Tricycle is pleased to offer the Tricycle Talks podcast for free. If you would like to support this offering, please consider donating. Thank you!

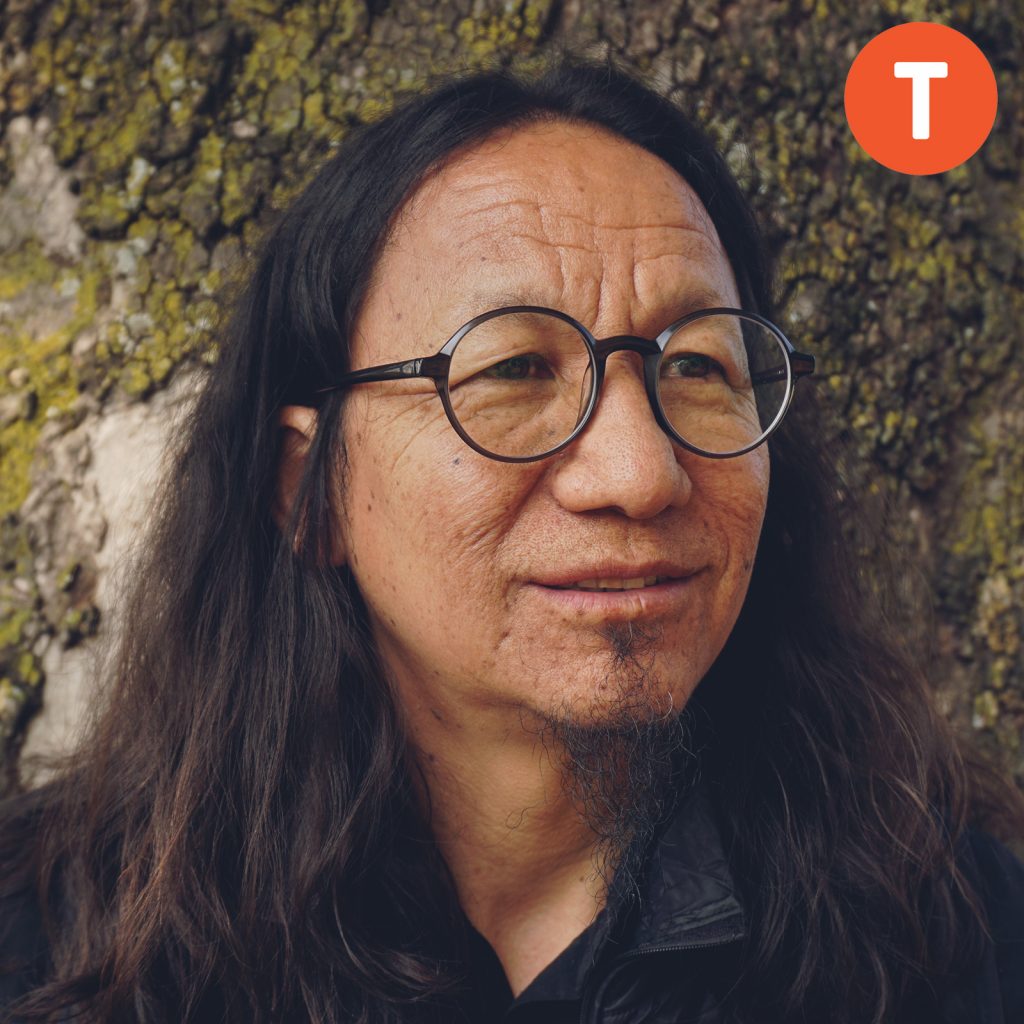

Bhuchung D. Sonam is an exiled Tibetan writer, poet, translator, and publisher currently based in Dharamshala. His press, TibetWrites, has published more than fifty books by contemporary Tibetan writers.

In this episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sits down with Sonam to discuss how writing has helped him navigate life in exile, the importance of centering the stories of ordinary Tibetans, why he views writing as a form of resistance, and how literature can serve as a bridge across cultures. Plus, Sonam reads a few of his poems.

Read Sonam’s review of the Dalai Lama’s latest book in the Fall 2025 issue of Tricycle.

Tricycle Talks is a podcast series featuring leading voices in the contemporary Buddhist world. You can listen to more Tricycle Talks on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, and iHeartRadio.

♦

We’d love to hear your thoughts about our podcast. Write us at feedback@tricycle.org.

