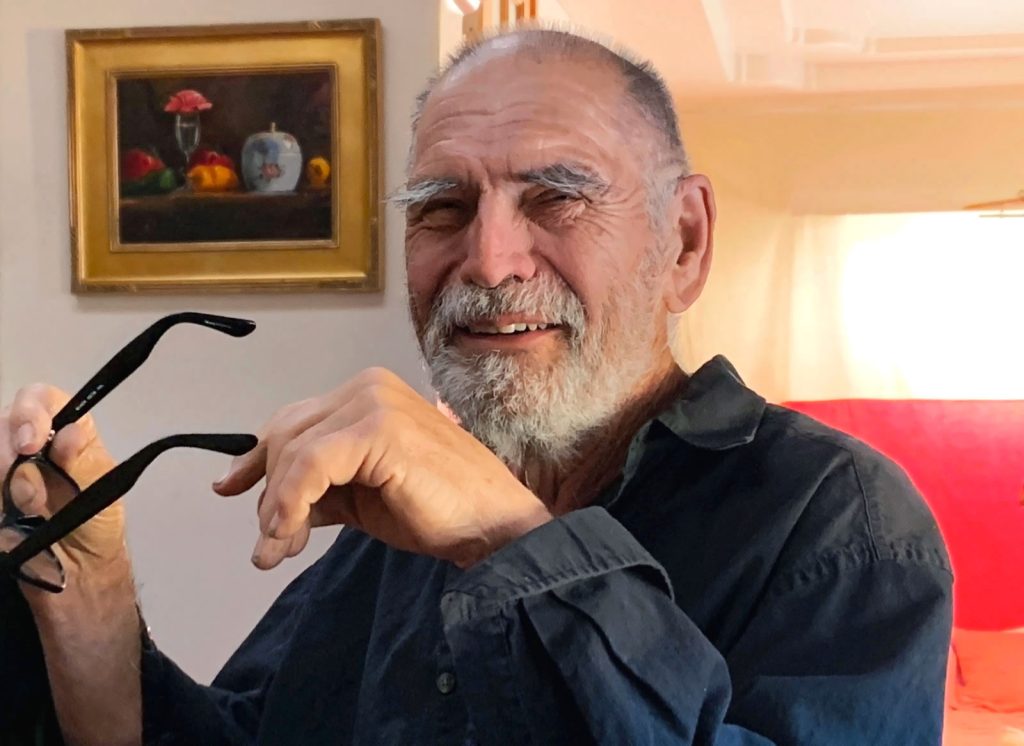

Roshi Alfred Jitsudo Ancheta, a native New Mexican who became one of America’s first Hispanic Zen teachers, died at his home in Albuquerque’s North Valley on Saturday, May 9, following a long illness. He was 76.

Ancheta was one of 12 dharma successors of Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi Roshi. He went on to form the White Plum Asanga following Maezumi’s passing in 1995. He was also a dharma successor of Tetsugen Bernie Glassman in the Zen Peacemaker Order.

Ancheta paired his devotion to Zen practice with a deep commitment to promoting peace, social justice, and interfaith understanding. In his later years he also became a skilled woodblock printmaker, blending Buddhist, Catholic and traditional New Mexican motifs in his work.

Ancheta was born in Embudo, New Mexico, a village along the banks of the Rio Grande on the road to Taos. He spent his early years there before the family moved to Long Beach, California, but he returned to the area each summer to stay with his maternal grandparents.

Ancheta’s heritage was an important touchstone in his teaching and art practice. Family lore had it that Ancheta’s mother was descended from Juan de Oñate, who led the earliest Spanish settlement in the region in 1598. His father hailed from Silver City, in the southwestern part of the state. According to the family history, an ancestor had come to the territory from Mexico in 1856.

Ancheta’s path to Buddhism was a circuitous one. He enlisted in the Army in the 1960s, serving as a medic during a tour of duty in Europe. Later he studied at Long Beach Junior College and California State University, Fullerton, where he first learned about Buddhism in a religion course.

“It intrigued me,” he recalled years later. “What I was trying to do was understand myself: ‘Who am I? What is the meaning of all this?’”A friend eventually steered him to Maezumi’s Zen Center of Los Angeles (ZCLA), telling him, “There’s a real Zen teacher there.”

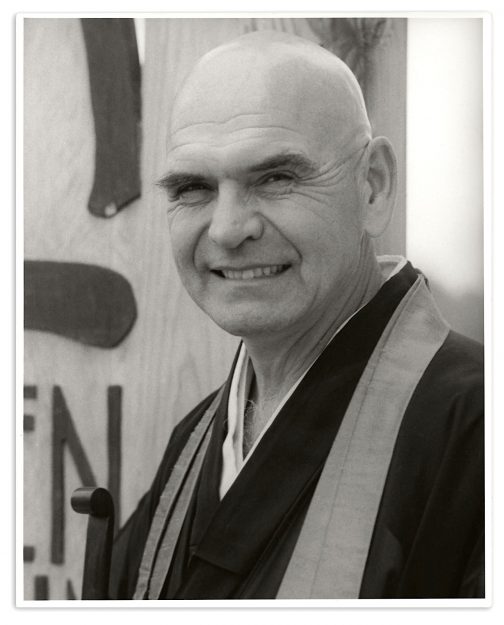

Maezumi, a Japanese Soto Zen monk who had come to the US to serve at Zenshuji Temple, the US Soto Zen headquarters, founded ZCLA in 1967. It would become the training ground for many influential American-born Zen teachers, including Glassman (Maezumi’s first dharma successor), John Daido Loori, Charlotte Joko Beck, Jan Chozen Bays, and Genpo Dennis Merzel, a schoolmate of Ancheta’s.

Ancheta’s first encounter with Maezumi, whose dharma name, Taizan, means “Great Mountain,” was memorable: “When I first saw him, I just got this wave of, ‘This is a mountain.’ It just stopped me in my tracks.”

Ancheta soon became a student at ZCLA, but in 1972, he moved to rural British Columbia with the dream of creating an off-the-grid Zen community, commuting to L.A. for 10 years to practice with his teacher. He took formal vows as a monk when he returned to California in 1982.

Maezumi soon dispatched him to a remote site high in the San Jacinto Mountains, where, as the resident monk, he helped in the construction of Zen Mountain Center (now Yokoji-Zen Mountain Center), ZCLA’s rural retreat. He came to serve as administrator and vice abbot, while reaching out to work with the homeless, at-risk youth, and HIV/AIDS patients and their caregivers. He received dharma transmission from Maezumi Roshi in 1994, with authorization to teach.

In 1995 Ancheta and some students bought a two-story Victorian-era house in downtown Albuquerque that would become home to Hidden Mountain Zen Center. In his teaching career he recognized seven dharma successors in New Mexico, Colorado, and Texas.

Thanks to his active interest in promoting interfaith connections, Ancheta served on the board of the Center for Action and Contemplation, an organization founded by Fr. Richard Rohr, a Franciscan priest. He also taught meditation at the Penitentiary of New Mexico in Santa Fe, led homeless retreats and took part in two Zen Peacemakers interfaith retreats at Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland. He was a co-founder of the Center for the Promotion of Peace in Albuquerque.

In later years, Ancheta devotedly supported the work of his wife, Diana Stetson, a noted artist and calligrapher, and launched an art practice of his own, creating acclaimed woodblock prints that found their way into art collections.

He is survived by Stetson, his wife of 25 years; his daughter, Serena Grace Ancheta Frisina; and stepson Ezra Elm Buller.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.