I was enmeshed in lay life when I began to practice Zen. I was married with children, finishing college, and starting a new job. I joined a small sangha and somehow managed to get to meditation and classes regularly. I loved my crowded family days, but I also loved the silence of practice. Although our little group was entirely lay, the two teachers, a married couple, were priests who had done strict monastic training. When I could, I traveled several hundred miles to a monastery for retreat. It was confusing.

Solitude is embedded in Buddhism; how many stories in the canon describe people leaving behind family and work to practice alone? Yet the Buddha preached to multitudes, his words falling on tens of thousands, dragons and divine beings jammed in beside a whole host of people below Vulture Peak. The famous Khaggavisana, the Rhinoceros Sutra (SN 1.3), was insistent: “One whose mind is enmeshed in sympathy for friends and companions neglects the true goal. Seeing this danger in intimacy, wander alone like a rhinoceros.”

Sangha is one of the three treasures of Buddhism, and even the Buddha’s most fervent monastic followers came together in community. How was I to understand this? My practice, everyone told me, took place in my ordinary daily life. But I watched several people in my sangha enter the monastery, spurred on by the ideal of ascetic withdrawal. I felt torn between worlds, living more like a bee in a hive than an aloof rhinoceros. The unexpected tension between community and solitude lodged in my heart and what I made of it had lasting impact. I had to investigate what being alone really meant.

I was anxious in relationships, always a bit guarded. The rare times when I was able to be alone were a relief, and sometimes zazen was just a way to avoid conversation. I couldn’t say the wrong thing when I was alone. I didn’t have to worry about rejection or whether I was charming enough. Alone, I relaxed in a way I never did with other people.

My teacher could see through my disguises. He knew the brittle control beneath my breezy ways. One day he gave me a verse to consider, an old saying with many variations: “When you are alone, behave as though you were with the emperor. When you are with the emperor, behave as though you were alone.” I wasn’t sure what this meant; I thought he was telling me to be braver. But I had grown tired of constantly managing how I appeared. I had also come to see that being alone didn’t mean I was keeping the precepts. I harbored grudges and nurtured pride. I gossiped silently. I still felt resentment and envy.

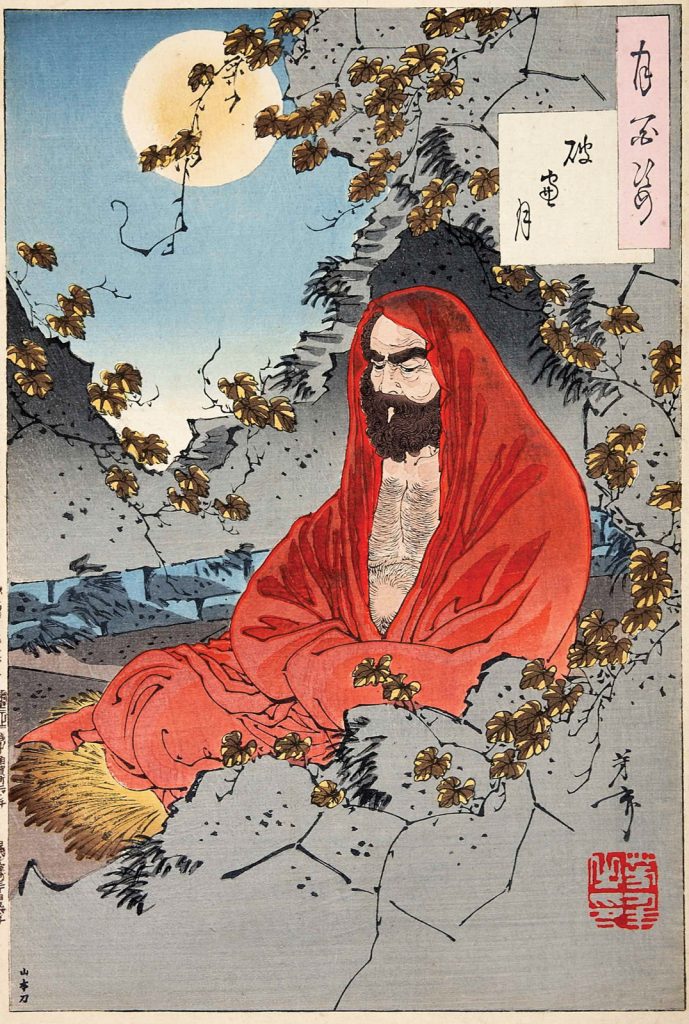

Then I read the story of Bodhidharma’s meeting with Emperor Wu, recounted in Case 1 in the Blue Cliff Record (Jpn,. Hekigan-roku). The story takes place during the Liang dynasty of China, in a fierce and dangerous world. When Emperor Wu hears about the barbarian monk named Bodhidharma, he commands his presence in court. The Emperor tells Bodhidharma about all the temples he has had built, the sutras he has distributed, how much money he has spent to spread Buddhism.