Read transcript

Bhuchung D. Sonam: So we are less than 200,000 Tibetan refugees, and we are scattered over more than thirty different countries around the world, but our aspiration for a future Tibet must go on. So if we are to create this community of people who have some invisible connection, as far as how I look at it, I think art does that, and this is because the music that is produced from Tibet, we can hear living here in India, or anybody living in the US or Canada or Australia. Anywhere it can be heard. So I think this creates a kind of a community where we may not be together in one place, but still we are connected. I don’t know any other channel other than art forms that can do that and play that role. James Shaheen: Hello, and welcome to Tricycle Talks. I’m James Shaheen and you just heard Bhuchung D. Sonam. Bhuchung is an exiled Tibetan writer, poet, translator, and publisher currently based in Dharamshala. His press, TibetWrites, has published more than fifty books by contemporary Tibetan writers. In my conversation with Bhuchung, we talk about how writing has helped him navigate life in exile, the importance of centering the stories of ordinary Tibetans, why he views writing as a form of resistance, and how literature can serve as a bridge between cultures. Plus, Bhuchung reads a few of his own poems. So here’s my conversation with Bhuchung D. Sonam. James Shaheen: OK, so I’m here with Bhuchung D. Sonam. Hi, Bhuchung. It’s great to be with you. Bhuchung D. Sonam: Oh, thank you very much. Me too. James Shaheen: And thank you for your many contributions to Tricycle. Most recently, you reviewed the Dalai Lama’s latest book, and you just wrapped up celebrating His Holiness’s 90th birthday. So how did the celebrations go? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Oh, it went very well. There was a huge number of people, and a lot of rain as well, so it’s crowded and it’s wet in Dharmashala. Right now a lot of people are here from many different places, of course, and it’s almost the monsoon. July is monsoon here, so we get a lot of rain. The official birthday celebration ends today, so it’s been going on since July sixth. James Shaheen: Have you had a good time? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Oh, yes, very much indeed. James Shaheen: So Bhuchung, you’re a poet, you’re a writer, you’re a translator, you’re a publisher, and your press has published more than fifty books that center modern Tibetan voices. So before we get to your poetry, I’d like to ask you about your background. You say you grew up in a small village in Tibet with no access to books, and your primary form of entertainment was Ling Gesar stories. So can you tell us a bit about the stories you were exposed to as a child and how they influenced your approach to writing? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Yes. I was born in a very small village in central Tibet. It doesn’t fall on any of the major roads, so especially at the time I was in Tibet, it was very isolated. You know, we didn’t have books as such, especially when I was growing up in the early part of my life. But my grandfather, who was an abbot of the monastery, would take me with him to the mountains where he taught me how to read Tibetan. That’s how I learned to read Tibetan. And then later, probably in the early 1980s, probably in 1981, with China’s slight policy relaxation into Tibet, Ling Gesar stories started coming out, and somehow we had a neighbor who had a copy of one of Ling Gesar’s stories. He knew that I knew how to read, so although I was very young at the time, the family invited me to read that entire Gesar story. So that’s how I was initially introduced to stories. But of course, before that, in our village, we had a lot of elders who knew how to tell stories. So we had, for example, one old grandmother who used to tell a lot of Gesar stories. In fact, when I came into exile, I could remember one entire Gear story. Now, of course, I’ve forgotten. It’s been many decades. But that’s how I was introduced to stories and reading. James Shaheen: You say that you were taken into the mountains to learn to read Tibetan? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Mmhmm. Yeah. My grandfather was the abbot of the local monastery. Of course, after China’s occupation of Tibet, he became a shepherd of the community’s goats and sheep. So every morning he had to go to the mountain to graze the sheep and goats of the commune. In those days we had commune systems, you know, collective commune systems. So he was made the village shepherd. When I was very young, he used to take me along with him away from everybody in the mountains. You know, there were only the sheep and animals and me and grandfather. So, yeah, that’s how it happened. James Shaheen: Right. You mentioned that there was one elderly woman who, despite not being able to read or write, would enter storytelling trances every night. Can you say something about that? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Yes. You know, Ling Gesar stories are very oral. I think they originated orally. Even to this day, we have a lot of Gesar bards in Tibet. There was one very famous Gesar bard in eastern Tibet who could remember as many as 200 Gesar stories all from his memory. So I think that tradition is not only peculiar to Tibet, but also part of Ladakh and to some extent Mongol as well. So in our village, although that woman never knew how to read or write, she would, every evening, go into this storytelling mode, and then although in the daytime she would walk with a walking stick, once she went into that mode, she would jump and sing with a lot of gestures and facial expressions. So it was almost like a trance, I think. James Shaheen: Mmhmm. So you left Tibet in the winter of 1982 at the age of 11, and you say that in exile writing and literature became a salve to help survive the loss of your homeland and your family. So how did you first start writing, and how did it help you navigate life in exile? Bhuchung D. Sonam: I was taken out of Tibet when I was about 10 and a half or 