It is the day for takuhatsu in Olympia, this small city in the State of Washington. After zazen and morning ceremony, we eat a modest breakfast of oatmeal and tea and still feel hungry. This is good, as one should not go begging on a full stomach. The rain has held off, but it is misty, windless, and raw. Streets and alleys are full of puddles. Only students who have requested this opportunity are participating, and two are doing takuhatsu for the first time. There will just be four of us. We are not trying to create a spectacle; we are practicing a tradition of Zen that dates to the time of Shakyamuni Buddha and has been passed down with the begging bowl to the lineages of the present day.

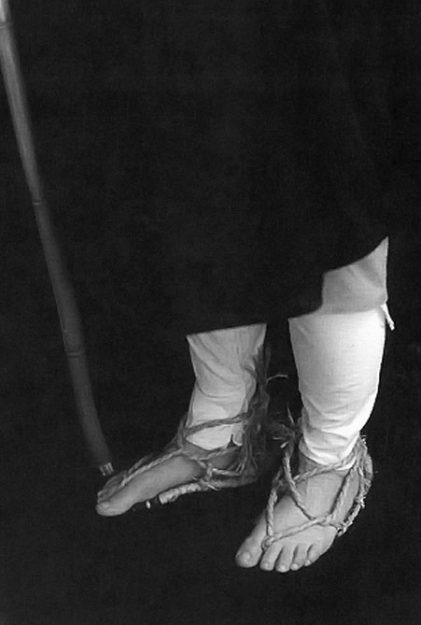

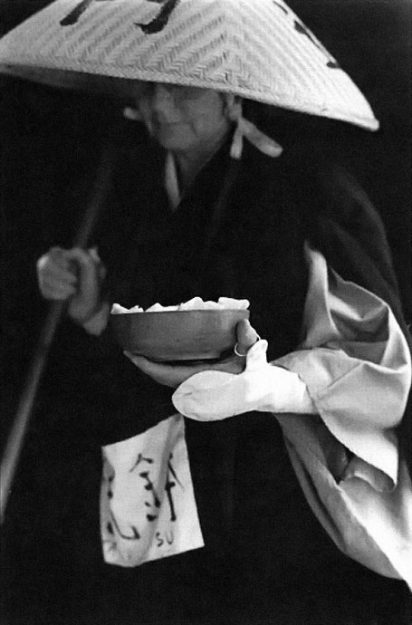

I am a priest and trained at Entsuji temple in Japan, where Ryokan (l758-1831), the poet, priest, and hermit, trained before embarking upon a life outside the monastery, totally dependent on takuhatsu. Takuhatsu brings the monastery directly into the marketplace. On the alms-round, I wear the traditional takuhatsu clothing of the monk: kimono and horomo hiked up and tied at the waist so that the white cloth leggings show below the knee; half-gloves covering the visible portion of the forearm; towel around the head to keep the wide straw woven hat from slipping; grass sandals over tabi, the Japanese socks with the big toe separated from the other toes, like mittens. Students wear their street shoes and standard Japanese temple work clothing to clearly identify them with our temple. They will also wear arahusu, the “little robe,” and a takuhatsu bag to collect offerings and display our affiliation, Olympia Zen Center. We all carry begging bowls. I also carry a tall stick with three rings on top that will make a clear ching-ching as it taps along the pathway, leading the procession.

Takuhatsu is one of the deepest traditions of my Soto Zen lineage. We recognize the influence of Ryokan, who spent his life in solitude and utmost simplicity, writing poems and painting, teaching through the example of kindness and goodwill, relying only on the fruits of takuhatsu for his food and sustenance. It was along the narrow streets near Entsuji that the sound of Ryokan-san’s begging stick first rang out against the mud walls of the old farm buildings. Later he returned to his hometown and wandered from there throughout the Bunsui plain, living as a mendicant. The tradition of takuhatsu remains unbroken in Japanese Zen.

Begging is legal in Olympia as long as one does not engage in aggressive panhandling. “Panhandling,” an American colloquialism borrowed from the homeless, literally refers to the use of a pan with a handle for begging. In the United States, religious begging has all but disappeared. Years ago, members of the Salvation Army, the last of the street religious beggars, would come out at Christmas with their unmistakable Army bells as shoppers entered the supermarket. As late as the 1950s, religious organizations practiced begging on city streets in the State of New York. They went from door to door, or stood at train stations or outside factories, accepting donations. This was acceptable and recognized as virtuous practice. As begging became popular—though not completely acceptable—during the hippie movement of the late 1960s, young people took to America’s streets, demonstrating the need for changing values in society. They did not hesitate to ask for money, and people were curious and generally responsive. That era ended with an increase in homelessness, and as the homeless population grew, the practice of begging persisted and the public became impatient with the continuing visibility of the poor. Other areas were beset by members of the Hare Krishna movement, who had aggressive and confrontational methods. Some cities passed ordinances to prevent beggars from annoying people. Begging is now illegal in some parts of the United States and restricted elsewhere.

