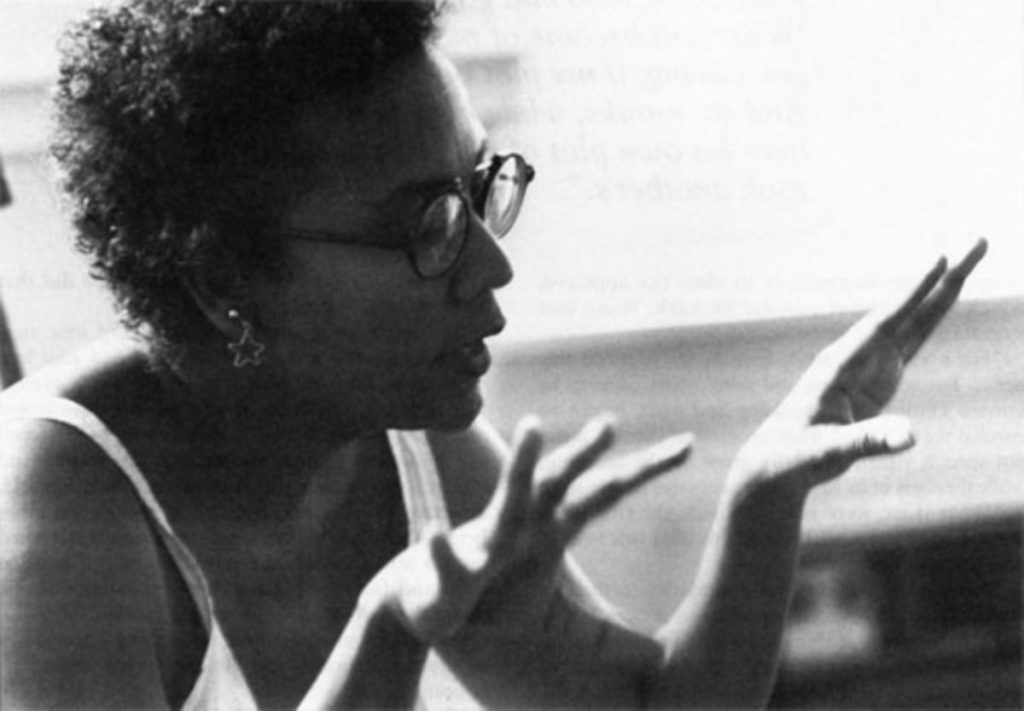

bell hooks is a seeker, a feminist, a social critic, and a prolific writer. Her books include“Ain’t I a Woman?”: Black Women and Feminism; Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black; Breaking Bread: Insurgent Black Intellectual Life (with Cornel West); and, most recently Black Looks all from Southend Press.

She was born Gloria Watkins forty years ago in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, and was educated at Stanford and Yale. Currently she teaches English and Women’s Studies at Oberlin College in Ohio. This interview was conducted for Tricycle by editor Helen Tworkov.

What was your first exposure to Buddhism? When I was eighteen I was an undergraduate at Stanford and a poet and I met Gary Snyder. I already knew that he was involved with Zen from his work, and he invited me to the Ring of Bones Zendo for a May Day celebration. There were two or three American Buddhist nuns there and they made a tremendous impression. Since that time I’ve been engaged in the contemplative traditions of Buddhism in one way or another.

And that excludes Nichiren Shoshu? Which is the only Buddhist organization in America with a substantial black membership? Yes, Tina Turner Buddhism. Get-what-you-want Buddhism—that is the image of Buddhism most familiar to masses of black people. The kind of Buddhism that engages me most is about how you’re going to live simply, not about how you’re going to get all sorts of things.

How do you understand the absence of black membership in contemplative Buddhist traditions? Many teachers speak of needing to have something in the first place before you can give it up. This has communicated that the teachings were for the materially privileged and those preoccupied with their own comforts. When other black people come to my house they say, “Giving up what comforts?” For black people, the literature of Buddhism has been exclusive. It allowed a lot of people to say, “That has nothing to do with me.” Many people see the contemplative traditions—specifically those from Asia—as being for privileged white people.

We find references and quotes from Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh throughout your work. Is part of your attraction to him his integration of contemplation and political activism? Yes. Nhat Hanh’s Buddhism isn’t framed from a location of privilege, but from a location of deep anguish—the anguish of a people being destroyed in a genocidal war.