11. I’m not very sure, but probably about 11. So then I went to Tibetan Children’s Village School here in Dharamsala, where I learned English and where I was also introduced to other Tibetan stories, like folk tales and namtar and the story of Milarepa and the songs of the Sixth Dalai Lama. So when I was in school, I was inspired to write in the style of particularly the Sixth Dalai Lama. So that’s how I started writing in Tibetan in exile, imitating the Sixth Dalai Lama’s songs. And then, of course, later when I went to Indian university, then I decided to write in English because I knew that if I went on reading in Tibetan, then my experience would remain limited only to Tibetan communities and the limited number of people who could read Tibetan. So I switched to English. And what writing does—by the way, I have never studied literature. I studied economics undergrad and postgrad. So I really know nothing about literature as people would normally know. I love reading, I read, but I think what writing does to me is I think it seals the pain. You know, I grew up as a refugee since I was very young. Throughout my life I lived in boarding schools here in the school and also in college, so for the last forty years, I’ve been living in one rented room after another. So that’s forty years of being dislocated from my parents and family. And then on top of that, if you add on the collective Tibetan suffering, then the pain becomes too much. I think writing kind of eases this frustration and loneliness and hope, and it also helps me to reroot myself and stay grounded to some extent. Because sometimes when I sit down and think about everything that goes inside Tibet and also outside Tibet, sometimes you get really depressed, desperate, and frustrated. You know, we are such a small community, and we don’t really have the luxury of being depressed and losing ourselves. So the other possibility is to try to use our frustration and anger and loss to create works of art, at least in my case, increasingly poetry and short stories and essays from my suffering so it eases my pain, and also in the process, it helps to tell my story to a larger audience. So that’s how I at least look at writing. Because first and foremost, you know, if I write a poem, for example, it feels so good. It takes so much of that inbuilt frustration and angst, and that I think is really good because it makes me much lighter and more sane and more grounded, so to speak. James Shaheen: Mmhmm. So you write in English now, and you learned English as a young refugee, and you said of one of your teachers, the way they put it was you have to eat the language, you have to sleep with the language, you have to shit with the language. So what does it look like to eat, sleep, and shit with the language when learning it? And how has this influenced your approach to writing and translation? Bhuchung D. Sonam: You know, I learned English from Tibetan teachers who probably learned it from another Tibetan teacher who probably learned from an Indian. So I never really knew how authentic the language I was learning when I was in school. And so in school we had great difficulty speaking in English, because we went to a primary Tibetan school where everybody is Tibetan, everybody spoke Tibetan. So then all of a sudden trying to speak English in English class was so hard. And that’s why one of the teachers said that, OK, if you really want to get into this language which is not yours, then you really tune yourself to think and sleep and dream and eat in this language. I might have been about 15 or 16, a very impressionable age at the time. So for a time being, I tried to do that, of course, but I think my proficiency in English by and large came from reading, because I read a lot and I still read a lot. So I think no matter how good a teacher is, he can impart only so much, and the rest you have to do by yourself, to get into the nuances of the entire expression. And then now, of course, it’s also contradictory, a lot of contradictions, because I am a Tibetan, but my identity as a writer or poet or whatever comes primarily because I write so much more in English than in Tibetan, but the central focus of our effort is to preserve our language and culture. But because of the circumstances, we are forced to articulate ourselves in this language which is not ours. So sometimes it’s a lot of contradiction because people do ask, “Do you write in Tibetan?” I say, “Of course I do.” But of course, I write far more in English. James Shaheen: Right. Yeah, I was wondering about that. I mean, you immerse yourself in another cultural framework, another language, and you’re living in exile, and you talked about the pain of exile. Did you feel you were pulling further from your heritage when you immersed yourself in that way? Or was it more like knowing both and using literature could serve as a bridge between multiple cultures, or can you say more about literature as a bridge? Bhuchung D. Sonam: You know, my writing in English was a choice that I made intentionally, as I said earlier, when I went to Indian university, so I knew what I was getting into. If I am to tell my story to a larger audience, then as a community living now at this time and age, that language has to be English. We don’t have any other choice. Then, for the act of translation, we look at Tibetan history and the fact that the Tibetan language is one of the richest corpus of Buddhist literature is because from about the 7th century till 1959, before we lost independence, for all of these nearly 1300 years, Tibetan scholars and translators were engaged in an act of translating from Sanskrit and Pali and other languages into Tibetan. So that’s how Buddhism played and continues to play a central role in Tibetan civilization, and also that’s how the entire Buddhist philosophical traditions emerged through the act of translation. And that in many ways continues to this day because now we have increasingly a great number of translators doing translations from Buddhism to other languages, by and large, into English. And for me, trying to create