In the first installment of Jack Kerouac’s previously unpublished life of the Buddha (Vol. I/, No.4), we learned of Siddhartha’s protected upbringing within the palace walls, his marriage at age sixteen to Yasodhara, and the birth of his son, Rahula. We also learned that at the age of twenty-nine, after encountering suffering in the form of old age, sickness, and death, he bid farewell to his wife and son, saddled his horse in the middle of the night, and left the palace in pursuit of a spiritual life. In this, the second of eight episodes to be published in Tricycle, we pick up the story after the young prince has shorn his hair, traded his clothes for those of a beggar, and vowed homelessness. The full manuscript will be published in Some of the Dharma by Viking Penguin in 1995. Note: All of Kerouac’s original spellings and usage have been retained.

HE MADE INQUIRIES and roamed along looking for the famous ascetic, Alara Kalama, whom he’d heard so much about, who would be his teacher. Alara Kalama expounded the teaching called ‘the realm of nothingness,’ and practised self-mortification to prove that he was free from his body. The young new Muni of the Sakya clan followed suit with eagerness and energy. Later, to his disciples he recounted these early experiences of a self-mortifyer. “I fed my body on mosses, grasses, cow-dung, I lived upon the wild fruits and roots of the jungle, eating only of fruit fallen from the trees. I wore garments of hemp and hair, as also foul clouts from the charnel house, rags from dust heaps. I wrapped my nakedness with lengths of grass, bark and leaves, with a patch of some wild animal’s mane or tail, with the wing of an owl. I was also a plucker out of hair and beard, practiced the austerity of rooting out hair from head and face. I took upon myself the vow always to stand, never to sit or lie down. I bound myself perpetually to squat upon my heels, practiced the austerity of continual heel-squatting. A ‘thorn-sided-one’ was I; when I lay down to rest, it was with thorns upon my sides—I betook myself to a certain dark and dreadful wood and in that place made my abode. And here in the dense and fearsome forest such horror reigned, that the hair of whomsoever, not sense-subdued, entered that dread place, stood on end with terror.” For six years with Alara Kalama and later the five mendicant hermits near Uruvela in the Forest of Mortification he who would become the Buddha practised these useless and grisly exercises together with a penance of starvation so severe that “like wasted withered reeds became all my limbs, like a camel’s hoof my hips, like a wavy rope my backbone, and as in a ruined house the rooftree rafters show all aslope, so sloping showed my ribs because of the extremity of fasting. And when I touched the surface of my belly my hand touched my backbone, and as I stroked my limbs the hair, rotten at the roots, came away in my hands.”

FINALLY ONE DAY in trying to bathe in the Nairanjana he fainted in the water and almost drowned. He realized that this extreme method of finding salvation was just another form of pitiful ignorance; he saw it was the other side of the coin of existence that on one side showed extreme lusting, the other extreme fasting; extreme luxurious concupiscence and sense-ennervation on the one hand, dulling the heart of sincerity, and extreme impoverished duress and body-deprivation on the other hand, also dulling the heart of sincerity from the other side of the same arbitrary and cause-bedighted action.

“Pitiful indeed are such sufferings!” he cried, on being revived by a bowlful of rice milk donated to him by a maiden who thought he was a god. Going to the five ascetic hermits he preached at last: “You! to obtain the joys of heaven, promoting the destruction of your outward form, and undergoing every kind of painful penance, and yet seeking to obtain another birth—seeking a birth in heaven, to suffer further trouble, seeing visions of future joy, while the heart sinks with feebleness . . . I should therefore rather seek strength of body, by drink and food refresh my members, with contentment cause my mind to rest. My mind at rest, I shall enjoy silent composure. Composure is the trap for getting ecstasy; while in ecstasy perceiving the true law, disentanglement will follow.

“I desire to escape from the three worlds—all earth, heaven and hell. The law which you practice, you inherit from the deeds of former teachers, but I, desiring to destroy all combination, seek a law which admits of no such accident. And, therefore, I cannot in this grove delay for a longer while in fruitless discussions.”

The mendicants were shocked and said that Gotama had given up. But Sakyamuni, calling their way “trying to tie the air into knots,” ceased to be a tapasa self-torturer and became a paribbijaka wanderer.

Wayfaring, he heard of his father’s grief, after six years so keen, and his gentle heart was affected with increased love. “But yet,” he told his newsbearer, “all is like the fancy of a dream, quickly reverting to nothingness . . . Family love, ever being bound, ever being loosened, who can sufficiently lament such constant separations? All things which exist in time must perish . . . Because, then, death pervades all time, get rid of death, and time will disappear. . .

