In 2015, Haemin Sunim founded the School for Broken Hearts to offer spiritual and psychological counseling to those in need of guidance. Five years later, after coming under public attack for his secular lifestyle, he found himself in need of healing. “I was the founder of the School for Broken Hearts, yet I found my own heart in desperate need of healing,” he told Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, and meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg.

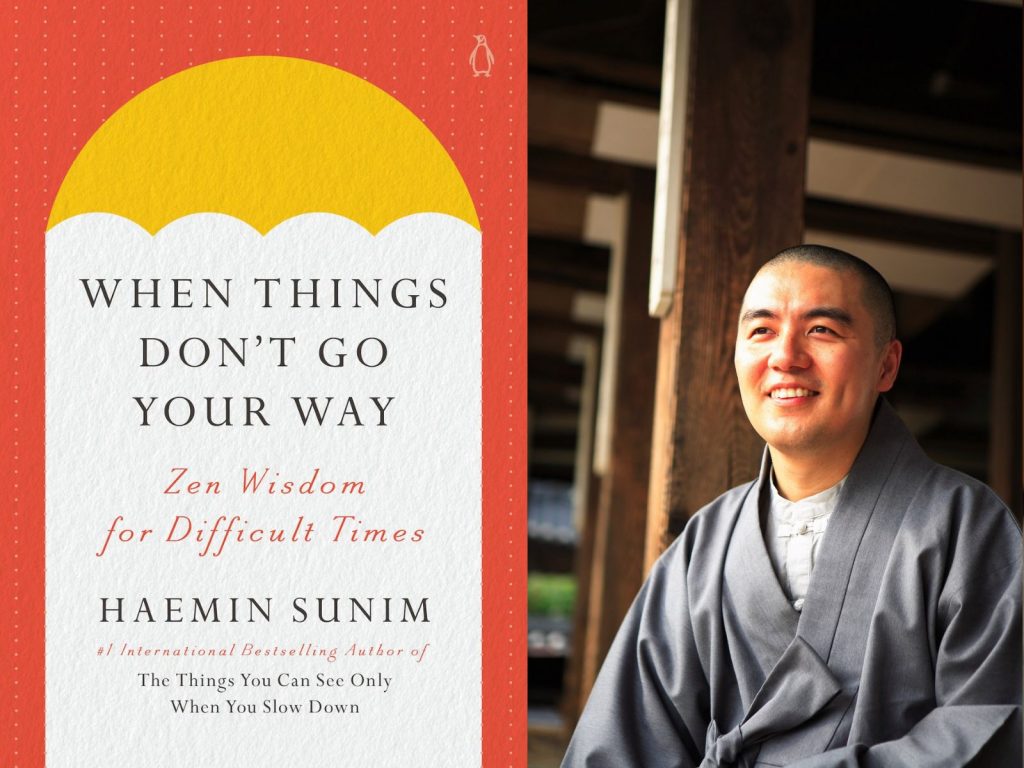

His new book, When Things Don’t Go Your Way: Zen Wisdom for Difficult Times, draws from his experience counseling others and working through his own emotions to offer a guide to transforming life’s unexpected challenges into opportunities for awakening. In a recent episode of Life As It Is, Shaheen and Salzberg spoke with Haemin to talk about the importance of learning to welcome unpleasant experiences, how giving up can actually open us to new possibilities, and how we can find happiness when we stop looking for it. Read an excerpt from their conversation below, then listen to the full episode.

James Shaheen (JS): Much of the book focuses on learning to sit with difficult emotions, and you share that one of the most challenging emotions for you personally was the fear of abandonment. How have you learned to work with this fear?

Haemin Sunim (HS): This has been a learning opportunity for me. I’ve tried to understand what my shadow is. What is it that I was not aware of or that I was too scared to confront? As I was trying to heal my heart, I saw a lot of difficult, hardened emotions within my body. It wasn’t enough for me to say that all the things that I see and feel are illusory and don’t have their own inherent existence. All the training and cultivation that I did helped. But at the same time, it was also equally real that in my body, there was a lot of traumatic energy that had to be released. I had to honor those emotions.

In the process of honoring the emotions, I started hiking a lot and talking to my trusted friends. I also started journaling, and I asked myself, “What am I afraid of?” In the beginning, my fear was, “Can I continue to support all the people who have been dependent on me for their own livelihood, my parents and my godsons, my assistants and their families, and all the teachers at the School for Broken Hearts?”

And then I asked another deeper question, “What am I really afraid of?” I came across this fear of abandonment deeply rooted in me, and then I realized that this fear was rooted in a much deeper traumatic experience. I saw that this could be an opportunity for me to take a look at that experience and really understand what it was all about.

Sharon Salzberg (SS): At the start of the book, you pose the question of why we’re so unhappy. So why do you think we’re so unhappy?

HS: We’re unhappy because we are looking for something else. We cannot accept life as it is. Instead, we are constantly chasing for something else, or we are resisting whatever comes into our way. These tendencies of either looking out to get something that we don’t have or resisting what is coming our way are the very cause of our unhappiness.

Ultimately, true acceptance is when our mind does neither—that is, when we aren’t looking for something else or resisting what is coming our way. In this moment of pause, in this moment of acceptance, we can let everything be as it is and find no self in the midst of any of this. Thereby, you feel completely free, which is your natural state. That’s where you want to arrive at.

SS: Would you describe that pause as the way to break the cycle and learn to practice acceptance?

HS: Yes, absolutely. When you pause, it also means that you step into the present moment. When we are not pausing, often we’re caught in thoughts, so we’re living in anticipation of something in the future or thinking about what happened in the past. We’re not actually seeing things as they are.

If you truly can see things as they are, everything that is appearing in front of your eyes spontaneously, magically appears without you doing anything about it. But at the same time, it constantly appears and disappears and appears and disappears. Whatever the thoughts, whatever the trouble you have, it’s no longer here. It’s just gone. It’s insubstantial. Seeing life clearly as it is instantly frees you.

JS: It can be easy to get caught up in superficial notions of happiness, where we think meeting a certain goal or achievement will bring us ultimate happiness. But it never lasts. Instead, you suggest that when our mind stops trying to find happiness elsewhere and relaxes in the present moment, we often experience what we have been searching for. Can you say more about this paradox? How can we find happiness by no longer looking for it?

HS: This was also the case for my spiritual experience. For a long time, I thought that there is such a thing as enlightenment and such a thing as the goal. Because of your incredible, immense effort, you will be able to arrive at the final destination. In Zen traditions, we talk about buddhanature as not something that you try to gain—it is something that you already have in front of you. The very act of not pursuing it allows you to awaken to your buddhanature.

All the way up until the very last moment, I guess I didn’t have enough faith that I already had buddhanature. Somehow I felt like I had to strive to get it as though it were some kind of objective goal, as though it were something separate from the reality in front of me.

What I’m trying to say is that we can relax into what is here right now, because ultimately, whether you achieve something spectacular and then feel happy or you just feel happy because you’re listening to your favorite music, the quality of your mind is the same. You are relaxed, and you are not pursuing anything else. If you can get to that same mindset, that’s what you are after.

This excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.