a bridge through my act of translation is a bridge between the exiled Tibetans and the writers living inside or by Tibet. You know, we have a lot of writers, poets, filmmakers, and musicians producing a lot of works, including a huge number of poems talking about many things including oppression and their desire for freedom. But within the exile community, we have had a lot of transition, a huge transition, with a number of Tibetans leaving the Indian subcontinent to Australia, Europe, Canada, and the US. So we have increasingly a new generation of Tibetans growing up in these places, in these countries, who may not speak Tibetan, who may not even read Tibetan, but because they are Tibetan, it is by and large the responsibility of people like us who at least are endowed with the two languages to make sure that we create bridge between Tibetans living outside of Tibetan, particularly in the West, and artists and musicians and writers and poets living in Tibet. So that act of translation is another bridge. Of course. Then we also have the larger international community to whom we have to make the rich corpus of Tibetan literature available for researchers and scholars and lovers of literature. So I think these are the to-and-fro interactions that continue to this day. James Shaheen: So you said in an interview with the New York Times, and I’m quoting here, “Until we find a political solution, we have to hold and build this idea of Tibet, whether you call it a home or an idea, and art does that.” So how does art help to hold and build the idea of Tibet? Bhuchung D. Sonam: You know, religion has prescribed things. There are very clear definitions: If you do this, then you are a Buddhist, or if you do this, then you are a Christian, or if you do this, or if you don’t do that, then you go either up or down, or things like that. Or politics, you know, if you define socialism or democracy, you have really set definitions. But with art, the beauty of art is that it’s infinite. Anybody at any point of time can define aspects of art in any way you want. Because of that, now, whether it’s contemporary Tibetan films or writing or stories or paintings, these give the new generation of Tibetans ideas about Tibet, particularly contemporary Tibetan expression through which they can engage in dialogues even without being in the same place. We are less than 200,000 Tibetan refugees, and we are scattered over more than thirty different countries around the world. So we are scattered all over. So the possibility for us to be together is very, very limited. Except for maybe the big religious festivals, not a large number of Tibetans gather together. But our aspiration for a future Tibet or an idea of a future democratic secular Tibet must go on. So if we are to create this community of people who have some invisible connection, as far as how I look at it, I think art does that, and this is because the music that is produced from Tibet, we can hear living here in India, or for anybody living in US or Canada or Australia or anywhere, it can be heard. It’s the same with books as well. Despite the fact that we may never have the artist coming from Tibet, all the books that we write or produce from here in India, they’re read by young Tibetans everywhere. So I think this creates a kind of a community where we may not be together in one place, but still we are connected. I don’t know any other channel other than art forms that can do that and play that role. James Shaheen: Well, related to that, you’ve also said that writing is a form of resistance and act to not be forgotten. How so? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Well, yeah, for any community or group of people fighting for their freedom, narrative is really important. It is said that he who tells his story better has a better chance of survival. And so it is the case with Tibet. You know, we are such a small community, although we have a really rich and long history, but right now, we are facing a humongous country with huge resources, both military and economic. And just look at the number of people, you know, 7 million Tibetans against probably 1 billion Chinese. So that’s how humongous the proportion is. And also the amount of resources that China puts in propaganda and revision and rewriting history, even renaming Tibet for that matter. They no longer call Tibet Tibet—they call it Xizang. So if the challenge is that big, then the least thing that we can do is ensure that we tell our stories in a way that we experience, in a way that we feel. I think that narratives based on lived experience are really important because ultimately the audience is smart enough to distinguish between a narrative that is based on lived experience versus propaganda that is churned to fool people. So in that sense, the act of writing is an act of resistance. Not just the act of writing but the act of creating a film, or the act of painting, the act of creating a piece of theater for that matter. So I think that is what art does in terms of resistance. James Shaheen: So would you be willing to read one of your poems that gets at the theme of exile? It’s called “Banishment.” Bhuchung D. Sonam: Sure, yeah. I wrote this poem many years ago, so I will read it. “Banishment” Away from home I live in my thirty-sixth rented room With a trapped bee and a three-legged spider Spider crawls on the wall and I on the floor Bee bangs at the window and I on the table Often we stare at each other Sharing our pool of loneliness They paint the wall with droppings and webs I give them isolated words net, maze, tangle wings, buzz, flutter Away from home My minutes are hours Spider travels from the window to the ceiling Bee flies from the window to the bin I stare out of the window Neither speaks each other’s tongue I wish You would go deaf Before my silence James Shaheen: Thank you so much, Bhuchung. So can you tell us a bit about that poem? Bhuchung D. Sonam: It’s a very typical exile poem. I wrote this many, many, many years ago in a rented room, actually. You know, it’s a very small room with enough space to fit two