The documentary Aware: Glimpses of Consciousness begins with the Indian parable of six blind men sent out into the night to assess the source of a commotion outside the city walls. Each returns with a different interpretation—a snake, a rope, a stone wall—based on what they felt: all different parts of the same elephant. The documentary’s closing shot is of a young elephant playing along the banks of a river, tossing around a tire and splashing in the mud. In the interim, the film follows six experts grappling with questions of consciousness, mystical experience, and death from varied perspectives. Are these experts—who include a neuroscientist, a Mayan healer, and a Buddhist monk—like the blind men, grasping at different parts of the elephant? Or are they all circling the playful, muddy, and ineffable essence itself?

Questions surrounding consciousness have been around for, well, about as long as we’ve been conscious. It’s heady territory (literally and figuratively). For all the heavy lifting consciousness does as a concept, it becomes impossibly light when you attempt to pin it to a definition. This subject-object dissonance between what consciousness feels like and what it actually is is known as the mind-body problem. As Christof Koch, the chief scientist and president of the Allen Institute for Brain Science and the first expert we meet in Aware, puts it, “How do you turn the waters of the brain into the wine of our conscious experience?” In other words, how can a specific arrangement of physical matter result in sentience—the ability to perceive—and perhaps more importantly, sentiment—the sense that our perceptions not only belong to us but mean something?

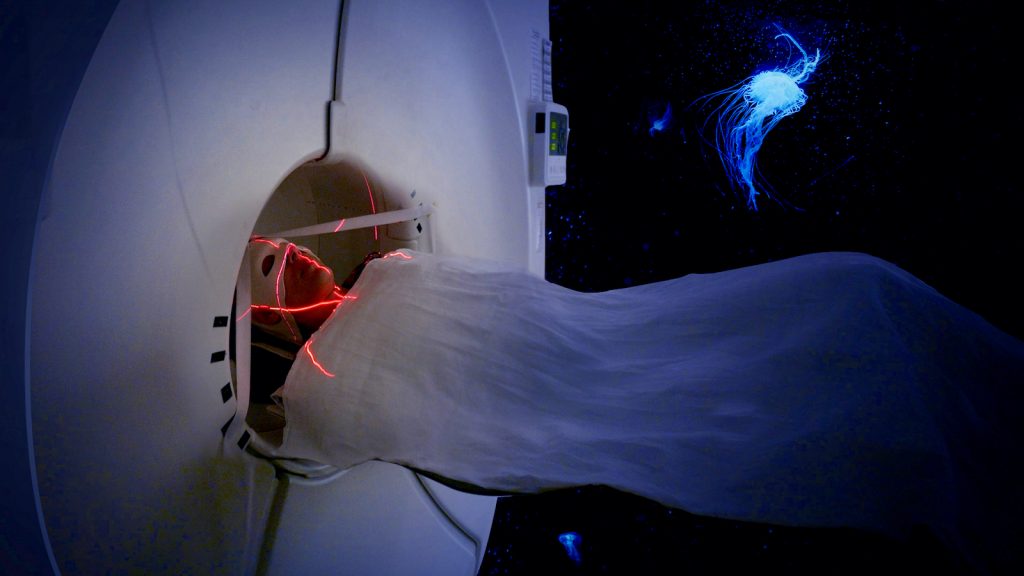

Aware poses these questions at a time of notable dovetailing among varied strands of research on the brain and consciousness, which has opened the doors to topics like plant consciousness and drug-induced mystical experiences and allowed researchers to take seriously the kinds of assertions that might have once seemed flighty to even the most sagacious dorm room pontificator. In one of the strangest scenes in the movie, Justine Fritz, a participant in a psilocybin study (the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms”) at the John Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, answers questions from a researcher on a scale of 1-10 while tripping under the buzzing brightness of a PET scanner.

“Distance from reality?” the researcher asks.

“Six,” Fritz answers.

“Pure being and pure awareness?”

“Five.”

