Keep practicing. Don’t be discouraged. The reward of meditation practice awaits us if we keep up the practice. People are searching for happiness in the world, but it’s never full or satiated, this worldly happiness. It’s always lacking and imperfect. It’s like a drug. You take it, inject it, or inhale it, and you feel good momentarily. Then suffering arises again. Then you get hungry. There is no real happiness in the world.

When we come to practice meditation, we aren’t aiming for happiness. We are aiming to learn suffering. Make sure you have the right objective. If you’re practicing for happiness, you won’t find it. Happiness is an illusion. When suffering is reduced, you feel happy. When suffering increases, then you feel suffering. But if we have the proper aim in practicing meditation, we will be practicing to learn suffering. When we learn suffering, then our mind lets go of suffering. The mind transcends suffering. When the mind has transcended suffering, we don’t have to talk about happiness. That’s just a freebie. Simply not having suffering—that’s happiness.

But if you aim for happiness, you will have even more wanting. When there is no happiness, you want it, and when there is happiness, you want it to last forever. But in reality, there will soon be suffering. You can’t have happiness all the time. When the mind has desire, wanting arises. The mind struggles, and suffering arises again. The worldly way is to feed desire all the time. We want, and we try to constantly feed our wants. We hope that by feeding our wants we will be happy, but the happiness only arises momentarily. Then you want something else. There is no fulfilment or satisfaction with worldly happiness.

If we know suffering, we know that the task in relation to suffering is not to get rid of it. The Buddha did not teach us to get rid of suffering. He taught us to know suffering. Once we know suffering as it is, seeing the truth as it really is, we see that this body is itself suffering and the mind is itself suffering. When you see suffering clearly, the mind will unwind its attachment.

To see suffering is to see things as they are. The Buddha said that, through seeing the truth, seeing the body and mind, seeing physicality and mentality as they really are, there will arise disenchantment. With disenchantment, clinging is released; with the release of clinging, there is liberation. When there is liberation, there is the knowledge that one is liberated. Birth—the action of the mind clinging to eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind—is ended. The holy life—that is, the practice of the dhamma—has been completed. There is no further task to be done for purity and liberation.

Worldly work is never completed. For instance, today you cook a meal to eat; tomorrow you have to find something to eat again. Today you have a shower; tomorrow you have to shower again. You buy a house, then you have to repair it. There’s no end to it. But knowing suffering, knowing the body and the mind as they really are, leads to the end of the tasks of our mind.

The science of the Buddha is an amazing science. Others searched for ways to resolve suffering. Some of them could see that if you had wanting, you would have suffering. They were clever. They searched for ways to destroy wanting by tormenting it: If you want to eat, don’t eat; if you want to lie down, don’t lie down. But they were only half clever. They knew that wanting was the cause of suffering, but they did not know how to deal with things in order to get rid of wanting. They used the method of denying it.

Another group sought to get rid of suffering by satisfying desires: If you want to eat, eat. If you want to lie down, lie down. If you want to travel around, then travel around. Whatever you desire, satisfy it. Whenever you satisfy a desire, the desire goes away and you feel comfortable. But in no long time suffering arises again. There is no end to it.

The Buddha taught us to know suffering. As soon as you know suffering clearly as it is, then samudaya, the cause of suffering, will be automatically abandoned. As soon as the cause is given up, cessation (nirodha)—that is, nibbana—will automatically appear. You don’t have to go searching for nibbana anywhere else. Nibbana isn’t in the temples; it isn’t at Wat Suan Santidham; it’s not with me; it isn’t with the Buddha. Nibbana lies in front of us, but wanting (tanha) obscures it. Our eye, our dhamma eye, is closed off by wanting. So we don’t see nibbana, even though it is right in front of us.

Our eye, our dhamma eye, is closed off by wanting. So we don’t see nibbana, even though it is right in front of us.

You must learn suffering, learn the truth of the body, learn the truth of the mind, and keep on with it. If you have a lot of good accumulated perfections, you could attain arahantship in only one day, seeing the truth of the body and mind in full. If your merit is a little less than that, it might be three days or seven days, seven months or seven years. If your merit is less than that, it might be seven lifetimes. Keep on practicing.

The Buddha taught that we attain purity through wisdom. This wisdom is not worldly cleverness. True wisdom is knowing the truth of suffering (dukkha). When you clearly know suffering, you give up the cause (samudaya), and you realize and attain cessation (nirodha), which is nibbana. And at that moment when you touch nibbana, the noble path (magga) arises.

Suffering—know it; the cause—relinquish it; cessation, nibbana—realize it; the path—develop it. All these four tasks are performed at once. We complete them all at once, in the one moment. When we see suffering, we relinquish the cause; when we relinquish the cause, we realize cessation; when we realize cessation, then we have developed the path. These four tasks are completed at the one place in the one moment. At the one place: That is at this very mind, in only one mind moment.

Our task is to know suffering. Get it done, know suffering: Know the body as it is, know the mind as it is. This is the science of the Buddha. What do you get from it? First, the end of desire. This is called viraga. The end of suffering, liberation from suffering: This is called vimutti. There’s the end of mental struggle, which is called visankhara. When you reach nibbana, it’s santi, peace. These are all names for nibbana. We can experience nibbana, see nibbana, when we clearly see suffering. There is no other option. You must know suffering; you must know the body and the mind. Know them as they are.