rooms and a small bookshelf on the side. In Dharamsala we have long, rainy seasons, so one side of the wall would get really wet with the water dripping, and we would have spiders and lizards and sometimes even scorpions crawling under the bed. So it was a very interesting place at that time. And we had a really tiny bathroom and the kitchen outside with a small veranda. So I lived in that place for about three years. So that’s the place where I wrote this poem many years ago. James Shaheen: So in addition to your own writing, you also cofounded TibetWrites, which is a press and online platform for Tibetan writing. Can you tell us about TibetWrites? What was your aim in founding the press? Bhuchung D. Sonam: TibetWrites we started way back around 2003. Actually, there were two other friends along with me, Tenzin Tsundue, who is a writer and Tibetan activist, and our other friend, Tenzin Namgyal, who has now settled in France, but at the time he was the editor of the Tibetan Bulletin, which was the English news bulletin published by the exiled Tibetan government. So the three of us got together, and I was working on an anthology of Tibetan poetry at the time, Muses in Exile. And then we came upon talking about where can one find Tibetan literature? We knew quite a number of young Tibetans were writing, and we knew of our older generation who also wrote in English. But at the time we didn’t have any one place where we could guide people to say, “OK, if you go to this website, you can find Tibetan writers.” So that was the original idea. And we started TibetWrites for Tibetan writers writing in English and also Tibetan writers writing in Tibetan that we translated into English. It was a platform created for Tibetan writers, and one of the reasons was also because we knew that a fairly good amount of writers were writing, but the possibility of a mainstream publisher giving space for young Tibetan poets was very, very rare. So we wanted to make sure that at least we had one website where people could find Tibetan writing. But then eventually we started getting quite a number of submissions. Some people would send ten or fifteen poems for that matter, and you can’t just dump fifteen poems on a website. Then we started with the idea of publishing books, and we eventually registered ourselves with the International Standard Book Number based in Delhi. We got the number, and that’s how we started. You know, of course, the larger idea that we had was to make sure that the lived experience has space. As you know very well, after we came into exile, Buddhism became hugely popular. Of course, it has played a crucial role in a central role in Tibetan civilization. But also, after we came into exile, it became a huge thing. And by and large, we have taken good care of Buddhist philosophy and traditions as well, because we have huge humongous monastery institutions who are well established. But what we have noticed at the point was we didn’t have any special focus on literature that was produced by Tibetans who are not a geshe or a rinpoche or a tulku or a well-known monk. And so there was this kind of dynamic where we thought that which is not given much focus within the community and also from outside, we must make sure that that has its own space. So that’s how we started with TibetWrites. James Shaheen: Right. You say that dating back to the seventh century, most Tibetan literature was Buddhist literature, and there hadn’t been a lot of secular writing. So can you tell us about the development of Tibetan secular writing? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Well, secular is a complicated thing, you know? Because if you look at Tibetan writing even now, it is one way or another going to be influenced by Buddhism. Even in my own writing I’m influenced. You know, many years ago I did a reading at Delhi University, and I read a poem that had the word “graveyard.” One of the teachers asked me, “You know, Tibetans don’t have graveyards. We have sky burial and cremation.” So then all of a sudden it struck me how indeed this graveyard came into being, and I looked at how I was influenced here. I was taught a lot of old English writers, like Shakespeare and Wordsworth and Blake, and we were also taught American poems and literature, and then I read a lot of Western literature. So that’s how, without my knowing, that graveyard seeped into my writing. It’s the same with Buddhism as well. So to say that there’s purely secular literature, I can’t really say, but I think one of the landmark changes, of course, was 1959. Until then, most educated Tibetans were either monks or nuns, primarily monks. So because you are a monk, your outlook toward the world is through the prism of Buddhism, so your articulation would be likewise. Then came the Chinese with their socialist realism and communism and the need to propagate socialism and communist ideas within the Tibetan community. So they brought a lot of socialist jargon and words, so that was a change. And then when we came into exile, we were also hugely exposed, as I said, to Western literature. So I think there were these landmarks, so I can’t really say when secular Tibetan literature evolved or its status here. But what we’ve been trying to do is to focus on writing that is written by ordinary Tibetans, Tibetans who actually lived through their life and then talk about or write based on that validation. James Shaheen: Right, although there’s been considerable investment in translating Buddhist texts into English and other languages, you say that stories of ordinary Tibetan experience have been largely neglected by Western scholars and by the Tibetan exile government, and this Buddhist focus has led to a simplistic or reductive image of Tibet that obscures the murkier and more complex parts of its history. So can you say more about this? What gets left out or flattened when we put aside these more ordinary experiences of Tibetans? Bhuchung D. Sonam: One of the things that at least I find very difficult to find in the existing Tibetan Buddhist literature and associated literary production, such