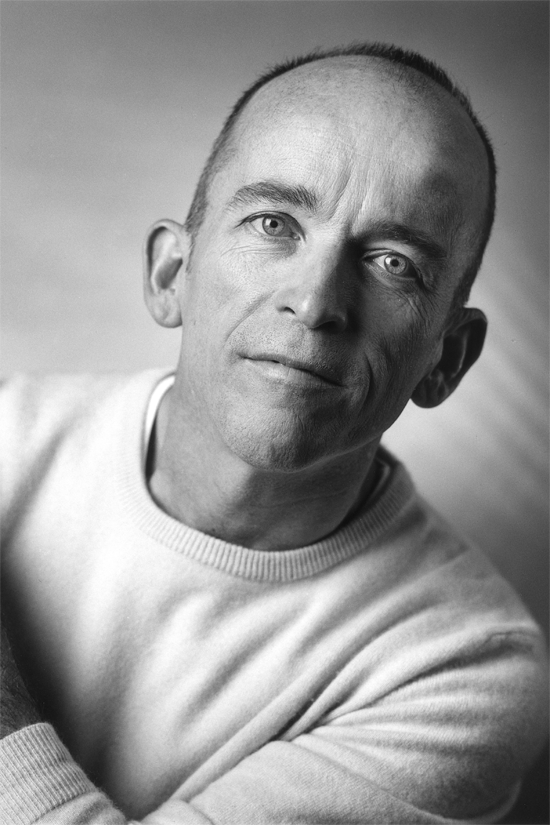

On an autumn afternoon, poet Mark Doty arrived at the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care to join its founders, Koshin Paley Ellison and Robert Chodo Campbell, in a conversation spanning grief, loss, attention, aging, and death.

Doty has published five volumes of nonfiction prose and eight books of poems, including Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems, which won the National Book Award for Poetry in 2008. His poems have been widely anthologized and have also appeared in such magazines as The Atlantic Monthly, The London Review of Books, Ploughshares, Poetry, The New Yorker, and, of course, Tricycle.

Doty lives between Manhattan and Long Island, and teaches at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. He has two books forthcoming: a new volume of poems entitled Deep Lane and a prose meditation on Walt Whitman.

—Robert Chodo Campbell and Koshin Paley Ellison

Koshin Paley Ellison: In Zen Buddhism, there is great value given to the exquisite fleeting nature of reality. In the evening gatha, we chant, “Let me respectfully remind you, life and death are of supreme importance. Time swiftly passes by and opportunity is lost. Let each of us strive to awaken, awaken! Do not squander your life!” Your poetry never fails to remind us of that chant.

Mark Doty: We’re face to face, every moment, with a world in flux—people, animals, everything that lives, coming into being and passing out again. All you have to do is sit down and look at practically anything in the natural world—clouds, the shifting pattern of sky seen through the leaves of the tree in front of my building on 16th St.—and it’s clear that nothing is fixed, and there’s no way to hold on to any moment. That’s easy to accept that when it comes to leaves moving in the wind, and much, much harder when it comes to people.

Mark Doty: We’re face to face, every moment, with a world in flux—people, animals, everything that lives, coming into being and passing out again. All you have to do is sit down and look at practically anything in the natural world—clouds, the shifting pattern of sky seen through the leaves of the tree in front of my building on 16th St.—and it’s clear that nothing is fixed, and there’s no way to hold on to any moment. That’s easy to accept that when it comes to leaves moving in the wind, and much, much harder when it comes to people.

The poem I think you’re referring to, “Mercy on Broadway,” was written a couple of years after the death of my partner, Wally Roberts. We’d been together almost a dozen years, and I could never have imagined that an epidemic would take him away. I thought we’d probably be together all our lives, and when he was gone I couldn’t imagine myself being able to love again. I remember distinctly seeing lovers in the street, couples touching or holding hands and thinking, Don’t they know? Where could love lead except to disaster?

Koshin Paley Ellison: But that poem takes such a different direction!