Few religious groups practice poverty today in the manner of Ryokan, or even in that of St. Francis of Assisi, who taught his monks to store no more food than they could use for one day. At the same time, begging has been institutionalized in the form of fund-raising, conducted by every church and nonprofit corporation in America. Giving is no longer a direct transaction from the donor to the begging bowl. Americans make appeals through the mail requesting donations for every imaginable cause. If donors are moved, they send a check. There is no contact, no communal prayer, no immediate direct eye-to-eye gesture.

I was raised in a begging tradition. During my childhood in Brooklyn in the 1940s and’ 50s, the Great Depression was still a recent enough memory for most people to appreciate that begging had once been commonplace. Catholic monastics practiced begging, and it was not unusual to see clerics sitting outside shops holding coffee cups to collect coins. On Thanksgiving, children would dress up in old, torn clothing and go from door to door to beg. The practice reminded householders that kindness to beggars, especially on such a holiday, was virtuous, and it taught children that all people were worthy of notice and that sharing goods was the right thing to do.

I was raised in a begging tradition. During my childhood in Brooklyn in the 1940s and’ 50s, the Great Depression was still a recent enough memory for most people to appreciate that begging had once been commonplace. Catholic monastics practiced begging, and it was not unusual to see clerics sitting outside shops holding coffee cups to collect coins. On Thanksgiving, children would dress up in old, torn clothing and go from door to door to beg. The practice reminded householders that kindness to beggars, especially on such a holiday, was virtuous, and it taught children that all people were worthy of notice and that sharing goods was the right thing to do.

Because I had come of age in that milieu, takuhatsu seemed natural to me. I practiced Zen for many years in California with Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi before traveling to Japan to teach English. One day I wandered into Entsuji temple. The abbot, Niho Roshi, saw me in the garden and invited me in. At that moment, my practice of takuhatsu began.

In Olympia, just as at Entsuji, before leaving the zendo we face one another in a line and chant Hannya Shingyo, the Heart Sutra. We open the door and emerge into the cold winter air, and feel a sudden vulnerability. There is no hiding, no way to disguise what we are doing. We are suddenly visible to everyone. Feelings of joy at the opportunity to carry on a deep tradition, fear that we will be ridiculed and misunderstood, courage to go out and practice, trepidation in the face of our physical vulnerability, all mingle with the wisps of fog that catch around our ears as we walk in single file. A little more chanting and then down the hill into town we intone a deep “Hooooooooooooo,” which means “the rain of dharma,” and it echoes from the belly in a long vibrating stream. Our breathing is staggered and the echo is continuous. Cold hits the hand, and the fingers numb around the bowl.

As far as we know, no Zen communities in America are practicing takuhatsu in this particular ancient form. Our sangha has had long discussions about why, although it was practiced and taught by Shakyamuni Buddha and all Zen monks since, takuhatsu has not been transmitted to America. Why is it that Americans have embraced zazen meditation and yet do not incorporate takuhatsu in their practice? Even many Japanese teachers say, “Takuhatsu is impossible for Americans.” They may have been reticent to transmit the practice in America for several reasons. We are a violent nation; Americans are outspoken and don’t hesitate to belittle or ridicule what we don’t understand. In takuhatsu, there is no cover from the dangerous, the rude or obscene. Japanese teachers may have seen the practice as too controversial, too problematic outside their own culture, and felt that to establish it at all, takuhatsu had to be acceptable to society. It had to find its way into the mainstream of daily life.

Although we hold the bowl open for an offering, the practice of takuhatsu does not teach us to be dependent upon society, asking for something that is not earned, or pressuring a community for an entitlement to food or goods. Rather, it teaches us the fundamental lessons of the Buddha: to be dependent on everyone, to live our original homelessness, to include the homeless in thought and deed, to share everything, to accept what comes to us, to be generous, to be humble in society, to recognize the timid, to resist fame, to be modest, to resist the acquisition of goods, to throw off ego, to have the courage to be fully visible in practice.

We reach the main road and its heavy traffic. Pedestrians see us and stare. Our begging bowls are held out in one hand, the other held under the arakusu, eyes cast down. We cross the streets with the traffic lights and pass in front of motorists who now see us head-on. The insistent ching-ching of the stick keeps us concentrated: we are a living sangha, moving in a single body through the city.