In addition to Thich Nhat Hanh, the Buddhist references in your work extend to those books that fall into the category you defined as exclusive. How did you get past that? If I were really asked to define myself, I wouldn’t start with race; I wouldn’t start with blackness; I wouldn’t start with gender; I wouldn’t start with feminism. I would start with stripping down to what fundamentally informs my life, which is that I’m a seeker on the path. I think of feminism, and I think of anti-racist struggles as part of it. But where I stand spiritually is, steadfastly, on a path about love.

Does it have a name? If love is really the active practice—Buddhist, Christian, or Islamic mysticism—it requires the notion of being a lover, of being in love with the universe. That’s what Joanna Macy talks about in World as Lover, World as Self (Parallax, 1991). Thomas Merton also speaks of love for God in these terms. To commit to love is fundamentally to commit to a life beyond dualism. That’s why love is so sacred in a culture of domination, because it simply begins to erode your dualisms: dualisms of black and white, male and female, right and wrong.

“To commit to love is fundamentally to commit to a life beyond dualism. That’s why love is so sacred in a culture of domination, because it simply begins to erode your dualisms.”

Considering your critiques of the sexist, racist patriarchy, this path of love is pretty challenging. That’s why I enjoyed Stephen Butterfield’s article (in Tricycle Vol. I, Number 4) dealing with sexual ethics and Buddhist practice—precisely because he said, Let’s leave this discourse of right and wrong, and let’s talk about a discourse of practice. Something may in fact work for one person, and may be fundamentally wrong for another, and that’s complex. If I’m a teacher and you enter this room, it’s a lot more difficult to think about what would be essentially useful to you than to think what the rules are. That’s about love, and I think that’s what Butterfield tries to say in talking about passion. Teacher/student relationships are arenas for disrupting our addiction to dualism, and we are called upon to really strip ourselves down, to where we don’t have guides anymore. In real love, real union, or communion, there are no rules.

As a prominent black feminist, how difficult is it for women, especially other black feminists, to hear you say that your fundamental sense of yourself is as a seeker on the path? Does it evoke a sense of betrayal? I think so, certainly a few years ago it did. But feminists in general have come to rethink spirituality. Ten years ago if you talked about humility, people would say, I feel as a woman I’ve been humble enough, I don’t want to try to erase the ego—I’m trying to get an ego. But now, the achievements that women have made in all areas of life have brought home the reality that we are as corruptible as anybody else. That shared possibility of corruptibility makes us confront the realm of ego in a new way. We’ve gone past the period when the rhetoric of victimization within feminist thinking was so complete that the idea that women had agency, which could be asserted in destructive ways, could not be acknowledged. And some people still don’t want to hear it.

To what extent has the issue of victimization in feminism been diffused by the national obsession with—as you call it—victimage? In a culture of domination, preoccupation with victimage is inevitable.

And this keeps dualities locked in place? I used to believe that progressive people could critique the dualities and dissolve them through the process of deconstruction. But that turns out not to be true. With the resurgence of forms of black nationalism that say white people are bad, black people are good, we see an attachment to notions of inferiority. Dualities serve their own interests.

How does this come up for you in your daily life? Life was easier when I felt that I could trust another black person more than I could trust a white person. To face the reality that this is simply not so is a much harder way to live in the world. What’s scary to me now is to see so many people wanting to return to those simplistic choices. People of all persuasions are feeling that if I don’t have this dualism, I don’t have anything to hold on to. People concerned with dissolving these apparent dualities have to identify anchors to hold on to in the midst of fragmentation, in the midst of a loss of grounding.

Your anchor is love? Yes. Love and the understanding that things are always more complex than they seem. That’s more useful and more difficult than the idea that there is a right and wrong, or a good or bad, and you just decide what side you’re on.

We see this in your relationship with Thich Nhat Hanh. You quote him with obvious reverence, but not with blind devotion. You have also referred to gender-related problems with his teaching. When Nhat Hanh is talking about work or our engagement in social issues, his vision is so vast, so inclusive, so generous. But on questions of family and marriage and sex, we get the most conventional notion of what’s good. Celibacy is good or having a family is good. There’s nothing between celibacy and family life.

I’ve been puzzled by the same contradiction in his work. But I’ve wondered if it’s a contemporary pragmatic response to the lives of his students. One of the threads that I see in all his writing is a particular kind of memory of childhood that he holds to: a childhood of preawareness of anguish, one might say. He evokes the child as an aware being but it’s the child who has no anguish and no sense of horror. And in his romantization of the heterosexual family—which is always biased—it’s very clear that it remains biased in favor of the old order of patriarchy and hierarchy.