as namtar biographies of lamas, is we don’t find any daily experience-based things. It’s always about enlightenment, meditation, and compassion, and the need to achieve enlightenment for the benefit of others. So it’s almost this really huge focus on the philosophy and the practice, not so much on the ordinary things that would happen. Even in a great lama’s life, there would be many ordinary things that would’ve happened, but we can’t find them. That’s why I always tell young Tibetans, you know, we say that Songsten Gampo is one of the greatest Tibetan kings. We know a lot about how he introduced Buddhism and how he promoted Buddhism and a lot of these things, but we don’t really know what his favorite foods were, or what kind of clothes he wore. What kind of knives or swords did he have? What kind of horses did he ride? We have no information whatsoever, so it makes history really far from our reality. Two of the characters from Tibetan history that people love so much or that people are so connected with are Milarepa and the Sixth Dalai Lama, and I think this is because Milarepa lived as an ordinary person, and all his writing has to do with his lived experience. Even when he was teaching Buddhism, if he was teaching to a nomad, he would use yaks and yakherds and saddles and rope and tans and all of that. So his writing came very from his lived experience, and things that he witnessed. And of course, the Sixth Dalai Lama’s songs are very secular, very ordinary, very simple, again, based on lived experience. So I think, how wonderful, if we had a whole lot of other historical great saints whose biographies or whose writings are like that, full of life, full of experiences based on their lived experience. So I think that’s what is missing as far as I know. I love to read namtars, for example. We have great scholars, you know, hundreds of great scholars. But reading the namtar, after a while, it’s almost the same thing. You know, there’s always a lot about promotion and his deeds and mystical attainments, almost bordering legend and mysticism. So from my reading of this literature, that is what I think is missing: the ordinary small things that make people emotionally connected to the story and the person and the history. Also, when we talk about literature, I think any good literature should give you context to a time and society of that time, and that is what we cannot find in many of the namtars, for that matter. James Shaheen: You know, Bhuchung, earlier you said that Buddhism or Buddhist culture naturally finds its way into the writings of Tibetans, both in Tibet and in exile, and it reminded me of something that the writer Tenzin Dickie said. I know you’ve worked with her. She said that the Buddhist ideal has always been the elimination of desire, and fiction, of course, begins with desire. She says the two literature are diametrically opposed. What do you think about that statement? Bhuchung D. Sonam: It is interesting and very intriguing indeed. You know, the central Buddhist theme is indeed to do with anger, hatred, and jealousy, the negative emotions. But of course, if you’re an artist, if you are devoid of all of these basic human emotions, then what do I talk about? What do I write about? Where does my impetus come from if I don’t have frustration, for that matter, or love or affection? So I think the boundary is very hazy, you know? So how does, for that matter, a Buddhist master, such as Je Tsongkhapa, for example, how did he come to write everything that he wrote without some sort of basic human emotions, whether it’s anger or hatred or jealousy or whatever? But of course, the philosophy itself, the idea of interdependence of all things or to look at things, if possible, with great equanimity, I think these are really important in my own life. I try to conduct myself by and large based on the idea that everything is interdependent, that things that I do have impact not only on my own self but also on others, and that who I am now is dependent on many other things, including the Chinese occupation of my homeland, which resulted into my coming into exile and everything that happened to us. So I think the philosophy itself, that’s what I was trying to talk about, that the philosophy, the basic philosophical outlook, kind of seeps into who we are as people. Although we may not overtly chant mantra or offer butter lamps or go to monasteries that often, because it has fundamental influence in all aspects of our life, we are shaped in many ways by the philosophy, and as a result, even without so much thinking about it, it seeps into what we do and also how we write. James Shaheen: You know, Bhuchung, as you mentioned earlier, you write poetry in English and in Tibetan, and you said that you don’t translate your own work: If you write in English, it remains in English, and the same with Tibetan. Why is this, and how do you see the differences between your English writing and your Tibetan writing? Bhuchung D. Sonam: Yeah, I think poetry is such a powerful and spontaneous thing. You know, if something strikes you, it’s just there. You know, if that something comes to me in English, I write in English, and that initial, spontaneous, highly elated experience remains within that moment, right? So I write a poem in English, and that takes everything, the frustration and anger and everything, away. So that is a complete act by itself. Now, if I try to translate this piece of writing from English to Tibetan, then if I’m the translator, then my first thing that I look for will be that initial experience, you know, that spontaneous, elated experience, which either lifted my burden away or gave me a huge sigh of relief. In the act of translation, I don’t find that experience. It cannot transfer. So I feel very disappointed, so that’s one of the reasons I never translate. The other reason also is because I learned Tibetan as my mother tongue. So Tibetan came naturally to me. It’s very natural. Because I spoke Tibetan, it came very naturally. I grew up with that language, whereas I had to learn English when I came into exile in