On September 25th, the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles will launch an interactive project that expands and reimagines what a monument can be. Led by USC Ito Center Director Duncan Ryuken Williams and Project Creative Director Sunyoung Lee, the Irei: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration aims to address the erasure of Japanese American incarceration in the US. At the heart of the Irei Monument is the first comprehensive and accurate list of over 125,000 names of every person of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II. Now, the list will be shared with the public through three distinct, interlinking elements: a sacred book of names as monument (慰霊帳 Ireichō), an online archive as monument (慰霊蔵 Ireizō), and light sculptures as monument (慰霊碑 Ireihi).

The Irei Monument project draws inspiration from the history and traditions of monuments built by Buddhist priests and incarcerated individuals in internment camps, such as the Manzanar Ireito monument (Consoling Spirits Tower) in Inyo County, California, and the Rohwer Ireihi monument in Desha County, Arkansas. “The Ireito monument is always in my mind as a reminder of this history and a Buddhist way of understanding memory,” Williams told Tricycle. “It was not just for remembering, but also for repairing. The monument was just as much for consoling those who have gone before as it was for those who remain. It’s through that spirit that we’re building these new monuments in the 21st century.”

Following an installation ceremony with community members on the 24th, the Ireichō will open to the general public at the JANM on the 25th. The Ireizō—an interactive, searchable archive—will also become available online on the 25th. Hosted by the USC Shinso Ito Center in partnership with Densho, a Japanese American educational resource that specializes in digital archives, the Ireizō will provide a digital archive of all those listed in the book of names, as well as additional research materials about the lives of the incarcerees. Further down the line, in 2024 and 2025, the Ireihi light sculptures will be installed at various sites of incarceration. These dynamic light displays will project the names of all those who experienced wartime incarceration onto monumental towers.

Based on the Buddhist doctrine of impermanence, the interlinking aspects of the monument are intended to be interactive and shifting. “Even monuments, memory, remembrance, and repair work are dynamic and changing,” Williams said. “If we think of monuments in this way—that they are, in fact, meant to be shifting and not permanent—we can have a different conception of what a monument is.”

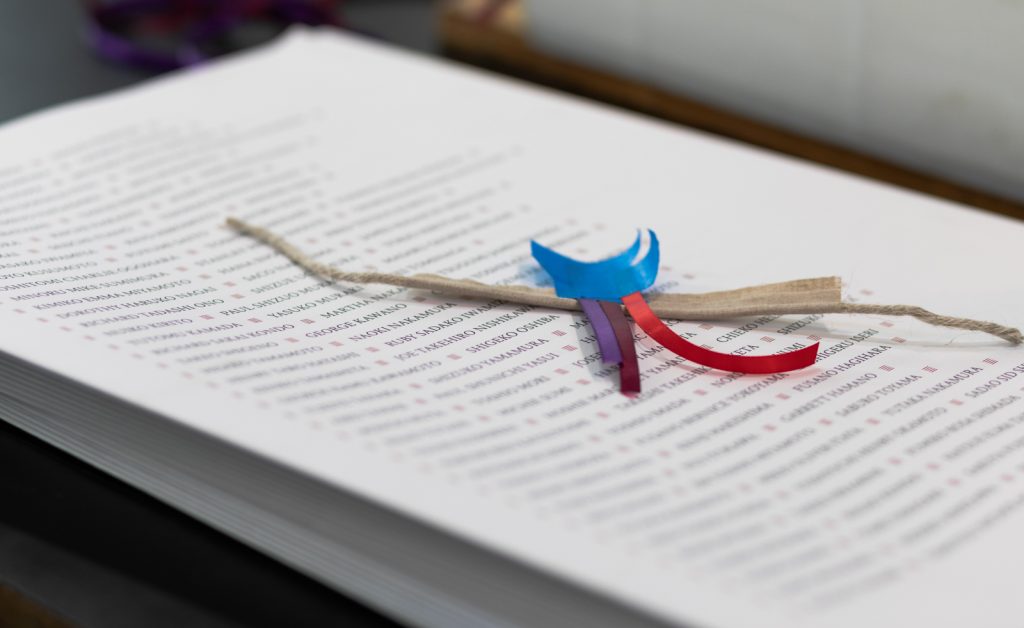

On launch day, the public will be among the first to view and acknowledge individual names in the Ireichō. The large book of names aims to not only memorialize the past but repair the fractures caused by America’s racial karma. Over 125,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated in the US Army, Department of Justice, Wartime Civil Control Administration, and War Relocation Authority camps. “Incarceration was about excising a whole community from America and seeing them as a threat to security. Whether they were a citizen, a baby, or a grandmother, it didn’t matter,” Williams said. “One effort of trying to repair this history is to give people back their personhood by naming them.” The Ireichō is sequenced from the oldest person to the youngest, and embedded into the very materiality of the book are ceramic pieces made from clay that contains soil from 75 former incarceration sites. Over the course of a year-long installation, visitors will be asked to interact with the monument by leaving a permanent mark on it using a special Japanese hanko (stamp) as a way to honor those incarcerated. By leaving a mark for each name, visitors will change the nature of the monument, and in turn, their own experience of the monument will be changed.

“The Ireichō is reflective of both a static past—which is usually how history is seen—but also this Buddhist sense of seeing the past as something that continues on. Past karma is dealt with today,” Duncan said. “The past is interlinked with the present, different communities are interlinked with other communities, and the racial karma of America can only be resolved if we do some of that repair and healing work in conversation with the past.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.