Have you ever met Thich Nhat Hanh? I’ve been afraid to. As long as I keep a distance from that thread, I can keep him—and I can critique myself on this—as a kind of perfect teacher. Reading about his attachment to certain sexist thinking in a book is one thing, but actually experiencing it at a gathering would be another thing. That would be sad for me. I want his wisdom to extend into his thinking about family and gender relations or sexuality, and I don’t see that.

Do you see it anywhere? Trungpa Rinpoche’s thinking is still the most progressive in terms of desire and sexuality. Whether he was able to live those theories out in their most expansive possibility is another thing. What I get from him and Merton, that I don’t get from Nhat Hanh, is a real willingness to think of pleasure as a potential site of spiritual awakening and enlightenment. Thich Nhat Hanh cuts off sensual pleasure from any continuum that would lead to desire and to sexuality.

In your interview with Andrea Juno (in Angry Women, Re/Search, 1992) you talk of having been a cross-dresser, which, for women is, among other possibilities, a foray into the dominant culture. How does it experiment with the deconstruction of the self and, simultaneously, with the patriarchy? I thought of it as an experience of erasure. When Joan of Arc erased herself as female, she was also trying to erase the self to which she was most attached. And her experience of cross-dressing was a path leading her away from the ego-identified self. She didn’t replace one attachment with another—”Now I’m the identity of a man.” It was more, “Now I’m away from the identity I was most attached to.”

This is the same kind of experimentation as using your grandmother’s name—bell hooks—for writing? I think so. It’s primarily about an idea of distance. The name “bell hooks” was a way for me to distance myself from the identity that I most cling to, which is Gloria Watkins, and to create this other self. Not dissimilar really to the new names that accompany all ordinations in Muslim, Buddhist, Catholic traditions. Everyone in my life calls me Gloria. When I do things that involve work, they will often speak of me as “bell,” but part of it has been a practice of not being attached to either of those.

As in: “I’m not trying to be bell hooks.” The point isn’t to stay fixed in any role, but to be committed to movement. That’s what I like about notions in Islamic mysticism that say, Are you ready to cut off your head? It’s like asking, Are you ready to make whatever move is necessary for union with the divine? And that those moves may be quite different from what people think they should be.

What would you say is the Buddhist priority? What are our moves? I think one goes more deeply into practice as action in the world and that’s what I think when I think about engaged Buddhism.

Are you making any distinctions here between Thich Nhat Hanh’s use of the expression “engaged Buddhism” and “liberation theology”? No. I like that the point of convergence of liberation theology, Islamic mysticism, and engaged Buddhism is the sense of love that leads to commitment and involvement with the world, and not a turning away from the world. A form of wisdom that I strive for is the ability to know what is needed at a given moment in time. When do I need to reside in that location of stillness and contemplation, and when do I need to get up off my ass and do whatever is needed to be done in terms of physical work, or engagement with others, or confrontation with others? I’m not interested in ranking one type of action over the other.

Why are so many other people? I think that it goes back to our relationship with pain. One of the mighty illusions that is constructed in the dailiness of life in our culture is that all pain is a negation of worthiness, that the real chosen people, the real worthy people, are the people that are most free from pain. Don’t you think that’s true?

That was a prevalent idea among white Buddhists when Buddhism took off in this culture in the sixties and seventies—that the teachings are about how not to suffer, rather than how best to deal with the inevitable suffering that life deals out. We see that denial in a lot of New Age thinking in the rhetoric that connects becoming more wealthy, more happy, and more free from all forms of pain with becoming more spiritual.

Are love and suffering the same? To be capable of love one has to be capable of suffering and of acknowledging one’s suffering. We all suffer, rich and poor. The fact is that when people have material privilege at the enormous expense of others, they live in a state of terror as well. It’s the unease of having to protect your gain, which then necessitates even greater control. That’s why we see fascism surfacing right now in Europe and the U.S., a compulsion to control. This phrase New World Order is so significant because it confirms everybody’s sense that life is out of control. And we are weakened by nihilism.

That’s what Cornel West writes about. Yes. Nihilism is a kind of disease that grips the mind and then grips people in fundamental ways, and can only be subverted by seizing the power that exists in chaos.

The power of self-agency? Absolutely. And collective agency, too, because of the idea—as in Nhat Hanh’s work—that the self necessarily survives through linkage with the collective community.

A lot of oppressed people seem to prefer to blame, rather than to relate to the teachings of mind and transformation of consciousness. Your work does not typify either the black or the female voice in America. But a lot of the young rap artists are saying the same thing, in a different way. I think KRS One and the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy are trying to say, We really are people of the mind, that black youth are not just creatures of the body. In a lot of contemporary music one hears a certain sense of anguish that is felt in the mind. Malcolm X is such a hero to certain rap musicians because he was totally focused on the mind. Black youth culture is very much aware of that but they are not sure where to go with it.