“A fusion of personal self into a larger whole?”

“Four.”

Later the researcher relates the numbers to another researcher, remarking with muted excitement, “Eight for timelessness.”

“We may have a touch of a mystical experience here,” he responds.

Summarizing the window such drug-induced mystical experiences provide, Roland R. Griffiths, the gently paternal Director of the John Hopkins Lab, explains, “Meditation is the tried and true course for understanding the nature of mind, and psilocybin is the crash course.” This is the kind of statement that tends to irk both scientists and Buddhists alike, yet as Michael Pollan detailed in How to Change Your Mind, a swath of research on the impacts of both meditation and psychedelic experiences on the brain shows undeniable overlaps, particularly in the quieting of the Default Mode Network, a region that seems primarily responsible for propping up the echo chamber of the ego. As this network quiets, one tends to become more in tune with the immediate, and feel a deeper and more open connection to experience that is not walled off by a sense of self.

The most powerful example of this in Aware comes from Loyola philosophy professor Richard Boothby, who participated in a psilocybin session at John Hopkins as a self-described skeptic in the aftermath of his son’s suicide, and had what he describes as a “completely life-changing experience.”

Boothby recalls thinking of his son during his session, and the revelations that it triggered. “I thought to myself maybe this is why this life is so filled with failures and tragedies and losses. That love requires these failures. . . Love, perhaps in this very mysterious way, requires death in order to sort of purify itself.” Boothby knows full well how cheesy this brand of philosophizing can sound: “I would have regarded it in another time and place as a kind of, not just silly and religious thought, but maybe almost a despicable thought; of making light of what is terrible and tragic, of sugarcoating and making appear acceptable what isn’t acceptable.” Yet it is hard not to believe how significant Boothby’s experience was, because as he speaks of reconciling with unimaginable loss, tears stream down his cheeks. In the end it is the subject, rather than any objective measures, that tells the story.

***

It turns out this subject-object dissonance is not only a challenge for philosophers and scientists to capture but one for filmmakers as well. As viewers we can’t feel what the experts and research participants understand, and so Aware must contend with this gap in what is conveyed on the screen and what the subjects know in their hearts, minds, and bones. In order to minimize this distance, the film deftly employs moving and ethereal scores by cellist and composer Zoë Keating, and the ethereal imagery to match, from the sun glinting through trees to monks chanting and whales swimming in tandem. The landscapes featured in the film are mountains, monasteries, oceans, and laboratories; the hallways of the profound.

I was left wondering how the lay viewer, at home in the city or suburbs, far away from chanting monks and floating whales, might interpret such visuals. It’s easy to feel a gap between the profound and the ordinary, and a sense that what is meaningful will occur either way outside, in the kind of nature one can rarely access, or way inside, through the kind of experience one can rarely achieve. How might we begin to achieve the radical openness described by mystics if our couches feel so removed from the richness of reality? One might argue that the true power of psilocybin, meditation, communion with nature, and illuminating science is collapsing this distance.

Still, the goal of the film is to evoke, and it does it well. To talk about consciousness is necessarily to dance around the subject—or subjectivity itself. Monica Gagliano PhD, who studies plant behavior and cognition and is one of the experts profiled in Aware, describes consciousness as an ocean, whereas Matthieu Ricard, the Buddhist monk, describes it as a river. In the end it is a subject too big to grasp, not necessarily because of a failure of imagination, science, or filmmaking, but because the elephant in its entirety is ungraspable. Still, although one doesn’t quite get the whole picture, one is left feeling a little more whole. As Justine Fritz explained of her psilocybin session, the experience furthered her belief in the “connective thread that is binding all of us in the world.” Aware manages to further that belief as well, bringing subject and object, sentiment and science, and even couch and consciousness closer together.

♦

Join Tricycle and Area 23a on Wednesday, November 10 at 7:30 p.m. EST / 4:30pm PST for the livestream premiere of AWARE: Glimpses of Consciousness. Buy your ticket now.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.