‘Culturally specific venues allow safe spaces to become sacred spaces through the exploration of dharma and meditation practice,” Insight Meditation teacher Larry Yang wrote in his book Awakening Together. “They invite the universality of the teachings to be felt through the particulars of one’s own cultural experience—to see and directly experience how relevant these teachings are to each life.”

Until recently, the first and last time Spirit Rock Meditation Center organized a gathering for Asian Dharma practitioners was the Asian American & Pacific Islander Dharma Retreat and Conference in 2004. Led by Larry Yang, Buddhist teacher and activist Mushim (Patricia) Ikeda-Nash, and artist Michele Benzamin-Miki, this retreat offered teachers, leaders, and practitioners of Asian descent an unprecedented opportunity to meditate together and foster mutual support as Buddhists.

An Asian-specific retreat provides a sacred arena to explore what it means to be an Asian Buddhist in Western convert contexts. For these practitioners, the experience of being a minority is further complicated by the mostly white founding teachers and history of American convert Buddhism, which can render the dharma’s Asian lineage largely invisible.

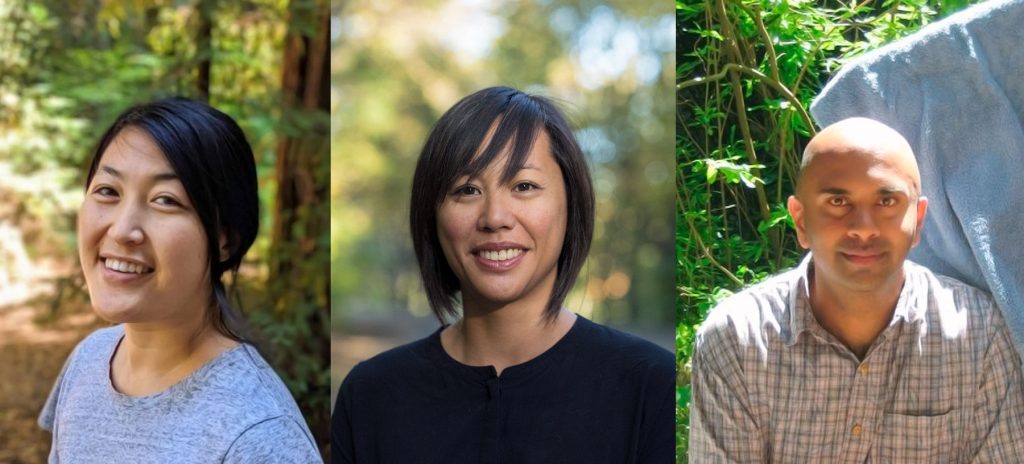

I recently attended Coming Together: A Retreat for Asians in the Diaspora, a weekend retreat held virtually and led by Dawn Mauricio, Gulwinder “Gullu” Singh, and Louije Kim, all of whom are second-generation immigrants and members of Spirit Rock’s Teacher Training Class of 2020.

A gathering that centers Asian voices allows practitioners to embrace the diversity of their experiences as belonging within the domain of Western convert Buddhism. The cultural specificity enables community practice that does not require participants to position themselves in dialogue with white supremacy or within broader conversations about race.

The last few decades have seen impressive efforts to foster more diversity and inclusivity within Western convert sanghas such as Spirit Rock, along with more offerings for practitioners of color in general and for African American practitioners specifically. In fact, the immediate inspiration for “Coming Together” was The Gathering II, a two-day non-residential retreat held at Spirit Rock in October 2019 for Buddhist teachers and practitioners of Black African descent.

Still, while there have been ongoing efforts to foster more inclusivity in Western convert sanghas, it was only over the weekend of May 9–10, 2020, that practitioners of Asian descent were offered their second opportunity in sixteen years to gather and practice dharma together.

Each of the teachers independently realized the need for an Asian-specific retreat, driven by their own experiences meditating and teaching dharma in predominantly white, Western convert spaces. Dawn, a Filipino Canadian, is a vipassana teacher and a board member for the meditation organization True North Insight. Since discovering vipassana in 2005 in Thailand, she has practiced in Burma, South Africa, Canada, and the United States. Gullu, an Indian American of Punjabi descent, came to Buddhism in 1993, when he started his career as a corporate real estate attorney. He is also a senior teacher at Insight LA. Louije, a Korean Canadian, is a community mental health therapist and Buddhist practitioner in the San Francisco Bay Area. Beginning their Buddhist journey in 2008, Louije is most drawn to meditation practice in the style of Burmese monk Sayadaw U Tejaniya.