How can we know the body and the mind as they are? The important tools are right mindfulness and right concentration. Mindfulness is not just the worldly kind of mindfulness. All skillful mental states contain mindfulness, but the mindfulness that enables us to attain the path and fruit is the four foundations of mindfulness: kayanupassana, or mindfulness of the body; vedananupassana, or mindfulness of the feelings, which is mindfulness of mentality; cittanupassana, or mindfulness of the mind (citta), which is mindfulness of mental volitional activities (sankhara); and dhammanupassana, or mindfulness of dhammas, which includes both physicality and mentality, both skillful (kusala) conditions and unskillful (akusala) conditions, and both causal and resultant conditions.

Try to learn your own body and mind. They have many, many forms. You don’t have to learn them all. Just do what you can do. For instance, if you are watching and being mindful of the body with out-breaths and in-breaths, you can use this breathing body to practice meditation. We observe the changes within the body through the breathing. The body that breathes out is one thing; the body that breathes in is another. The body that breathes out is impermanent; the body that breathes in is impermanent. The body that breathes out is merely a physical element; it is not our self. The body that breathes in is merely a physical element; it is not our self.

If you don’t like watching the breath, you could observe the bodily positions: standing, walking, sitting, and reclining. This is another kind of kayanupassana. The body standing is impermanent. The body that walks, sits, and reclines is impermanent. The body that stands, walks, sits, and reclines is merely a material object. This material object stands, walks, sits, and reclines. It is not our self that stands, walks, sits, and reclines. The body that stands is impermanent; the body that walks is impermanent; the body that sits is impermanent; the body that reclines is impermanent. Observe like this, and you will see that all physicality is impermanent.

So we know the body standing, walking, sitting, and reclining, the body breathing out and breathing in, full of impermanence, full of suffering, being oppressed, full of not-self, just a material object. It is a lump of elements. It is not ours; it belongs to the world. When you see this, you will be done with clinging to the body.

If you see the truth of physicality and mentality, you don’t cling. When you don’t cling, you don’t want. The mind does not delight in or despise happiness and suffering. It stops struggling. There is no wanting, no mental hunger. The mind is free of defilements and desire. It experiences a unique kind of happiness. When you want happiness, you struggle almost to death and don’t obtain it. You get it only for an instant, then it is lost. When you no longer desire happiness, when you just observe suffering, [seeing that] the body is suffering, the mind is suffering, when you let go of the body and mind, you obtain an incomparable kind of happiness. That’s the happiness of nibbana. It is a happiness that will cause tears to flow. “Oh, there is such a happiness like this?” It is a really powerful kind of happiness.

When wanting and clinging are gone, the struggle is gone, and you are liberated from suffering. When you are liberated from suffering, you have an incomparable kind of happiness.

Observe suffering; look at the body and the mind. This is the reason that we must watch our body and our mind. If you know the body and mind as they really are, you see the three characteristics of body and mind. When you see the truth of them, you become disillusioned with them and release your clinging. When wanting and clinging are gone, the struggle is gone, and you are liberated from suffering. When you are liberated from suffering, you have an incomparable kind of happiness. It is a happiness that doesn’t change in response to sights, sounds, smells, tastes, bodily feelings, and thoughts. It is a happiness that is independent of sights, sounds, smells, tastes, bodily feelings, and thoughts. It is independent of things that are uncertain. Sights are uncertain; sounds, smells, tastes, bodily feelings, and thoughts are uncertain. As long as you are dependent on things that are uncertain, then your happiness is uncertain. When you don’t rely on things that are uncertain, when you don’t rely on anything in the world, then you attain the true, perfect happiness.

So keep practicing. Today it might be difficult. In the future it will be easy. Just keep watching the body and the mind. Today there are many defilements. In the future there will be fewer. Today there is a lot of suffering, and it lasts a long time. In the future there will be little suffering, and for a shorter amount of time, until eventually suffering comes to an end. Whoever does it will attain it. But you have to do it properly. Don’t use the methods that the Buddha didn’t teach, such as the method of feeding desires. This doesn’t work. The method of denying desires, that doesn’t work either. The method of knowing suffering until you automatically relinquish desire: That’s the method that works.

♦

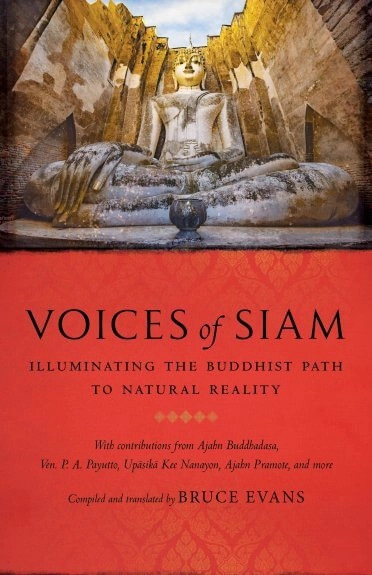

Adapted from Voices of Siam © 2025 compiled and translated by Bruce Evans. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. www.shambhala.com

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.