Every novice meditator who has ever been instructed to sit and follow the breath knows all too well the maddening elusiveness of our respiratory cycle. We find the breath to be a most intimate yet ephemeral companion—closer than close, touched for a moment and then lost amid a swirl of thought and sensation.

The breath is ever-present, the very essence of life, and it is an ongoing exchange between inside and outside, self and other. So it is not surprising that references to the breath abound in diverse spiritual traditions around the world. For Buddhists, the Pali Canon’s Anapanasati Sutta—sometimes translated as the “Breath-Mindfulness Discourse”—is a foundational meditation instruction.

With Breath Taking, an exhibit of drawings, installations, photographs, sculpture, and video on display at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe until September 5, 2021, a diverse group of visual artists explore some innovative methods for rendering breath palpable and making the intangible tangible. Each of their contributions invites us to reconsider our own relationship with this most fundamental activity.

The photo images presented in Just Breathe are disarmingly simple. Artist Linda Alterwitz asked a dozen participants to lie on the ground with cameras on their chests pointed at the night sky, set for 30-second exposures. The movement of each person’s breathing creates a unique pattern: in some of the prints the tracks of the stars are discernible, while in others an abstract pattern of light emerges. Despite the differences, each is a faithful record of the individual’s experience.

New York artist Stuart Allen’s still and video images of iridescent soap bubbles floating against a sun-drenched sky are both mesmerizingly beautiful and thought-provoking. We know that each fragile orb represents a captive human breath that will return to the atmosphere when the bubble bursts, but in this brief interval everything is perfect, just as it is. Nearby, Allen has also mounted an installation of 35 box kites—weightless white cubes suspended in midair that gently respond to invisible air currents.

In a fine example of process art, Alison Keogh captures the rhythm of her own exhalations with finely brushed sumi ink on paper, generating densely intricate wavelike patterns. The close connection between breath and brushwork may call to mind the enso—the iconic circle brushed on rice paper by a Zen master as a manifestation of an awakened mind.

With Breath 2, draped silk wall hangings dyed in the pale blues and pinks of the evening sky are so finely woven that they undulate slightly in the air displaced by each passerby. They are the handiwork of Albuquerque artist Marietta Patricia Leis, who envisions air as “a common denominator that unites and equalizes us.”

Cynthia Greig’s Breath Scan Portraits portray another sort of interaction between air and the environment. She invites people to exhale onto the glass of a flatbed scanner, which captures the appearance of the condensed water vapor before it evaporates. Each black-and-white print renders a distinctive ghostlike shape, visual proof that no two breaths are alike.

For all the meditative tranquility evoked by these works, some elements of the exhibit directly address the twin pandemics that transfixed and transformed our world in the past 18 months.

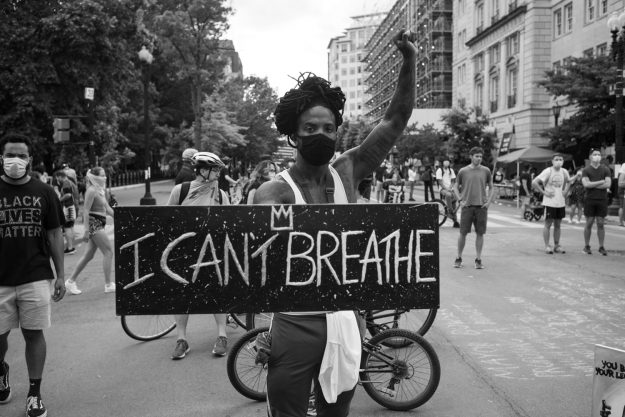

The SARS-CoV-2 infection, the virus that causes COVID-19, is most terrifying for its relentless assault on the lungs, scarring the tissue so severely that victims are left gasping for air or cast into a medically induced coma while connected to a ventilator. Equally terrifying is the metastasizing wave of police violence in the United States, in which enforcers of the law have repeatedly been caught literally squeezing the life out of their fellow citizens.

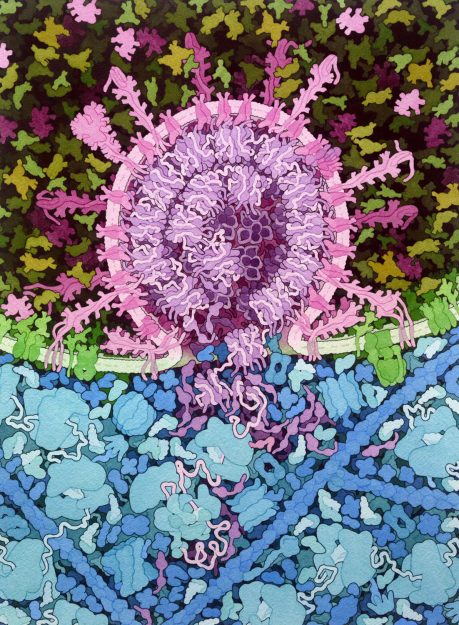

These ominous events can be referenced with deceptive ordinariness. Biologist David Goodsell’s watercolor portraits of the coronavirus represent the spike protein-studded microbe in stunning detail—as if enlarged two million times. There is a strange beauty to the deadly pathogen, depicted with a near-psychedelic intricacy that would look at home on a Grateful Dead poster.

Chimayo, New Mexico photographer Don J. Usner opts for a stark black-and-white documentary approach, capturing his mostly Hispanic mask-wearing neighbors in various outdoor settings around Northern New Mexico. Each image is an astonishing reminder of how quickly pandemic protections became a routine part of daily life.

A photo print from the museum’s permanent collection made by Will Wilson depicts three overlapping views of a Diné (Navajo) man wearing a breathing apparatus as he offers cornmeal as part of his morning prayers at the rim of the Grand Canyon. The hazmat reference, juxtaposed with the breathtaking natural setting, evokes the central role of harmony in Navajo spirituality, even in the midst of a disharmonious world.

More unsettling are two works from Jill O’Bryan, who devised a method for making a mark on paper to coincide with each inhalation and exhalation while contemplating the asphyxiation of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. In one, she applied “holy dirt” taken from El Santuario de Chimayó (a Roman Catholic church in Chimayó and a famous pilgrimage site) to rice paper for eight minutes and 46 seconds—the agonizing interval in which an officer knelt on Floyd’s neck. The other, using graphite for a similar duration, yields a pair of glowering blackened shapes.

Taken as a whole, Breath Taking asks us to recollect and reconsider a primal experience that most of us take for granted. And in its own way it serves as a powerful meditation on presence, absence, and all that lies between.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.