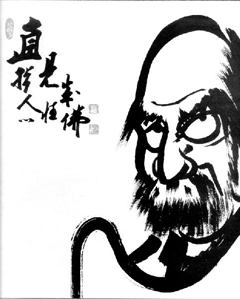

Although Bodhidharma is honored as the “First Ancestor” of Zen Buddhism in China, historians know well that Zen not only preceded Bodhidharma, it was also widely practiced centuries before his arrival. So how did Bodhidharma acquire the honored title of “The First”?

The foreign Parthian monk An Shigao is credited with introducing Zen to China in the 2nd century, roughly 300 years before Bodhidharma arrived in China. Plenty of evidence indicates that Zen gained popularity soon thereafter, with historical records indicating that Zen flourished in China’s Northern Liang Dynasty at least 50 years before Bodhidharma came on the scene.

Was there something different about Bodhidharma’s meditation practice that led to his special status? The historical record offers scant evidence to support such a claim. While it’s true that Bodhidharma was one of the early expounders of the Lankavatara Sutra—an important Yogacara text that influenced Zen—he was preceded by another “Lankavatara Master” named Gunabhadra, who is referred to as Bodhidharma’s teacher in an early, relatively reliable text.

Was there something different about Bodhidharma’s meditation practice that led to his special status? The historical record offers scant evidence to support such a claim. While it’s true that Bodhidharma was one of the early expounders of the Lankavatara Sutra—an important Yogacara text that influenced Zen—he was preceded by another “Lankavatara Master” named Gunabhadra, who is referred to as Bodhidharma’s teacher in an early, relatively reliable text.

The key might simply be that Bodhidharma was, as reports would corroborate, a dynamic, influential expounder of dharma. The best account we have of his life claims that “all who heard him were awakened.” Textual evidence suggests that Bodhidharma used the famous “Mu” koan long before it became associated with Zen master Zhaozhou, who was born hundreds of years later. It’s possible that this in combination with Bodhidharma’s charisma gave rise to his “First Ancestor” title.

Old memorials recently unearthed at Bodhidharma’s legendary burial place tell a new story that suggests that Bodhidharma’s status came to him long after he had died. During the An Lushan rebellion—a revolt that nearly destroyed the great Tang Dynasty around the year 755 AD—the Tang military commander, Guo Ziyi, prayed at Bodhidharma’s temple before engaging in a critical battle against rebel forces, asking the spirit of the sage for assistance. He subsequently won key battles and saved the dynasty, inspiring the Tang emperor to pay special tribute and honor to Bodhidharma and his burial place.

There is yet another possibility—one that I argue in Tracking Bodhidharma—that pulls from historical evidence to suggest that Bodhidharma and his early followers earned fame for their avoidance of the phenomenon of “Imperial Buddhism” represented by Emperor Wu, the “Bodhisattva Emperor” of the southern Liang Dynasty. In this figuration, Bodhidharma achieved popularity for his resistance to the usurpation of the Buddhist religion by China’s rulers. In other words, he became famous for being a rebel.

—Andy Ferguson

This post is part of author and scholar Andy Ferguson’s new “Consider the Source” series. As an old Chinese saying goes, “When drinking water, consider the source.” In the coming weeks, Ferguson will ask and answer seemingly simple (but in the end, profound) questions about the “source” of East Asian Buddhism, weaving a tale of both spiritual inspiration and political intrigue.

This fall, Tricycle will be traveling to the source itself, China, in a special pilgrimage led by Ferguson and abbot of the Village Zendo Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara. Want to come with us? Click here for more information.

Ferguson is the author of Zen’s Chinese Heritage: The Masters and their Teachings, which is used widely by Western Zen teachers, and Tracking Bodhidharma, which offers a wealth of new information about the founder of Chinese Zen Buddhism.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.