“You desire to make me king . . . Thinking anxiously of the outward form, the spirit droops. . . The sumptuously ornamented and splendid palace I look upon as filled with fire; the hundred dainty dishes of the divine kitchen, as mingled with destructive poisons. Illustrious kings in sorrowful disgust know the troubles of a royal estate are not to be compared with the repose of a religious life. Escape is born from quietness and rest. Royalty and rescue, motion and rest, cannot be united. My mind is not uncertain; severing the baited hook of relationship, with straightforward purpose, I have left my home.

“Follow the pure law of self denial,” he preached on the road to other hermits. “Reflect on what was said of old. Sin is the cause of grief.” The glorious Ashvaghosha describes the Buddha, at this stage:

With even gait and unmoved presence he entered on the town and begged his food, according to the rule of all great hermits, with joyful mien and undisturbed mind, not anxious whether much or little alms were given: whatever he received, costly or poor, he placed within his bowl, then turned back to the wood, and having eaten it and drunk of the flowing stream, he joyous sat upon the immaculate mountain.

And he spoke to kings and converted them. “The wealth of a country is not constant treasure but that which is given in charity,” he told King Bimbisara of Magadha who had come to him in the woods asking why a man of royal birth should give up the advantages of rule. “Charity scatters, yet it brings no repentance.”

But the King wanted to know, Why should a wise man, knowing these valuable injunctions concerning rule, give up the throne and deprive himself of the comforts of palace life?

“I fear birth, old age, disease, and death, and so I seek to find a sure mode of deliverance. And so I fear the five desires—the desires attached to seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, and touching—the inconstant thieves, stealing from men their choicest treasures, making them unreal, false, and fickle—the great obstacles, forever disarranging the way of peace.

“If the joys of heaven are not worth having, how much less the desires common to men, begetting the thirst of wild love, and then lost in the enjoyment. Like a king who rules all within the four seas, yet still seeks beyond for something more, so is desire, so is lust; like the unbounded ocean, it knows not when and where to stop. Indulge in lust a little, and like the child it grows apace. The wise man seeing the bitterness of sorrow, stamps out and destroys the risings of desire.

“That which the world calls virtue is another form of the sorrowful law.

“Recollecting that all things are illusory, the wise man covets them not; he who desires such things, desires sorrow.

“The wise man casts away the approach of sorrow as a rotten bone.

“That which the wise man will not take, the king will go through fire and water to obtain, a labor for wealth as for a piece of putrid flesh.

“So riches, the wise man is ill-pleased at having wealth stored up, the mind wild with anxious thoughts, guarding himself by night and day, as a man who fears some powerful enemy.

“How painfully do men scheme after wealth, difficult to acquire, easy to dissipate, as that which is got in a dream; how can the wise man hoard up such trash! It is this which makes a man vile, and lashes and goads him with piercing sorrow; lust debases a man, robs him of all hope, while through the long night his body and soul are worn out.

“It is like the fish that covets the baited hook.

“Greediness seeks for something to satisfy its longings, but, there is no permanent cessation of sorrow; for by coveting to appease these desires we only increase them. Time passes and the sorrow recurs.

“Though a man be concerned in ten thousand matters, what profit is there in this, for we only accumulate anxieties. Put an end to sorrow then, by appeasing desire, refrain from busy work, this is rest.”

But King Bimbisara could not help remarking as Kandaka had done, that the Prince of the Sakyas was so young to renounce the world.

“You say that while young a man should be gay, and when old then religious, but I regard the fickleness of age as bringing with it loss of power to be religious unlike the firmness and power of youth.”

The old king understood.

“Inconstancy is the great hunter, age his bow, disease his arrows, in the fields of life and death he hunts for living things as for the deer; when he gets his opportunity he takes our life; who then would wait for age?”

And with respect to religious determination he counselled the king to stay away from the practice of sacrifices. “Destroying life to gain religious merit, what love can such a man possess? Even if the reward of such sacrifices were lasting, even for this, slaughter would be unseemly; how much more when the reward is transient! The wise avoid destroying life! Future reward and the promised fruit, these are governed by transient, fickle laws, like the wind, or the drop that is blown from the grass; such things therefore I put away from me, and I seek for true escape.”

The king realized that his understanding was more important than his wealth, because it came before. He thought: “May I keep the law, the time for understanding is short.” He became an enlightened ruler and the lifelong supporter of Gotama.

Gotama conducted learned discussions with hermit leaders in the forest. Of Arada U darama he asked: “With respect to old age, disease, and death, how are these things to be escaped?”