Mark Doty: It was about a year and a half later when I found myself beginning to care rather more than I’d expected for a friend whom I’d come to see in a new light. I was walking on Broadway one day in SoHo and came upon an Asian woman who was sitting on the sidewalk selling, of all things, tiny green turtles. She had them contained in a big white enamel bowl, and the little things were climbing over each other trying to get out, then sliding back down into the bowl again once they made it a ways up toward the rim. They were so beautiful—brilliantly green—and seemed so absurdly fragile; how could anything that tiny make it in New York City? I couldn’t forget them, and later found myself beginning to describe them. That’s how poems usually start for me: I begin with a description of some little thing that’s moved or interested me, and then, if I’m lucky, the process of writing teaches me why whatever it is matters. The turtles were such a potent image of ourselves: our incredible human persistence despite our frailty. We want to connect, to love, to move forward—we will climb up the sides of that bowl no matter what!

Robert Chodo Campbell: In the recent film written by Cormac McCarthy, The Counselor, he writes that grief has no value. Can you speak about the value of grief in your personal and poetic life?

MD: Grief does not seem to me to be a choice. Whether or not you think grief has value, you will lose what matters to you. The world will break your heart. So I think we’d better look at what grief might offer us. It’s like what Rilke says about self-doubt: it is not going to go away, and therefore you need to think about how it might become your ally.

Grief might be, in some ways, the long aftermath of love, the internal work of knowing, holding, more fully valuing what we have lost. I am always flummoxed and a bit amazed by the prevalence of the notion of “letting go.” Do we let go of the dead? Do we actually relinquish the connections and bonds that have been shaped? Or is it more like those bonds remain a part of us, become more internal? I think one’s wounds are ultimately so essentially a part of who one is that the self would be unrecognizable without them.

* * *

The Embrace

You weren’t well or really ill yet either;

just a little tired, your handsomeness

tinged by grief or anticipation, which brought

to your face a thoughtful, deepening grace.

I didn’t for a moment doubt you were dead.

I knew that to be true still, even in the dream.

You’d been out—at work maybe?—

having a good day, almost energetic.

We seemed to be moving from some old house

where we’d lived, boxes everywhere, things

in disarray: that was the story of my dream,

but even asleep I was shocked out of the narrative

by your face, the physical fact of your face:

inches from mine, smooth-shaven, loving, alert.

Why so difficult, remembering the actual look

of you? Without a photograph, without strain?

So when I saw your unguarded, reliable face,

your unmistakable gaze opening all the warmth

and clarity of you—warm brown tea—we held

each other for the time the dream allowed.

Bless you. You came back, so I could see you

once more, plainly, so I could rest against you

without thinking this happiness lessened anything,

without thinking you were alive again.

* * *

KPE: Can you talk about your relationship with Wally and, in particular, your poem about his visitation in “The Embrace”? What significance did it hold for you that you knew him to be dead even in your dream?

MD: Wally had a spontaneity about him, a genuineness and sweetness that I think everyone around him felt. He was a window designer by trade, and thus he was one of those gay men who could arrange a couple of objects, drape some fabric, shine the light in this direction and—astonishment!—make things immediately beautiful. The boy in him was close to the surface; he loved toys and dogs and kids. He was a person you’d very soon come to trust all the way to the core.

He was very ill for the last year of his life, living with a viral brain infection that people with very suppressed immune systems are susceptible to. Ironically, it’s a condition that pretty much no longer exists, since protease inhibitors have erased it, at least in the first world. There was no treatment, so he stayed at home in a bed in the center of the living room, cats and dogs and friends around him, and he died supported and cared for by people who couldn’t have loved him more.

After his death, there was a time when I had this awful experience of being unable to summon the memory of his face. This is probably not uncommon. When you live with someone closely, they become a part of your subjectivity in a way, and you don’t stand back and fix their image in your mind’s eye as you might otherwise. I was terrified that I had lost him again, in a new way. And then the kindest, most vivid dream came to me: there he was, utterly clear, physically present, all right. And I knew he was dead, even then. If I hadn’t, I’d have had to wake up and lose him all over again. The kindness of the dream lay in its duality: he was present, and he was gone.

RCC: In your elegy to Wally in your memoir, Heaven’s Coast, there is a moment when Wally reaches for your golden retriever. Can you speak about this moment?

