As you drive through the smoggy San Gabriel Valley on Highway 60, you crane your neck as you reach Hacienda Heights, the locale of the Hsi Lai Buddhist Temple. Though a concrete wall buffers the temple from the freeway, you see a glint of sweeping yellow roofs and you know that soon you’ll arrive there. The Saturday vegetarian brunch that’s served will fill your stomach, but what you’re seeking is enlightenment on some of the issues surrounding the 1996 Democratic fundraising debacle in which the temple and its Buddhist clergy and nuns were prominently fingered.

You’d already talked to a few Asian friends about the situation. One Beijing writer, Huang, here in the States for the last seven years, remarked: “I think they were picked on more because they were Asian rather than Buddhists. On the other hand, the combination of Asian plus Buddhism equals exotic. What about the Christians who donated to the right wing or the Republicans?”

I asked him what he thought of the Hsi Lai Temple. “Too big. Too secular. It seems mainly for Taiwan immigrants.” Sabina, another friend, a Taiwanese urban planner living in Los Angeles, felt that U.S. ethnic politics—not religious politics—determined both community and media response. She considered herself an “unofficial Buddhist” though she didn’t attend temples regularly.

You climb up the first set of stairs to the courtyard of the main pavilion, where Chinese, Vietnamese, and other Asian devotees and tourists gawk at the large statues of assorted Bodhisattvas, Kwan-yins, and traditional animals such as deer, dragons, and turtles. While you can see that the temple obviously had enough funds to build its elaborate temple, schools, and housing for clergy and nuns, you don’t get a sense of lingering corruption or undue entrepreneurship. At this point, you’re not prepared to pass judgment. You’re prepared to be compassionate or at least empathetic with what you find.

You recall the broad outlines of the case: Media obsession with the 1996 Democratic campaign finance debacle had resulted in over 4,000 articles in newspapers and magazines on the topic between 1996 and 1998. Although two Asian American donors, John Huang and Charles Trie—both connected with the Democratic National Committee and the reelection of Clinton—were centrally involved, two Buddhist nuns from Southern California were charged and indicted on charges of criminal contempt on April 5, 2000, just months ago. The two women, Yu Chu and Man Ho, were charged with fleeing to Taiwan to avoid testifying at the trial of Los Angeles immigration consultant Maria Hsia. Hsia had been convicted on five felony counts related to her role in the Hsi Lai Buddhist Temple fund-raising event attended by Vice President Al Gore four years ago. Both nuns were connected with the Hsi Lai Temple: Yi Chu was the temple treasurer, and Man Ho was the administrative officer.

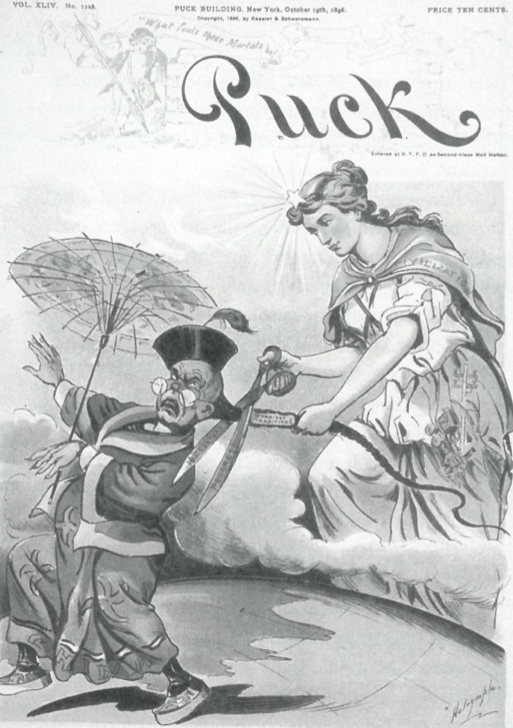

The Buddhist temple fund-raising case revolved around an alleged scheme in which dozens of foreign donors were reimbursed for political contributions to the 1996 reelection campaign of Gore and Clinton. Almost all of the $100,000 netted was later returned by the Democratic National Committee. Although John Huang raised $3.5 million out of the total $2.2 billion raised in the 1996 federal elections, the “Asian connection” and the allegation of a Communist Chinese plot to influence U.S. politics garnered 90 percent of the media attention. The Democrats and Republicans both abetted and distanced themselves from the scandal, which seriously challenged and concerned Asian Americans across the nation.