For all of your commitments to an integrated view, are there places of conflict between the political and spiritual? As a woman, as an African-American? Absolutely. The places of conflict are always there. Look at this whole question of sexual harassment and sexual violation. What’s so interesting is how much it conforms to very traditional notions of gender. In Buddhist practice, intimacy with the teacher is the space of potential violation.

In your own experience? In one of my earliest encounters with a Buddhist guide, he tried to have sex with me. I was infinitely more interested in what he had to say about Buddhism than I was in his body. Yet he was saying that the closer I got to his body, the closer I got to what he thought about Buddhism. This is fundamentally discouraging.

Thich Nhat Hanh talks about women in a very traditional way. When I read a book like Shambhala: Path of the Warrior (Shambhala Publications, 1984) I ask myself, Where am I located in this as a woman? Again, the mother is evoked in the traditional role of nurturer, and separate from the world of warriorship and lineage that is so clearly defined as male.

Women are particularly susceptible to abuse with regard to the spiritual qualities of surrender and humility. What do we do about that? That is tied to reshaping Buddhist practice so that one really sees fundamental change. We all have to have a lived practice. For example, if we see a female who is powerful yet humble, we can learn about the kind of humility that is empowering, and about a form of surrender that does not diminish one’s agency. But it seems to me that that “me” has to be altered in the very way we structure any kind of practice, any kind of community.

And whatever problems we encounter in the Buddhist communities must pale in comparison with those in the black communities? The collective black community does not allow women to become leaders in the same way we allowed Malcolm or Martin to spring up and be in a position of leadership. And nobody in the community wants to deal with that fact. There are a lot of women out there who are able to lead, and the problem is that people will not follow them.

Do you frame this around one central problem? The central problem for women is that you can’t give up the ego and the self if you haven’t established a sense of yourself as subject. It seems to me that questions of humility and surrender don’t even come in until one has something to give up.

I do think that women like myself have to integrate the processes by which we change, and speak about those processes more. Gloria Steinem, in Revolution from Within (Little Brown and Co., 1991) says that in part there are many women now with skills and resources, but if they still feel shaky in the deep inner core of being, they cannot move forward against patriarchy. This goes back to all I’ve been saying about victimization. A lot of black people with resources and skills are so convinced inwardly that they lack something, that they cannot move forward.

Can you tell us something of your own life that reveals how you arrived at your current understanding? It was a tremendous liberatory moment in my painful childhood, when I thought, I am more than my pain. In the great holocaust literature, particularly the Nazi holocaust literature, people say, All around me there was death and evil and slaughter of innocents, but I had to keep some sense of a transcendent world that proclaims we’re more than this evil, despite its power. When I’m genuinely victimized by racism in my daily life, I want to be able to name it, to name that it hurts me, to say that I’m victimized by it. But I don’t want to see that as all that I am.

Sartre’s two ways to enter the gas chamber: Free and not free. Yet, I must admit that when I read your essay on Anita Hill (in Black Looks, Southend Press, 1992), I was surprised at how hard you came down on her. Yes, but I never once tried to deny the reality that she was sexually harassed. At the same time I said she’s more than that sexual harassment. She’s also a political conservative who has totally allied herself with the white male supremacist patriarchy, just like Clarence Thomas has. She is anti-abortion and was pro-Bork, for example.

You also call into question her inability to take responsibility for what happened with Thomas. Even when she came forward, she was still saying on TV “other people urged me to come forth.” She was still presenting herself as a passive person, without agency, responding to other people. That bothered me. And I was disturbed that so many women identified with that. What I want to know is, where is her ability to say, I feel that this man should not have certain forms of power, and I wanted to come forward of my own free will and not because other people urged me to.

How do you explain Anita Hill’s popularity? I make bumper stickers in my mind. And one of them is “Everybody loves a woman who is a victim.” Would people love Anita Hill had she actually been able to block Clarence Thomas’ appointment? Would she then have been perceived as a woman who was too powerful? What actually catapulted her into stardom was the fact that she lost. That even though she came forward, even though she sacrificed a lot, she didn’t attain the desired goal. And this is absolutely in tune with the culture of domination. I remember reading a book on lying that said Americans are lying more and more in daily life, with simple things such as how are you feeling today, or what did you do today, who did you talk to on the phone? And I’m thinking, My god, if people cannot tell the truth about things that have absolutely no layer of risk, of danger, how do we expect people then to stand up in situations of crisis that are matters of life and death? To the degree, again, that people do not wish to experience pain, they will engage in denial. And denial, I think, is always a practice of narcissism because it’s always about protecting the self.