“How much merit does this bring me?” the Emperor asks.

Bodhidharma answers, “No merit.”

The Emperor isn’t happy with this answer, and they debate a little while. Then the Emperor demands to know what is the highest Truth, if not this?

Bodhidharma says, “Empty, without holiness.”

This shocks the Emperor. No holiness? Then what good is his effort, his wealth, his throne? “Who speaks to the Emperor like this?” No one had ever done so before now.

Bodhidharma answers, “I don’t know.”

I was taken with this koan exchange, the story of the fearless wanderer, tracking dust into court and leaving with a shrug. I didn’t understand the underlying dharma messages then; all I took from the story at first was the image of a natural person, unchanged by the presence of others. That seemed a great gift, one far out of my reach. I was weary of protecting a fragile self who feared Emperors at every turn. I was especially tired of hiding the fact that I had a fragile self to protect at all. I was tired of being a good Zen student who understood what this was all about. I had, finally, to admit that no one was going to fix me but me. In a crucial way, I was always alone. No one did my practice but me. No one sat for me. Only I could make my vows; only I knew what was in my heart when I did. Alone could be a relief, alone could be painful, but alone was where I had to find my way—whether people were present or not.

Alone could be a relief, alone could be painful, but alone was where I had to find my way.

I had to begin with my loneliness, my terrible separation from others. I slowly faced my narrow human isolation. I had to ask myself why other people seemed so necessary and at the same time so dangerous. Who were these Emperors? Who threatened me? To whom did I kowtow in defense? What would it be like to just be as I was? I did this in the silence of meditation and retreat, when loneliness sometimes sat on me with a crushing weight. I did it by meeting my teacher face-to-face and struggling to show up without a mask. I labored beside others in the sangha, as we drove each other to irritation and despair, until we polished each other like rocks in a grinder. Loneliness is the feeling that one is not complete alone. What if it turns out nothing is missing at all? What if nothing changes when another person is near?

How did Bodhidharma do it? Without hurrying. With persistence. He could behave as though he was alone when he was with the Emperor because he had long before learned how to act as though he were with an Emperor when he was alone. Solitude isn’t enough. We have to learn in that solitude to sit up straight and be vigilant on our own. Bodhidharma spent many years facing the wall that was his own self. Then he could answer the Emperor as he had learned to answer himself.

Every day we can practice this particular, sacred aloneness. It takes time. The Rhinoceros Sutra is not teaching us that we must retreat from the world. The sutra is teaching us to retreat inside ourselves. To face ourselves, undistracted by others. Alone we must encounter the depth of our attachments and fears, and see the self—the empty self—as it is.

When Bodhidharma says to the Emperor, “No merit,” he is not saying that merit doesn’t exist. He means that it exists only outside the realm of ego, outside the Emperor’s concern about merit. The monarch’s self-consciousness about his actions negates the merit. There is nothing personal to be gained—nothing for the Emperor himself. No self to be affirmed. In fact, Bodhidharma’s answer, “Nothing holy,” punctures the fantasy of the constructed self.

All those years of creating a veneer, a separate self to please each person I met, a mask to cover the actual confusion inside, the constantly shifting sand of no-self: mere vapor.

Dogen wrote, “The Tathagata [Buddha] has no outside in the same way as fences and walls have no outside. Just as the triple world has no outside, living beings have no outside.” In unpredictable shining moments, we drop our separation. Our small aloneness disappears, the boundaries expand and reform, embracing everything that had seemed to be outside. When we snap back to this particular body in which we find ourselves, we can bring back with us a memory of being unbounded. It is an outlaw experience to need nothing, to fear nothing. In those moments we know the Emperor within: a benign guide with far-seeing and forgiving eyes. We know in our hearts that here is the true authority, the unavoidable authority, the one to whom we will always have to answer.

This is freedom, and there is no need to point at it. What if we can be intimate with the entire world? This can happen in small, quiet ways. It isn’t dramatic. To simply be alone is to be whole within one’s self, and this radical solitude exists whether or not we are with others. The pointer at the beginning of Bodhidharma’s koan says this: “He is free to arise in the east and sink in the west, to go against or to go with, in any and all directions, free to give or to take away.” From such a stance, we never need fear the Emperor or retreat from others. There, no Emperors exist at all.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.