MD: We had an older, sleepy dog we loved, but late in his life Wally wanted another. He was somewhat childlike, as a result of his condition, and almost completely in the present. He’d watch an episode of The Golden Girls and laugh and laugh, and then he’d watch it again immediately and laugh just as much because he had no memory of having just seen it.

I brought a young, rowdy golden retriever home from the animal shelter. In some ways it was a crazy thing to do, but Wally loved him. Just a few days before he died, I saw him reach out toward the sleeping dog on the bed beside him. His hand moved very slowly toward Beau—Wally couldn’t even feed himself then, but he wanted to touch that new, eager life; he wanted to participate—and I took a photo of that gesture because I wanted to keep it always. That was my love, a man leaving the world without bitterness, with a delight in the presence of a fresh, beautiful life, even then.

Talk about a spiritual lesson! If he could find that generosity in himself, that appreciation of pleasure and beauty, at that moment—well then, how could I lift myself out of my fear and grief? How could I be present, right now?

RCC: As you have just turned 60, what is your relationship to aging? How does it inform your poetry?

MD: Although many of the most vital, intriguing, and alive people I know are in their 60s or quite a ways beyond them, I’m afraid it’s still hard to shake the legacies of one’s culture. I grew up in an America in which 60 was the threshold, the number at which you suddenly became old.

Recently my partner Alex and I were both offered senior discounts at a marine life museum in Florida. I winced, but laughed, since I’ve had this experience before. But it was Alex’s first time, and he was (as he seldom is) speechless for a moment, and then sailed on as if nothing had happened. Only days later the shock of confronting being seen as a “senior” came to the fore. They were counting 50 as senior, a position I think you can only accept if you’re in a hurry to get your life over with and be done with it. My dear Alex is youthful, alive to the core, and a handsome and sexy 50 indeed, but the word—“senior”—was suddenly hung around his neck, and he had to negotiate with it.

I was gloomy about turning 60. I began to have those conversations in my head in which one wonders how much good time is left, how many books can I write, how many things can I accomplish. Is the person I am now the one I’m going to be till the end? Is this it? I took to my bed.

But that evening, in the country, our neighbors came over for wine and cheese, and there was a warm and cheering spirit in the house. At the end of the party, Alex and I and two friends drove out to a remote stretch of beach to kindle and release a present Alex had gotten for me: five sky lanterns, or fire balloons, made of paper, bamboo and wax. Dangerous, but so beautiful. You light them at the bottom, and the heat of the flame fills the balloon with hot gas, and they swell to life and tug at your hands like living things and go soaring up into the night. There was one for each decade of my life thus far—each with a different color and trajectory, seemingly even a different spirit. As we lit each one, I couldn’t imagine how it would swell and rise up and sail away; my gloom was banished by curiosity.

And that’s how I’ve felt about 60 ever since: interested.

RCC: Where do you imagine yourself at 70? What is your image of yourself then?

MD: Oh gosh. I think I will be lighter in my body. I think my blue eyes, like my friend William Merwin’s, will grow paler. My beautiful 3-year-old Golden retriever, who is my shadow and a deep well of feeling, will be 13 (spirit willing), and I hope he and I can be very present in our moment, in our age. Which is, of course, an endlessly shifting thing. Every day I am 12, and 24, and 60, and I doubt that’s going to change.

KPE: Your poetry is such a celebration of attention. In Buddhism, there is a word—smriti—that sometimes is translated as “mindfulness” and sometimes as remembering. Do you have a practice that supports your remembering of the value of attention?

MD: Poetry is the one practice I have never been able to walk away from. Writing is a way to return, to enter more deeply into the moment, to investigate its dimensions, to seek connections.

Oddly, something like this is also true in reading poetry. One must slow down, quit trying to get anywhere, and dwell in the words, allowing them to resonate, becoming open to every suggestion. Even when I give a poetry reading, which is a communal occasion, a much more social version of what readers do when they’re alone with a poem, I want to bring the listeners into a focused moment of attention, to stand together an hour, and, I hope, mutually acknowledge something about what it is to be here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.