the Tibetan refugee school here in India. So now I had no choice. And along with not having choice also, the experiences of being dislocated from my family and the state of refugeeness and longing and loss, all of these came along with me as I was learning English. So that might have something to do with that because the things that I write in English are slightly more dark and sad and cloudy, almost like a sunset feeling, and things that I write in Tibetan are much lighter. It’s almost like morning and evening. So in that sense, it is almost useless for me to engage in the act of translation, although I knew some people did that, but it’s entirely up to them because they didn’t have that initial experience or spontaneous feeling of being punched by a piece of poem, so they can do it because they don’t have that judgment. I do. So, yeah, that’s why the things that I write in English remain in English and the things that I write in Tibetan remain in Tibetan. James Shaheen: Well, that makes sense. That answers that question. So, to close, Bhuchung, would you be willing to read a couple of poems? First, how about “Yonrupon’s Daughter”? Bhuchung D. Sonam: “Yonrupon’s Daughter,” that’s a long one, right? James Shaheen: Yes, not too long. Bhuchung D. Sonam: “Yonrupon’s Daughter” And then I saw Lhadon coming from afar A golden sceptre in her hand – thunder flashed, sky blackened fog entered my mind fear shook my heart tears stung my eyes For a moment I thought She was going to strike me into fragmentation My useless self splattered in ten directions I pinched myself I punched myself I kicked myself I was looking for a runaway exit The Great Wall of China stood behind me – I was locked, shocked There was nothing I could do In desperation I faced her She was still coming towards me Now holding a bouquet of white roses Seeing me she raised her hand And the roses disappeared Petals swirled in the sky Thorns rained down – thud thud thud heavy heavy heavy I gaped my mouth My heart pounded on a Chopping board The sun shone in the sky Light streamed into my head I wanted to jump, shout, cry, pounce Wozila! Wozila! illusion . . . delusion . . . hallucination . . . I banged my head on the wall Focused my eyes straight forward And saw Lhadon . . . Now dashing towards me Locks of hair waving in the wind Her boots pounding the dry earth Puffs of dust flying in air She was a wild yak in the Himalayas Blood raging in her veins like Yarlung River I stared into the sky and prayed Prayed to a million gods and goddesses I knew Chenrezig Khyenno! Jampel Yang Khyenno! Jetsun Dolma Khyenno! Palden Lhamo Khyenno! Gonpo Ludrup Khyenno! Arya Deva Khyenno! When I finished chanting the last name Of the last god thinking this Was my last day on this earth . . . Silence occupied the universe The world sank to a deep coma The sun stopped The wall behind faded There in front of me was Lhadon fisted hand stretched towards me I was speechless . . . I did not know what to say . . . Do I have to say something? Do I? Then . . . Then . . . She slowly opened her hands and in her palms were the broken fragments of the yellow stars She plucked from the wall of the People’s Great Hall My head reeled in excitement My heart struck my chest From somewhere deep inside I found my voice . . . Ah! Lhadon, I said This is what I’ve always wanted to see The broken fragments of those yellow stars That covered my mother’s snow Darkened my father’s sky Those yellow stars They blocked my grandfather’s rivers Pierced my grandmother’s tent Yellow stars fractured my dreams. I looked about And realized There were people around me All along there were voices Voices saying many different things Ah! Lhadon You are Songtsen Gampo’s niece You are Yonrupon’s daughter You are Thupten Ngodup’s sister I am Lang Darma’s grandson Dhondup Gyal’s cousin. You and I travel the same road. At the end of this road is the land We came from. James Shaheen: You know, thanks so much for reading that. I guess it is a long poem, and I certainly enjoyed it. The online version is abridged, so that was a real treat to hear the whole thing. Can you tell us something about that poem? Bhuchung D. Sonam: I wrote this many, many years ago. Lhadon is a friend of ours. She’s one of the foremost Tibetan activists. This was I think around 2008, when the Beijing Olympics was happening, and she was at the forefront of our activism. But I also didn’t want to focus entirely on the historical events of the time. I wanted to bring those elements and also take it to a slightly different direction, a different level. So that’s why I made it almost like a Ling Gesar story. There’s a lot of rhythm and cadence, almost like rushing. And that’s how resistance is. I also wanted to bring historical characters. As I was saying earlier, Buddhism in one way or another seeps into who we are and consequently into our writings as well. That’s why there’s Chenrezig Khyenno and Jampel Yang and Arya Deva and other things. Then, because it’s a very contemporary poem, I also wanted to bring contemporary characters, such as Yonrupon, who was a young Lithang resistance fighter who fought the Chinese in Lithang monastery. I think he was 26 or 25 at the time when he was killed. And Thubten Ngodup was arguably the first Tibetan to set himself on fire for Tibet’s struggle for freedom. And then of course, there’s the historical character Dhondup Gyal, who was one of the foremost Tibetan writers, who died at the age of 32 in the early 1980s. His writing revolutionized Tibetan writing, moving from a very traditional classical regimented writing to free verse. He and I would speak with a lot of emotion. So, yeah. James Shaheen: Thank you. I wonder if you could read a poem called “Dog Dead.” Bhuchung D. Sonam: Oh, yes. I think it’s somewhere in here. This poem is one of the shortest, I think. Many people read this poem and have their own interpretations, which is what I really like about it. It’s a short poem, but, yeah, where is it? Let me find it. “Dog Dead” There is no such thing as middle path. We all gravitate to our sides. If there is a path in the middle I