“I make bumper stickers in my mind. And one of them is ‘Everybody loves a woman who is a victim.’ Would people love Anita Hill had she actually been able to block Clarence Thomas’ appointment? What actually catapulted her into stardom was the fact that she lost.”

Again, that’s why I like Butterfield’s piece, because he says that these narratives of victimage go back to the self, and that denial protects what people think has to be protected and guarded.

And there are also real abuses. How can we deal with that? What was problematic for me about Butterfield’s piece was that I don’t think he gave us the whole picture in the sense that he wasn’t really willing to acknowledge those real abuses. It’s a lot harder to frame your argument if you say, Yes, exploitation occurs, but something else occurs at the same time. Yes, racism occurs, but something else occurs at the same time. How is one to get in touch with all of those different things?

But how do you make a distinction when, for example, someone turns to you and says, “You feel victimized? That’s your problem.” The Zen communities functioned this way for years in response to individual complaints. People are genuinely exploited, but that reality doesn’t take away from the many, many instances where people give up their own agency and, in that way, help create a setting for exploitation. Only by holding on to the sense that we can never be completely dehumanized by “others” can we create a redemptive model. If you’re attached to being a victim, there is no hope. One has to work out points of blockage, or victimage to agency, and from there build a collective process that can change an institution and can change a societal direction.

Let’s take a version of that in Buddhism. The gender problems with Thich Nhat Hanh, for example, are not “abuses” but there’s an attitude. Do you “confront” the teacher? If there was more of a collective call on the part of students to say to a teacher, “We are concerned that there are all these other areas that we see changes and growth in your thought, but when it comes to questions of gender and family, we don’t.” I think a real problem is how we frame devotion to the teacher. And the question of questioning. That’s something that has to be done more collectively. I think that if an individual alone tries to question, they get crushed, sometimes not just by the teacher, but by other students.

What is the dynamic of victimization in our society? A culture of domination like ours says to people: There is nothing in you that is of value, everything of value is outside you and must be acquired. The tremendous message in this culture is one of devaluation. Low self-esteem is a national epidemic and victimization is the flip side of domination.

To what extent is your work considered a contradiction by progressive blacks? Not that much. Because people hear me saying revolution must begin with the self, but it has to be united with some kind of social vision.

“A culture of domination like ours says to people: There is nothing in you that is of value, everything of value is outside you and must be acquired.”

But I see many people deeply engaged in complicity with the very structures of domination they critique. And I think that that is an illusion. It’s true that often, let’s say, when I talk about theory, I do have to argue for the fact that theory making or certain forms of critical thinking are essential to a process of change because people have been led to believe you can have change without contemplation.

To a lot of people they would say, You can use your rage. I feel that, yes, I can use my rage, but only if there’s something else there with that rage.

Take the Rodney King case. The verdict comes down, the cops are not guilty. How do you go from there to not feeling victimized? I don’t think it’s that you don’t feel victimized. You acknowledge that you’re being victimized. But the question becomes, is rage the only or the most appropriate response? What would people have thought if rather than black people exploding in rage about the Rodney King incident, if there had been a week of silence? Something that would have just so unsettled people’s stereotypes about black people.

One of the things that characterized the riots was the tremendous empathy across the country for King. The sad thing is that the empathy came from a sense of total victimization.

So they are victimized but they have self-agency. Right. I think it serves the interest of domination if the only way people can respond to victimage is rage. Because then they really are just mirroring the very conditions that brought them into victimization. Violence. The conquering of other people’s territory. If we talk about the burning down of other people’s property as a takeover, is that different from what the U.S. did in Grenada or Iraq? It’s not a stepping outside of the program, it’s a mirroring back, and that’s why I think so many white people and masses of other groups felt sympathy. Because the other side of total victimage is rage.

Victimage… I was thinking about the victim identity. If you look at the early feminist movement and the women who were seeing themselves the most as complete victims also had this blind rage, because those two things go together. That’s why it’s so dangerous, because then you’re not operating outside the forces of domination at all. You’re still tied intimately to that psychology of domination.

So consciousness is the only way to transmute the forces of domination. The only way. There is no change without contemplation. The whole image of Buddha under the Bodhi tree says here is an action taking place that may not appear to be a meaningful action.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.