A few years ago, the gallerist of a premier art space in Milan told Italian multidisciplinary artist Michela Martello that representing women was a real challenge.

“Women don’t sell,” Martello recalled him saying in a frank conversation.

Flash forward to May 2018, and Martello and a contingent of Italian artists are presenting “Super S.H.E,” the first all-female group show at Giovanni Bonelli Gallery.

What changed? Martello—a fine artist turned “street-art guru” whose work is influenced by classical Italian painting, Buddhist motifs, and graffiti—told Tricycle that she and other women have been making significant gains in the art world. And now galleries and museums are trying to catch up to the culture, she said.

Dismantling stereotypes of women throughout history will be a common theme in several solo and group shows that Martello is participating in this summer, including Consequential Stranger in Raleigh, North Carolina, where Martello is displaying her Buddhist spin on Botticelli’s Renaissance masterpiece, The Birth of Venus.

Her version of Venus is a female wisdom deity known as a dakini, meaning “sky dancer” or literally “she who moves through space.” Martello’s dakini-Venus is gestating a Tibetan snow lion, a symbol of fearlessness and a reference to Shakyamuni Buddha, while crushing a medieval Gothic demon.

“She’s taking steps toward the sky and is not afraid to occupy the entire canvas. Nowadays, women can stretch themselves and are empowered to do so,” Martello said, reflecting on the current climate. “A few years ago, especially in Italy, this was still unthinkable.”

Visualizing images of empowered female figures is an important part of Martello’s personal practice and art-making process. “But you certainly don’t have to be a woman, a Buddhist, or an iconography expert to relate to dakini energy,” she said.

Related: Dancing with the Divine Feminine

Also featured in the Raleigh exhibit (which opened this April and will run through June 1) are what appear to be pottery relics from Ancient Rome. On closer look, the clay shards are, in fact, broken fragments of a female body: a brain, eyes, ears, teeth, heart, lungs, intestines, uterus, and breasts, along with a strand of DNA. The collection nods to the Buddhist idea that we are a sum of our parts rather than an essentialized, fixed self.

In many ways, Future is Goddess and the ceramic relics merge Martello’s Italian and Buddhist visual vocabulary, but this coupling hasn’t always come so easily.

Trained as an illustrator at the Europe Institute of Design, Martello felt that the traditional techniques and methods taught in school could be incredibly rigid, especially when it came to depictions of women.

“My style has always been somewhat oppositional and spontaneous,” she said. Often, her teachers commented that her subjects were either too spiritual or ethereal. But Martello believes that arts education in Italy is beginning to break from its “highly conceptual and often chauvinistic art forms.”

In the nineties, soon after meeting her Buddhist teacher, the late Tibetan master Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, Martello moved to New York City, where she found the art scene more open to transgressive thinking.

“In Italy, I would have struggled to assert myself. But thanks to institutions like Pen and Brush, a 125-year-old nonprofit in Manhattan, women in the arts are supported in an ongoing way.

“When we lift each other up,” she added, “stereotypes become old ghosts.”

Related: Nasty Women Meditation

Martello’s large-scale murals, sculptures, and collages have since headlined at several feminist exhibits and public arts installations. Many of her creations are made by repurposing quilts, US Army tents, vintage fabrics, pages from Shakespeare plays, animal skulls, and human hair. The resulting pieces are as inventive as they are provocative.

Women breaking down constructs and taking flight is the theme of Wings to Fly, a Frida Kahlo-inspired exhibit that pays tribute to the Mexican painter and pop-feminist icon. The modest showcase, on view at the PBX Gallery in downtown Brooklyn through June 9, features artwork by Martello and Indian-American Jewish painter Siona Benjamin, along with select pieces from others, who use art to think critically about their national, religious, and gender identities.