“[In] my experience in Western convert spaces like Spirit Rock and the Insight Meditation Society, there’s just been a lot of dialogue about ‘how do we include [the] POC [people of color] community?’” Louije noted. Yet even in these conversations, “diversity is always in response to being in a white dominant space, or in a space that’s influenced by white supremacy.” The result is often an unfortunate flattening of the experiences of people of color as singular and undifferentiated.

Dawn’s efforts to include her experiences as an Asian practitioner when teaching has had a profound impact on Asian retreatants. “I often get notes from the few Asian practitioners in the hall just expressing huge gratitude for naming small things [from my experience] and for how that led them to feel seen in ways that, after years of practice, they didn’t really feel seen.” Gullu recalls similar occurrences of South Asians actively seeking him out while on retreat. “It’s just so telling!” he shared, “I don’t even have to do anything. Just my being there is some validation.”

In offering a retreat for the Asian community, Dawn, Gullu, and Louije aimed to create a space that recognized and validated the complexities of Asian experience. Over two days of practice via Zoom, the teachers offered guided meditations, relational practices, and dharma talks. Together, these offerings facilitated a safe space to examine the racialized tenderness evoked by vipassana meditation; to recognize the harm caused by stereotypes of the “model minority,” a term that drives a wedge between Asian Americans and other racialized groups, and perpetuates ideas about Asian Americans as monolithic; and to relax—mentally, physically, spiritually—amid those with similar embodied experiences and histories.

Four and a half of the retreat’s eleven hours consisted of relational practice: interpersonal exercises that cultivate mindfulness through dialogue, mindful listening, and pausing in present-moment awareness. For three-and-a-half hours, retreatants engaged in breakout sessions, where they recounted the stories of their names, examined experiences of belonging, and explored their identities as Asian meditators in Western convert spaces. An additional hour at the end of the retreat was reserved as an open chat for attendees to further connect.

The intention of these activities, Dawn explained, was to offer a “collective way of witnessing and seeing and holding each other” that isn’t always possible at North American vipassana retreats. In lieu of emphasizing individual, silent meditation practice and directed teachings that inadvertently privilege the Buddha’s first two jewels of Buddha and dharma, the teachers sought to cultivate and polish the third—sangha.

Retreatants found the focus on sangha to be especially meaningful. For attendee Yong Oh, these periods offered an enjoyable way “to connect with others through a practice lens around our shared experiences as well as our diverse histories and backgrounds,” he told Tricycle. “It was surprising how vulnerable and tender these sessions were, even through a virtual medium.” Yong’s sentiments were echoed by others who described the sessions as heartfelt, highly emotional encounters that supported a profound depth of Buddhist practice.

The ability for participants to connect in the dharma through a recognition of their shared backgrounds and experiences, while also celebrating their uniqueness, attests to the power of relational practices. Such practices cultivate an appreciation of what Zen Buddhist priest and author Zenju Earthlyn Manuel calls “multiplicity in oneness,”—how the relative and universal aspects of our identities come together in dharma practice. When communities of color are regarded as uniform subsets of the broader population, multiplicity—the ever-changing “kaleidoscopes” of their individual identities, as Louije puts it— are lost. And when spaces deemed sacred fail to recognize identities already rendered invisible in mainstream contexts, they inadvertently amplify feelings of oppression.

Approximately seventy attendees participated consistently, which surprised the teachers who were nervous about attendance for an online-only format. However, this adaptation forced by the global pandemic turned out to benefit individuals who were unable to travel or were new to meditation practice and Spirit Rock. The administration at Spirit Rock was highly enthusiastic about the retreat, and future Asian-specific gatherings are already in the works.

The participants’ overwhelmingly positive response to “Coming Together” demonstrates the hunger for culturally specific gatherings, especially at a time when acts of racism against Asians are rising and sheltering at home has left many of us feeling isolated. The need to continue such offerings was beautifully articulated by retreatant Taj Jegaraj, “The Asian affinity space provides…a sense of relief, allowing us to let our guards down and sink into a deeper sense of community we might not be able to otherwise (at this point) with other white or non-Asian folks around. A retreat experience like this allows us to feel a sense of belonging in our bodies that we can then bring with us into other spaces.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.