So you ask yourself—haven’t these Buddhists been the unfair target of politicians and media pundits? But is it because they are Buddhist—or because they are Asians in America? Or is it the unfortunate combination of both? Suppose, you ask yourself, they were non-Asian, white Buddhists who had been accused of doing the same thing? The media would not have made a big deal about it—or linked the Asians to Asia or to xenophobic allegations of “Red Chinese” spying or influence. But the Republicans saw a window of opportunity—as they’ve always done—to confound the status and history of Asians . . . those from Asia, as well as local U.S.-born or naturalized Asian Americans whose cultural and political allegiances are to America. Obviously, John Huang and Charles Trie represented the post-1975 transnational business class of Asians who have had nothing to do with local Asian American politics (e.g., school boards, Chinese historical societies, Asian American Studies). As Asian Americans, we were foolish to even attempt to defend them.

Yet on the other hand, some of us, as Buddhists in America, should have raised more fundamental issues concerning the case—and the moral caliber of those who made up the Democratic and Republican Party tickets. Are they compassionate, in tune with the precepts of the Buddha, possessing visions and ideas around racial and human rights, labor and justice issues, and about war and peace? Do they reveal compassion in their words and actions? Should we not speak out, as Buddhists, about these candidates? Or should we let ourselves be bound by the two-party system, by the Republicans and Democrats, and the impoverished visions they put out to the media like stale bread?

I could go on to say that what bothers me is a poverty of thought, a corruption of morality, and a lack of righteous words. But then, shouldn’t I look at myself and my lack of speaking out on these more fundamental issues? Ultimately, the question might be: Were Buddhists being singled out for prosecution? Yes and No. “Yes,” because they were Asian they were singled out. “No,” not because they were Buddhists. But “yes” again, because they were not white Buddhists. In another sense, it’s important to realize how long-standing American xenophobia toward Asians, toward immigrants, towards foreigners—compounded with homegrown racism—could result in suspicion, fear, and ultimately prosecution of Asian Buddhists in America. After all, Asian immigrants from the nineteenth century onward were the “yellow peril,” their citizenship denied up until World War II. American-born, naturalized, or immigrant, Asians in America are still perceived as “foreigners” to this day. In fact, Japanese Buddhist priests were among the first to be rounded up during the World War II forced internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans in desert concentration camps. Sixty years later, a fifth-generation Japanese American can still be approached by a white person on the streets of L.A. and asked, “Do you speak English?” And, most likely this is followed by, “But you speak so well!”

A San Francisco activist, academic, and media watchdog, Professor Ling-chi Wang of U.C. Berkeley, said about the racialization of potential corruption: “The most direct benefit from racializing political corruption by both political parties is the diversion of public attention from the crisis facing American democracy. Instead of addressing the systemic problem of money corruption in politics, politicians discovered the perfect distraction: Blame the problem on Asian Americans and the unscrupulous ‘spies’ or ‘agents’ of ‘communist’ China.”

Corruption. Communism. Compassion. Is there a thread that travels, however awkwardly, through these three concepts? As Americans and as Asian American Buddhists who participate in civil society, we need to better link our beliefs with our practices. Compassion needs to be translated into political activism, whether by speaking out, writing a leaflet or pamphlet, or testifying as citizens with regard to our beliefs concerning nativism or xenophobia as directed toward nonwhites, immigrants, undocumented workers, and various boat peoples. Compassion and activism need to be extended toward such real issues as abuse and violence toward women, children, and gays and lesbians. Inequalities in medical and health care, housing, and education loom even larger in the face of the U.S. globalization and capitalism that widen the divide between the haves and the have-nots. Indeed, communism is hardly a threat, and we should reexamine socialist humanism from new, utopian perspectives.

As Buddhists, it is never possible to merely “sit” and wait to redeem our own souls. Buddhism and politics have always been intertwined, and that linkage is here to stay. We’re on this frenzied wheel of corruption together, Asians, Asian Americans, and Americans of all stripes and colors.

I reverse gears, turning back against the yellow-tiled roofs of the temple, and drive back into the city of samsara and smog—Los Angeles.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.