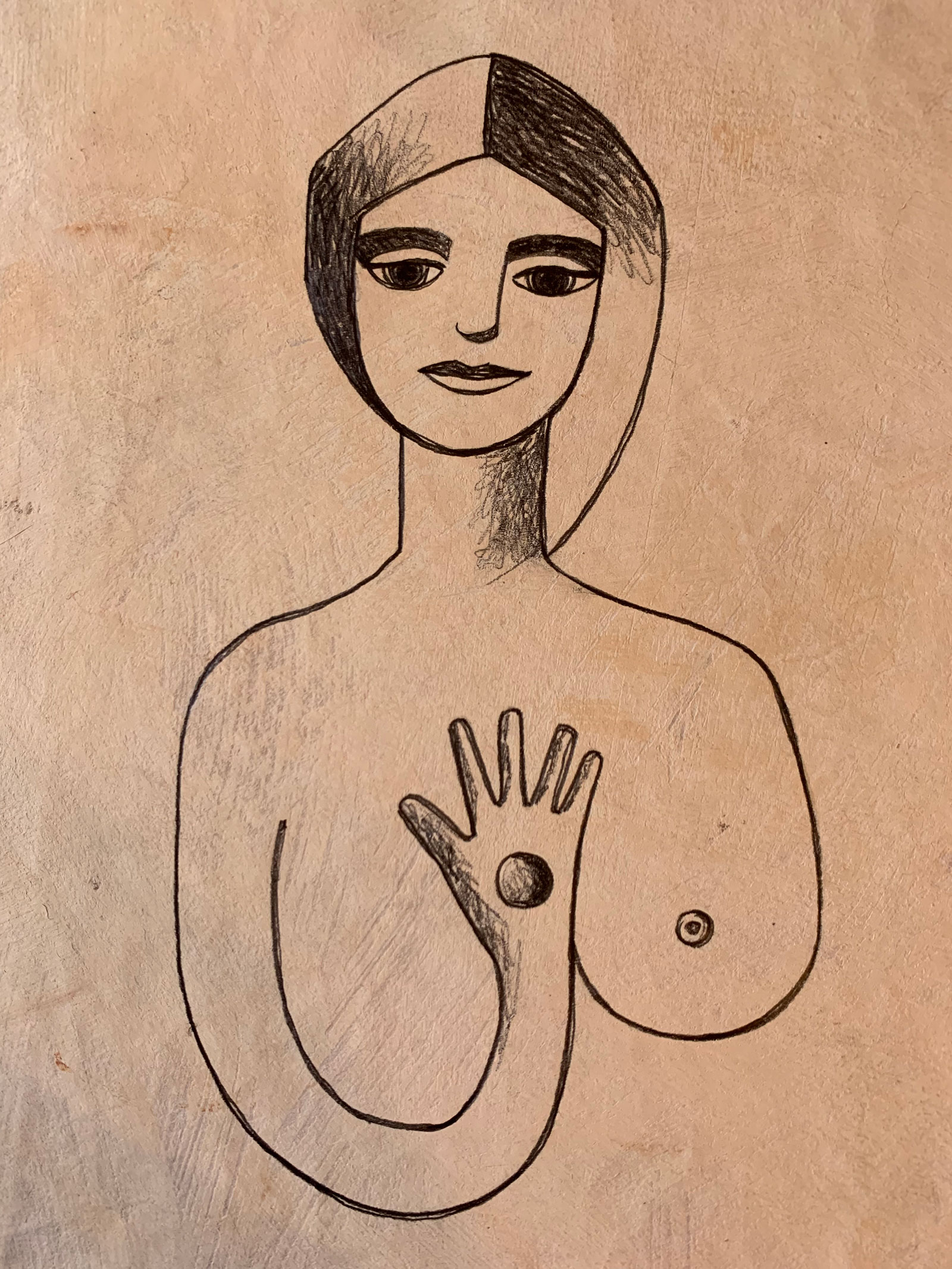

With Outsider, a self-portrait akin to Kahlo’s contour drawings, Martello explores and challenges the way we craft our own images and identities around the often constrictive roles that we are expected to perform.

