This issue’s special section, Dharma, Diversity, and Race, suggests that little dialogue exists among Asian-American Buddhist communities, and between those communities and Americans new to Buddhism. Not coincidentally, in the very absence of dialogue lies the heart of the question: is the unfolding of Buddhism in this country evolving into something called “American Buddhism”; and if so, does the “American” part of that accurately represent the multicultural diversity of Buddhists in America, or is it simply another projection of the white majority?

Multiculturalism in the United States exists in a context defined by two factors: actual white racism, and the idealized, constitutional promise of racial equality. This contradiction provides an axis around which America continually reinvents itself: witness, for example, a nation eager to know how “the race card” will be played in the O. J. Simpson trial.

The challenge now faced by the United States is how to respect and enjoy racial, religious, and cultural distinctions without contributing to the kind of fragmented fervor that could leave this country looking like Bosnia. The challenge faced by Buddhists is to see how the Buddha’s insights apply to multiculturalism—a daunting opportunity, for applying the Buddhist path of liberation to the suffering of racism tests both the commitment to a living breathing Buddhism as well as to those timeless truths that know no borders. Whether or not this attempt reflects “American Buddhism” or “Buddhism in America” is not a particularly interesting question; yet wrestling with these issues—exploring the outer and inner edges of freedom, liberation, emancipation—has a history and a language and an urgency that is specific to this place and to this time.

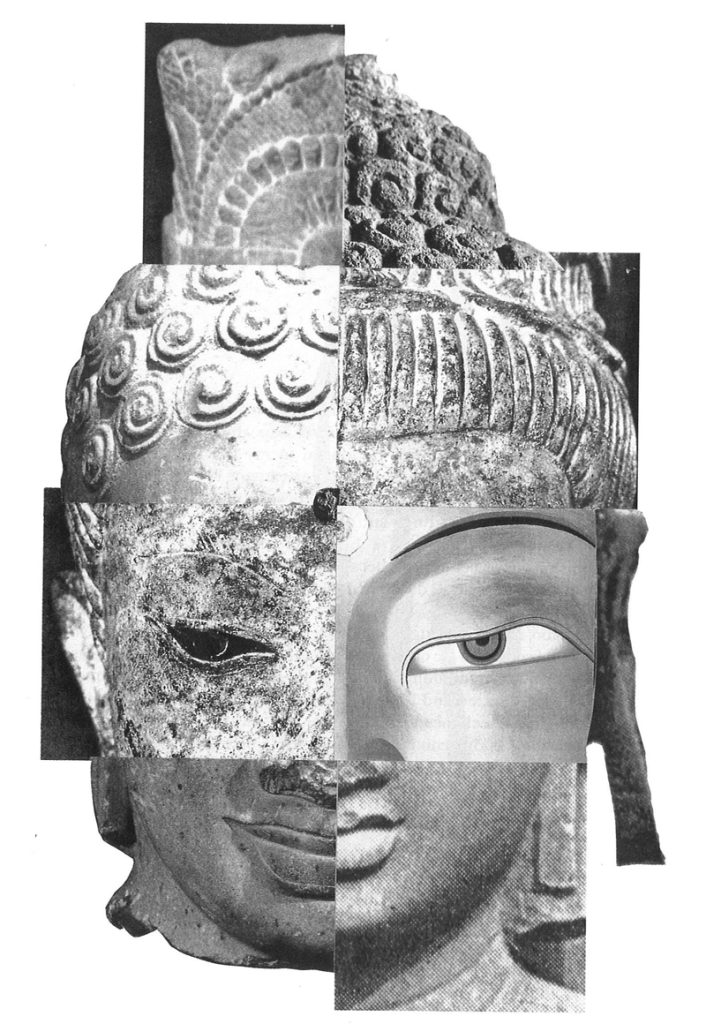

The concept of freedom in this country was defined with the American Revolution, with freeing the colonies from British rule. However historic, and noble an effort, the Revolution of 1776 did not transcend its own times enough to include African slaves. Their emancipation would, on paper, come with the Civil War. Shakyamuni Buddha’s revolution was without warfare; without provoking violent opposition, he defied prevailing Brahmanic conventions to teach not only rulers and wealthy merchants but outcasts, the disinherited, street punks, even—eventually—women. He then went on to guide his diverse followers on the path of liberation. In the Buddha’s teachings, the source of absolute liberation is internal, a state of mind that is not dependent on external circumstances, not on race, class, or gender. In dharma, democracy is the birthright of our own Buddha-nature—the democracy of being that goes beyond all culture, all concepts.

Jean-Paul Sartre said, There are two ways to enter a gas chamber: free and not free. Yet this reality cannot be used to exonerate Hitler. In the same way, the possibility for a person of color to attain spiritual liberation in a racist society cannot be used to relinquish social responsibilities, nor to justify prejudice. Yet if the possibility of absolute liberation is forfeited for the sake of social justice, then Buddhism has little new to offer the Western heritage of social responsibility and liberal humanism.

The Buddhist path is designed to reveal ever deeper levels of reality. We live in a pluralistic society. We live in a racist society, a homophobic and sexist society; in addition, Buddhists of every color, each gender, and all sexual orientations embrace the sectarian prejudices that developed in Asia. We live in a society that is pleading for us to put our shoulders to the wheel. We are also, each and everyone of us, whole and perfect as is, interrelated, essentially non-separated, and equal. This too, must be realized. If we forsake the inside for the outside, it is not just Buddhism that is diminished but the horizons for true social transformation as well.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.