walls to liquify. In several caves, this process has led to frescoes detaching from the underlying rock, resulting in irreparable damage. Because the complex also lies in an earthquake-prone zone, conservators like Neville Agnew of the Getty Conservation Institute say that measures must be taken now to protect against further erosion and collapse. Another ongoing issue is unfortunately glossed over in the book: custody battles over antiquities stolen from Asia and looting at Dunhuang in particular. The Harvard Art Museums, for example, have struggled with whether to repatriate their collection of Tang dynasty murals that were peeled off the Mogao Caves’ walls in the 1920s by Langdon Warner, the American archaeologist and Asian art scholar thought to have been one inspiration for Steven Spielberg’s tomb raider, Indiana Jones.

Countless questions remain about the caves’ past lives as well as their future. Can we ever come to know and understand a place as vast and sacred as Dunhuang? Perhaps, but we certainly can’t do it by ourselves, let alone in a single lifetime. Chances are that the Los didn’t have the faintest idea they were starting something that would continue long after they were gone. And yet the decades of scholarship, international partnerships, and conservation initiatives they’ve catalyzed have brought us closer to reconstructing the past and have driven us to become more diligent stewards of it. These living histories may still be incomplete, but they are far more comprehensive than anything we could attempt on our own.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.