When people ask me this question, they often seem a little embarrassed, for fear that it’s impolite or too obvious, but it’s well worth asking. After all, the end of suffering and the path to its end might be noble, but what’s noble about suffering and the craving that causes it? If anything, by attributing all suffering to craving, the truths seem to deny the possibility of noble suffering entirely. And what does it mean for a truth to be “noble” anyway?

A good place to start is with the Pali term for noble truth: ariya-sacca. This is a compound of two words: ariya (noble) and sacca (truth). The first word in any Pali compound, because it’s stripped of its case ending, can function in many ways. This is one of the reasons that people fluent in the language liked to use compounds: they can contain many layers of meaning that reward the person who tries to dig them out. Ancient commentators specialized in the game of digging out these layers, and ariya-sacca is one of the compounds in which they liked to dig. Among the meanings they found in the word ariya is that the truths are ennobling because they bring ordinary people to a noble attainment, a happiness that, because it’s unconditioned, is reliable and blameless. The truths are also of the nobles, in that noble—i.e., awakened—people have proven to themselves that these truths are true, and that they’re the most important truths to teach to others. The commentators who dug out these meanings didn’t see this sort of analysis as denying the fact that the truths themselves were noble. They simply saw it as adding resonance to the idea of their nobility.

Related: Hang On to Your Ego

For instance, even though the truths are true for noble people, they’re not true only for noble people. They’re classed as right view, part of the path that will take you from your not-yet-noble condition and lead you to a noble attainment. In other words, they’re specifically for people who aren’t yet fully awakened. They’re part of the raft that takes you across the river. Once you’re on the other side, you no longer need the raft. From that point on, the path of those who are fully awakened, like that of birds through space, can’t be traced (Dhammapada 92–93). As the Buddha said, what he learned in the course of his awakening was plentiful like the leaves in the forest; what he taught—the four noble truths—is only a handful of leaves (Samyutta Nikaya 56:31).

And the Buddha didn’t save these truths only for those who are on the verge of awakening. Once, when quizzed by a newcomer to the dhamma named Gandhabhaka, he taught the origination and cessation of suffering by using examples from Gandhabhaka’s daily life: Why did he suffer over the death or imprisonment of some people and not of others? Gandhabhaka immediately grasped the basic principle—that all suffering comes from desire—and proceeded to apply those examples to understand the anxiety he felt over his son’s safety (Samyutta Nikaya 42:11). The text doesn’t say that Gandhabhaka gained awakening, but he did see—at least to some extent—how the noble truths are true. If he had taken these truths as a guide to his life, he would have found that they’re ennobling as well.

But what makes the truths themselves noble? Among the various meanings of the word “noble,” my dictionary lists “preeminent,” “highly virtuous,” and “deserving respect.” The noble truths are noble in all three of these senses.

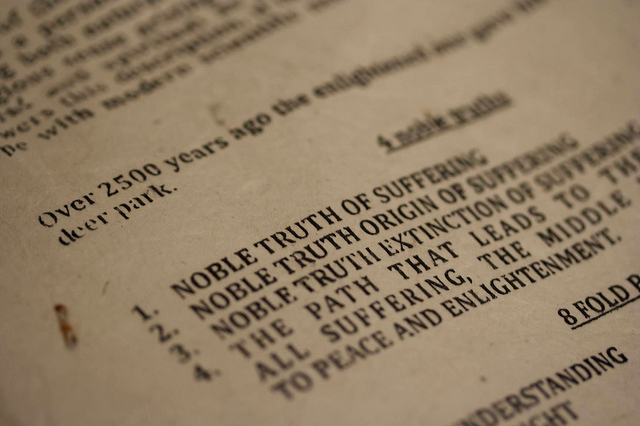

The first sense—preeminence—relates to that handful of leaves. Of all the things the Buddha learned in his awakening, the only lessons that would be beneficial and worth teaching in leading others to awakening were contained in these four truths. As Sariputta once said, all skillful dhammas fall under the four noble truths in the same way that the footprints of all land animals can fit into the footprint of the elephant (Majjhima Nikaya 28). These truths not only provide the framework for understanding everything else that is skillful, but also give directions for how to deal skillfully with whatever arises in experience. Suffering is to be comprehended, its cause is to be abandoned, its cessation is to be realized, and the path to its cessation is to be developed. In this way, the four noble truths is the Buddha’s most overarching teaching—the teaching that puts every experience in its place and tells you the most skillful way to shape your experiences into a path.

This is what the Buddha meant when he stated that he taught suffering and the end of suffering. He did, of course, in his many years of teaching, touch on other topics as well, but he always did so within the overarching framework of how those topics related to an understanding of suffering and its end. Even when he dealt with such far-ranging topics as how to make a marriage work or how to be reborn as a deva or naga, he treated them under the framework of karma, the principle underlying the fact that our actions can either cause suffering or end it. In other words, he was illustrating the principles of right view and showing both how far those principles extend and how useful they can be. If he was asked to take a position on a topic that would get in the way of gaining right view—as when he was asked to take a stand on whether a fully awakened being does or does not exist after death (Samyutta Nikaya 22:86)—he’d refuse to answer on the grounds that doing so lay outside the range of what he taught. For him, any questions that didn’t fall under these truths were a waste of time.

Related: The Buddha’s Original Teachings on Mindfulness

The noble truths are also noble in the second sense of the word: highly virtuous. This is because the act of seeing yourself in terms of these truths is a noble act. Take the first two truths as an example. The first isn’t just “suffering”; it’s the truth that suffering boils down to clinging to the five aggregates (form, feeling, perception, fabrications, and consciousness) around which we define our sense of who we are. Seeing your sense of self as inherently stressful provides some distance from it. Instead of simply following the dictates of what you think you are, you can step back from those dictates and see how they can be harmful. In this way, you begin to comprehend them, and in gaining this objectivity, you’re in a better position to act in less selfish ways. The willingness to view your sense of self in line with the first noble truth is a virtuous act in and of itself.

The same point holds for the second noble truth. It’s not just “craving.” It’s the truth that craving is the cause of suffering. To view your cravings in this way gives you some space and puts you in a position where, once you see the stress and suffering they cause, it’s easier to drop them.

Finally, the noble truths are noble in the sense that they deserve respect. This, too, relates to that handful of leaves. Of all the amazing things the Buddha could have reported from his awakening, this is what he chose to focus on: what exactly suffering is, how it’s caused, and how to put an end to it. This indicates that these truths deserve to be placed before all others.

All too often, the world tells us to ignore the suffering entailed in our clinging and caused by our craving, to regard these things as trivial and irrelevant. Our greed, aversion, and delusion are all too happy to ignore these truths in pursuit of their own agendas, the truths that hold more value for them. They prefer that craving be given free rein.

The four noble truths, however, focus our attention right at the suffering we’re causing ourselves and others, and highlight that suffering as the paramount problem in our lives. They force us to make a choice: Which are we going to respect more—our cravings or the truths of how suffering arises and how it can be brought to an end?

[This story was first published in 2013]

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.