would be the first to find it. I am neither here nor there . . . To her right To your left Far from their centre. There is a dog chewing a bone In the middle of the path. A truck comes Speeding James Shaheen: Thank you. You know, I have to ask, dogs seem to be recurring characters in your poetry. In one of your earliest poems, you compare yourself to a stray dog clinging to the dry worldly bone, and in another, a dog receives instructions from Gandhi. So could you tell us a bit about this fascination with dogs? Bhuchung D. Sonam: I mean, the relationship between human beings and dogs probably dates back, I don’t know, as long as there were human beings. When I was in Tibet, we had a pet dog called Jachung, and my name is Bhuchung, so we share the second part of our names. So then of course I was taken into exile, and at the refugee schools, we had a lot of stray dogs, but we never had the possibility of keeping a pet dog. And even now we don’t. So my fascination with dogs has to do with this early memory of having a dog in our house when I was in Tibet. And then, you know, because in India they are such an integral part of any society, you will not escape from dogs anywhere. I mean, anywhere you go. I think it is reported that India has something like 36 million stray dogs. So you can imagine, any place you go, you would come across dogs, and because they are such an integral part of my life here in India, I often think about what if I was a dog, or what if a dog could speak? What if a dog could do this? So that’s why in Songs from Dewächen, which is one of my poetry books, I had a dog, or a number of dogs, in each of the poems. There are something like thirty-five poems. Also, there are things that I do not want to say and things that are easier said through the mouth of a dog than from my perspective.So I wanted to have dog characters for many different reasons. You know, social satire, for that matter, it’s far more powerful if it comes out of a dog’s mouth than my mouth. Anyway, I like dogs. I think they’re fascinating animals. Every time I see a dog, I look at it and try to figure out what it might be thinking. James Shaheen: Yeah. We project so much onto dogs, but we will never really quite know what they’re thinking. Bhuchung D. Sonam: Yeah. That’s the gift that they can give us of imagining what it might be like if you were a dog. James Shaheen: Right. You know, I have one last question, and perhaps you’ve already touched on it. You talk about art creating and preserving this idea of Tibet, and I’m wondering how you see the relationship between that idea of Tibet and the actual Tibet. Are they divergent? Are they in dialogue? Do they help shape each other? How do you think of that? Bhuchung D. Sonam: I think for people who were born into Tibet who then were driven into exile, their idea of Tibet and their association with Tibet is very different from those who were born in exile, particularly the third and the fourth generation. For them, Tibet, by and large, becomes a mental image constructed from stories they have heard, or books they have read, or maybe a picture they’ve seen on social media or maybe a story that they heard from their parents or grandparents. So, for the younger generation of Tibetans, their idea of Tibet within their mind might be very far from what actual Tibet is. You know, I was born in Tibet, and the village that I was born in, the village that I knew at the time, I know is no more. But I still cling to that idea, because that is personally precious to me because that is the only place in Tibet where I lived and grew up. So depending upon where you are at this point of time, you build your connection with Tibet based on that. And here, as I said earlier, the act of telling stories and the act of writing and creating art plays an important role because for a young girl born in New York who may not speak Tibetan who may have no access to Tibetan culture and language and anything, but nevertheless, for her, she is Tibetan. So how can we give her things so that her idea of Tibet is rooted in something? A story, a song, a piece of art, anything? And I think that link is really important not only for the sanity of that individual, but also for the larger struggle to continue. Because anybody who does not have any connection with Tibet, his or her stake may also be less because he or she may not have any connection with the idea of Tibet. So I think it is really important for us to make sure that we continuously tell our stories and produce books and stories and films so that the subsequent generation of Tibetans can still have that idea and still have that connection to Tibet, whether it is an actual reflection of Tibet that exists physically or not. How wonderful that each of us have our own Tibet to cling on to. James Shaheen: Bhuchung D. Sonam, thanks so much for joining us. It’s been a great pleasure. For our listeners, be sure to check out Bhuchung’s writings at TibetWrites. Thanks again, Bhuchung. Bhuchung D. Sonam: Oh, thank you very much. Such a pleasure to talk to you. Thank you very much. James Shaheen: Thank you. James Shaheen: You’ve been listening to Tricycle Talks with Bhuchung D. Sonam. To read Bhuchung’s review of the Dalai Lama’s latest book, visit tricycle.org/magazine. Tricycle is a nonprofit educational organization dedicated to making Buddhist teachings and practices broadly available. We are pleased to offer our podcasts freely. If you would like to support the podcast, please consider subscribing to Tricycle or making a donation at tricycle.org/donate. We’d love to hear your thoughts about the podcast, so write us at feedback@tricycle.org to let us know what you think. If you enjoyed this episode, please consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts. To keep up with the show, you can follow Tricycle Talks wherever you listen to podcasts. Tricycle Talks is produced by Sarah Fleming and the Podglomerate. I’m James Shaheen, editor-in-chief of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Thanks for listening!

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.