The hermit replied that by the “I” being rendered pure, forthwith there was true deliverance. This was the ancient teaching propounding the Immortal Soul, the “Purusha,” Atman, the Oversoul that went from life to life getting more and more or less and less pure, with its final goal pure soulhood in heaven. But the holy intelligence of Gotama perceived that this “Purusha” was no better than a ball being bounced around according to concomitant circumstances, whether in heaven, hell, or on earth, and as long as one held this view there was no perfect escape from birth and destruction of birth. The birth of any thing means death of the thing: and this is decay, this is horror, change, this is pain.

Spoke Gotama: “You say that the ‘I’ being rendered pure, forthwith there is true deliverance; but if we encounter a union of cause and effect, then there is a return to the trammels of birth; just as the germ in the seed, when earth, fire, water, and wind seem to have destroyed in it the principle of life, meeting with favorable concomitant circumstances, will yet revive, without any evident cause, but because of desire, and just to die again; so those who have gained this supposed release, likewise keeping the idea of’!’ and living things, have in fact gained no final deliverance.”

Approaching now his moment of perfection in wisdom and compassion the young Saint saw all things, men sitting in groves, trees, sky, different views about the soul, different selves, as one unified emptiness in the air, one imaginary flower, the significance of which was unity and undividable-ness, all of the same dreamstuff, universal and secretly pure.

He saw that existence was like the light of a candle: the light of the candle and the extinction of the light of the candle were the same thing. He saw that there was no need to conceive the existence of any Oversoul, as if to predicate the entity of any ball, to have it be bounced around according to the winds of the harsh imaginary March of things, and all of it a mind-made mess, much as a dreamer continues his nightmare on purpose hoping to extricate himself from the frightful difficulties that he doesn’t realize are only in his mind.

GOTAMA SAW THE PEACE of the Buddha’s Nirvana. Nirvana means blown out, as of a candle. But because the Buddha’s Nirvana is beyond existence, and conceives neither the existence or non-existence of the light of a candle, or an immortal soul, or any thing, it is not even Nirvana, it is neither the light of the candle known as Sangsara (this world) nor the blown-out extinction of the candle known as Nirvana (the no-world) but awake beyond these arbitrarily established conceptions.

He was not satisfied with Arada’s idea of the “I” being cleared and purified from heaven. He saw no “I” in the matter. Nothing to be purified. And covetise of heaven nothing but activity in a dream. He knew that when seen from the point of view of the true mind, all things were like magic castles in the air.

“What Arada has declared cannot satisfy my heart. I must go and seek a better explanation.”

Gotama was about to find that explanation. As an eminent writer said: “He has sought for it in man and nature, and found it not, and lo! it was in his own heart!”

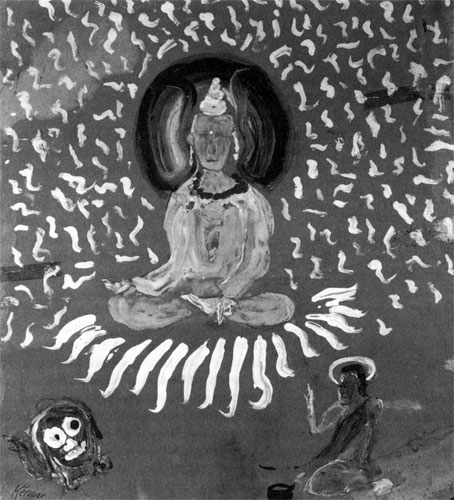

THE BLESSED HERMIT went to Budhgaya. At once the ancient dream of the Buddhas of Old possessed him as he gazed at the noble groves of palm and mango and ficus religiosa fig trees; in the rippling afternoon he passed beneath their branches, lonely and bemused, yet with a stirring of premonition in his heart that something great was about to happen here. Gotama the “founder” of Buddhism was only rediscovering the lost and ancient path of the Tathagatha (He of Suchnesshood); re-unfolding the primal dew drop of the world; like the swan of pity descending in the lotus pool, and settling, great joy overwhelmed him at the sight of the tree which he chose to sit under as per agreement with all the Buddha-lands and assembled Buddha things which are No-things in the emptiness of sparkling intuition all around like swarms of angels and Bodhisattvas in mothlike density radiating endlessly towards the center of the void in ADORATION. “Everywhere is Here,” intuited the saint. From yonder man, a grass cutter, he obtained some pure and pliant grass, which spreading out beneath the tree, with upright body, there he took his seat; his feet placed under him, not carelessly arranged, moving to and fro, but like the firmly fixed and compact Naga god. “I WILL NOT RISE FROM THIS SPOT,” he resolved within himself, “UNTIL, FREED FROM CLINGING, MY MIND AITAINS TO DELIVERANCE FROM ALL SORROW.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.