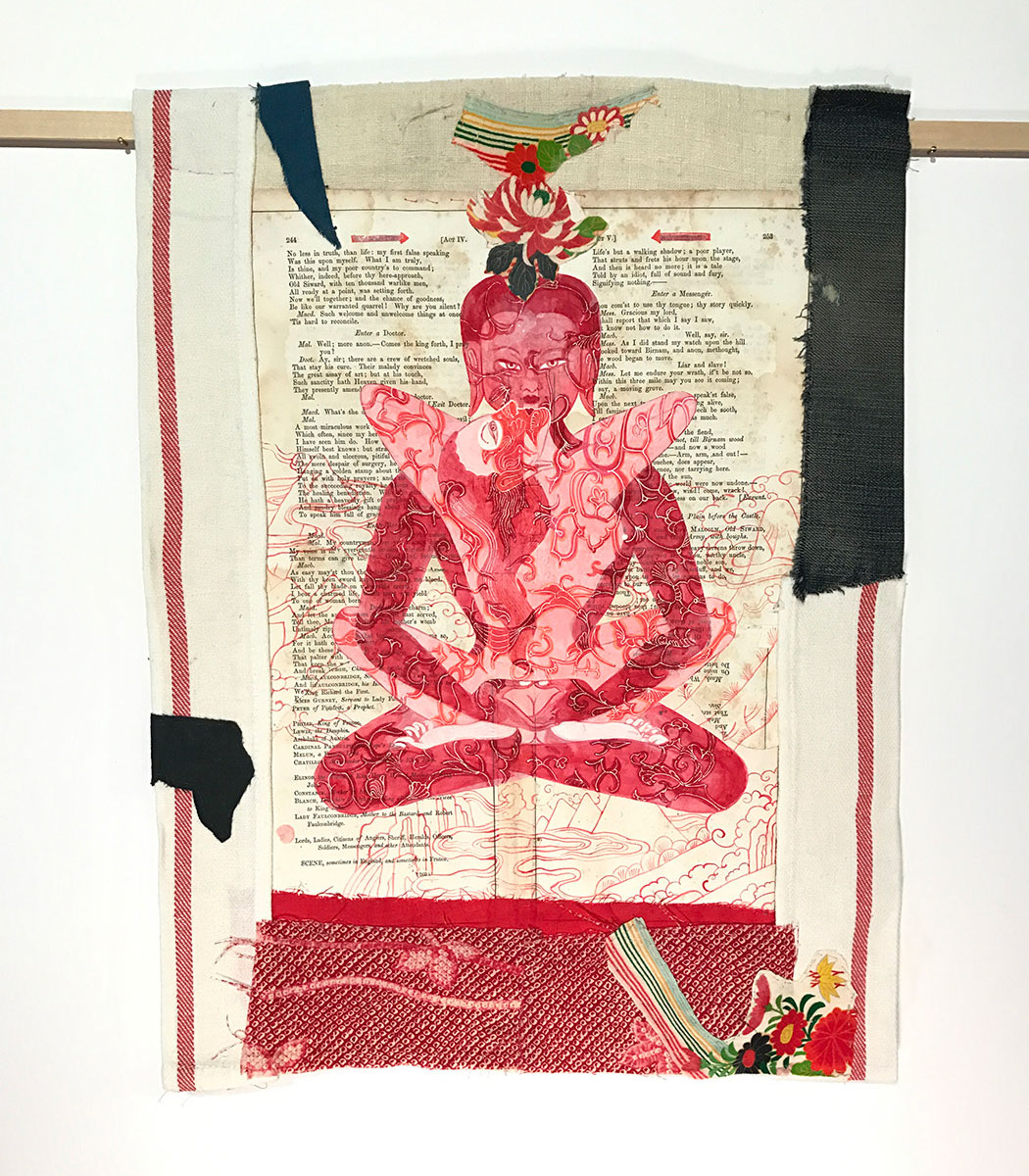

In another of Martello’s works at Wings to Fly, pages from Shakespeare’s King John and kimono fabric are stitched together to form the body and brocade of Yabyum, a nontraditional thangka, or Buddhist scroll painting. At its center, a male and female deity are locked in sexual embrace—a Vajrayana visual device that’s often misunderstood as an obscene display of eroticism. The symbolic union of the tantric pair signifies two aspects of enlightenment—wisdom and compassion—coming together, and the image is meant to uproot the sources of ignorance and suffering.

Martello explained that sitting with this and other Buddhist imagery is part of her practice, which she turns to when she gets bogged down by discursive thoughts in order to gain some perspective and reestablish her balance.

Together, Buddhism and feminism have led Martello to discover hidden parts of herself that manifest during the creative process. “When I’m making art, I can look honestly at myself, confront the shadows and insecurities, and eventually integrate their opposites into my life and work,” she said.

In both her art and Buddhist practice, doubt plays a key role in her ability to work through anger, depression, and creative blocks. On one of her first retreats with Namkhai Norbu at Merigar West, the Dzogchen center he founded in Tuscany, Martello was drowning in uncertainty. At the time, she was in her early 30s, unmarried, and without children.

“It can be difficult to talk openly with other women about pregnancy, child-rearing, and motherhood. Doubting is seen as a sign of weakness, when really it’s the opposite,” she said.

Raising questions around femininity and womanhood is what spurred Martello to produce a series of ceramic dolls, a handful of which are in the Raleigh exhibit. Not on display is Eva, a doll with a dark hole where her womb would be and the words I am not sure I want to have children in this life printed on her Victorian-style dress.

“Investigating the mind is always risky, yet Eva is celebrating doubts,” Martello explained.

Likewise, questioning the norms we inherit as individuals and societies can be uncomfortable, painful, and destructive, but it can also create something beautiful.

“I take refuge in doubt,” Martello went on. “Without it, I couldn’t grow.”

Michela Martello’s street art, textiles, and ceramics will be showcased with Parlor Gallery this June through September as part of their Wooden Walls Project in Asbury Park, New Jersey.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.