As an artist and dharma student, I’ve always felt a deep connection to, and appreciation for, the calligraphy of the Japanese Zen masters. Initially I thought that Chinese Calligraphy (Yale University Press, 2008, $75.00 cloth), edited by Ouyang Zhongshi and Wen C. Fong, and translated by Wang Youfen, would cover familiar ground. In fact, it explores mostly new territory.

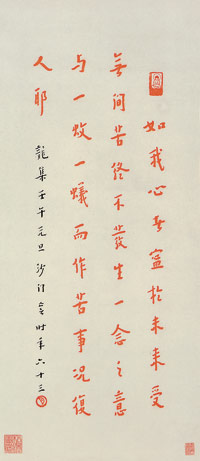

Buddhist Vow in Running-Standard Script, Hongyi (Li Shutong) 1942, hanging scroll, cinnabar ink on paper ©Smithsonian Institution

In China, calligraphy has long been considered the highest form of art, one both utilitarian and expressive. Ten years in the making, Chinese Calligraphy represents the combined efforts of fourteen scholars. A monumental book with over 500 pages and 600 illustrations, it covers the theoretical, cultural, and artistic aspects of calligraphic expression from the second century to the present.

Beyond its value as a survey of the art, the book provides a sweeping view of Chinese history, illuminating how closely the various forms of calligraphy were tied to the prevailing political and cultural mores of each dynastic period. Calligraphy has been practiced in China by hermits and government officials alike—I had no idea, for instance, that both Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong were practitioners of considerable, if eccentric, talents—and the book is peppered with stories of calligraphic superstars such as Mi Fu (1051–1108), also known as “Mi the Crazy,” and Huang Tingjian (1045–1105), who once noted that watching people rowing a boat helped him improve his brushwork.

The spiritual and mystical aspects of calligraphy are covered in the context of Confucianism, and Buddhist and Taoist philosophy. Just as each brush stroke leaves a trace of its maker, each character is thought to store the maker’s power. As a non- Chinese-speaking reader, I wasn’t privy to what these calligraphic texts are saying. Nevertheless, I found their visual impact considerable, and titles such as “Poem About Ink” hint at a world both commonplace and magical. As a Buddhist practitioner, I was particularly drawn to a rendering of the Heart Sutra (1340) and one of a Buddhist vow (1942) (see right). Chinese Calligraphy is daunting at first but rewards the reader with a wealth of information and images of extraordinary beauty

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.