Our first direct encounter is at Bread and Roses, the Catholic Worker soup kitchen. About ten men are gathered on the sidewalk talking as we turn the corner and walk toward them. We appear as a small attack force arriving out of nowhere. There is no precedent for this, no picture that they can turn to for reference. We are moving at a moderate pace, chanting Enmei Jihhu Kannon Gyo, the Kannon Sutra of Timeless Life, a devotion to Avalokiteshvara, the same prayer chanted at Entsuji temple and by Ryokan. The men on the street are facing us and staring. This is their block, their territory, and many who are standing here now will be begging later in front of various shops or huddling in the doorways of businesses that have closed for the weekend. Shopkeepers will ask them to move, saying they are bad for business and that they keep shoppers away.

I look out from under the hat, and my eyes meet one man’s eyes. His are deep, tired, and watery from the cold. His look is questioning, but in an instant we both recognize something: the takuhatsu I am doing is engaged in prayer; his begging is a raw kind of desperation that fights back incessant hunger and cold. I can go home and shower; he cannot. I have a place to sleep; he may not. We are exactly face to face. But though our material circumstances are indeed different, we are on the same ground; there is no difference in the essential truth of our humanity.

Our group is pulled along by the action of walking, by the silence of going forward step by step in our meditation. We try to give the man a paper that explains what we are doing, but he doesn’t want to take it. He shakes his hand and his head simultaneously. Finally, another man accepts. We go on our way.

Making money or filling the bowl in takuhatsu is not the point. The point is the practice of acceptance, humility, poverty. It addresses the arrogance of our material times. When we see that we are all homeless, we can fully exchange the meaning of this practice. Our giving away and our receiving are the same act. The spiritual gesture of takuhatsu reminds us where our true treasures lie and that the begging bowl and the hand filling it are always empty.

But coming to that realization on American ground is a path rife with questions and doubts, even for sincere practitioners. Because we live in an area populated by Christian fundamentalists, some followers fear that through takuhatsu we will be misunderstood, and to be misunderstood means to be discriminated against. Others speak of what it means to face the homeless or feel that by begging we might take what would otherwise be given to a homeless beggar. But perhaps the deepest, most debilitating notion—and one that hits the entire nation, not just those contemplating takuhatsu—is the terror of being perceived as, or associated with, the poor.

But coming to that realization on American ground is a path rife with questions and doubts, even for sincere practitioners. Because we live in an area populated by Christian fundamentalists, some followers fear that through takuhatsu we will be misunderstood, and to be misunderstood means to be discriminated against. Others speak of what it means to face the homeless or feel that by begging we might take what would otherwise be given to a homeless beggar. But perhaps the deepest, most debilitating notion—and one that hits the entire nation, not just those contemplating takuhatsu—is the terror of being perceived as, or associated with, the poor.

Takuhatsu is not about experiencing oneself as invisible to society in the sense of being unrecognized, overlooked, forgotten like the homeless, the poor or the aged. It is about realizing the “small” self as invisible. In the practice, we experience invisibility because the person we know by name—the usual daily self—is transformed; there is no one there to need to be noticed. It is the practice of liberation. Of course, we may be tempted to use takuhatsu as a spiritual masquerade, to enjoy accolades because of the exotic nature of the robes or the work. But sincere Zen practice is a mirror where attempts to inflate the ego are leveled again and again. We are brought to see the truth of ourselves—that ego itself is delusion.

Will takuhatsu take root in America? First, a visible monastic stream must flourish. While householder Zen takes hold, such practice must rest on a foundation where training and a clear understanding of dharma are solidly planted. In lay practice, we risk becoming a Sunday-only congregation, using the cushions occasionally but not when it interferes with the primary schedule of family life.

The Buddha lived as a mendicant, knowing that poverty—that is, a life of nonacquiring—is necessary to learn nonattachment and acceptance. The alms-round permitted the monks to practice poverty and humility, to overcome vanity. They also learned acceptance, since they were completely dependent upon what was offered, eating only what was put in the bowl, and only once a day. The disciple Makakasho is said to have eaten a leper’s finger that had dropped into his bowl, an extreme practice of indiscriminate acceptance. Ryokan ate food that had been shared by insects and grubs, going beyond discrimination of the condition of the food. The laity benefited through receiving the teachings the monks transmitted and gained merit through acts of generosity.

Later in the morning, we walk beside the marina and are photographed by a tourist against the backdrop of the State Capitol Building, a dome that is the copy of our capitol in Washington, D.C. We follow the boats to the farmers’ market, where we stand in one area for half an hour. One of us gives the handout to the curious, who walk slowly away, reading. Some, when they understand, return and make an offering. One man gives us a bagel that we later eat for lunch. Back at the zendo, we chant, wash our feet, and place the offerings on the altar. We drink tea, have lunch, feel the stiffness and soreness set into the muscles and joints. We begin to appreciate the life of a mendicant, the life of simplicity in poverty. Poverty: not an end in itself, but a means to a life in Buddha, complete and free.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.