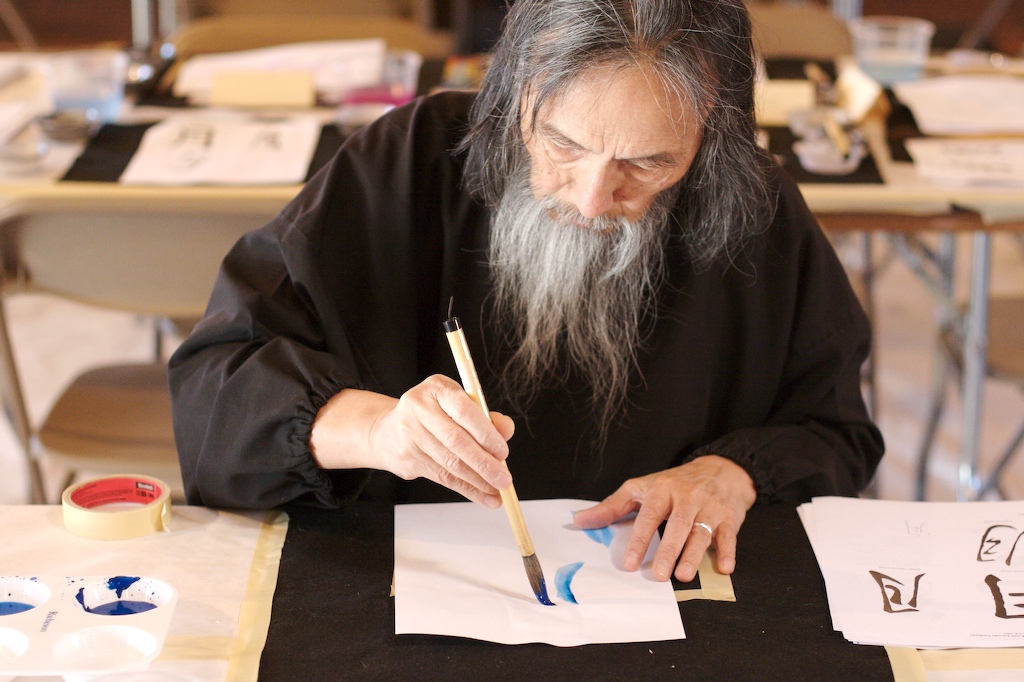

Renowned painter and calligrapher Kazuaki Tanahashi first turned to calligraphy because of his bad handwriting. “At that time, in order to apply for a job, you needed to have a good hand because people would judge your personality through your handwriting,” he told Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, on a recent episode of Tricycle Talks. Tanahashi enrolled in a penmanship course to increase his chances of getting a job, but he quickly realized that calligraphy was a much deeper art form. Immersing himself in the masterpieces of East Asian calligraphy, he set out to become an artist.

As a young artist, Tanahashi began exploring different philosophies and religions in search of inspiration. First, he turned to existentialism, but he soon found that it wasn’t for him since “to be a good existentialist, you have to be either deeply in despair or bored.” As Tanahashi was neither, he kept on searching. By chance, he came across the poems and essays of Soto Zen founder Eihei Dogen and instantly fell in love with them. “They were so difficult, and I didn’t fully understand them,” he reflects, “but I suspected something profound in them.”

When he met Zen teacher Soichi Nakamura in 1960, Tanahashi asked him if he would translate Dogen’s Shobogenzo from medieval Japanese into modern Japanese to make the text more legible to a contemporary audience. The two of them embarked on a decade-long project of completing the first complete modern Japanese translation of Shobogenzo, which they published in four volumes in the late 1970s. Tanahashi went on to translate Dogen’s writings into English as well, and in 2011 Shambhala Publications published his 1,280-page translation, Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen’s Shobo Genzo.

During this time, Tanahashi also continued his work as a calligrapher, and he became a pioneer of one-stroke painting, or the practice of creating landscapes with a single brush stroke. “Each brush stroke is essential,” he told Tricycle. “In a way, each stroke represents the state of your mind, your body, and your life.” For this reason, he believes that one-stroke painting requires the artist to be fearless.

Tanahashi carries this spirit of fearlessness into his peacework and environmental activism. Growing up in Japan during World War II, he was raised to oppose war and violence—his father was a staff officer in the Japanese army who had trained closely with Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido, and who had advocated strongly with Ueshiba against Japan’s entrance into the war. After the war, Tanahashi’s family moved to the countryside near Ueshiba’s farm, and Tanahashi studied with him clandestinely in the nation’s only aikido class at the time. Aikido’s principles of nonviolence and love fostered in Tanahashi a profound pacifism. “It’s nondual: there is no enemy,” he reflects. “Your enemy is a friend you need to protect.”

Training in aikido shaped the direction of Tanahashi’s activist career, and over the years, he has founded a number of organizations that aim to alleviate suffering and promote peace: he was the founding director of A World Without Armies: Practical Steps Toward a World Without War, the founding secretary of Plutonium Free Future, and a founding chair of Inochi, an environmental organization working to restore the Amazon rainforest.

“Each brush stroke is essential. In a way, each stroke represents the state of your mind, your body, and your life.”

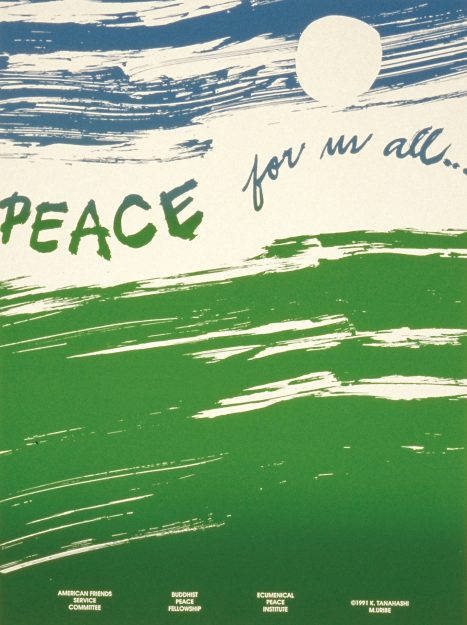

Through his calligraphy, Tanahashi has worked both to reckon with the atrocities of war and to advocate for a vision of peace, and his paintings have graced the walls of sites as diverse as the War Memorial at the United Nations Plaza in San Francisco, the Deir Mar Musa el-Habashi monastery in Damascus, the Remembering Nanjing Tragedy Conference, and Los Alamos National Laboratory. Often, he has collaborated with local artists and peaceworkers, creating large-scale ensos, or Zen circles, in public performances. To create Circle of All Nations, for instance, Tanahashi guided seven artists wielding a 150-pound brush as they moved around a twenty-foot-diameter circle while drummers and martial artists from around the world performed together.

In each of these projects, Tanahashi and his fellow artists have set out on what he describes as “Don Quixote–like” missions, attempting what may seem impossible—like trying to reverse the nuclear arms race, stop the Gulf War, and halt Japan’s development of plutonium-based nuclear energy. He believes that his background as an artist is what helps him undertake such radical tasks. “Art can help us imagine something different from our current situation,” he told Tricycle. “Imagination is artwork. As artists and poets, we can create things that are seemingly impossible.”

Now 90 years old, Tanahashi has also come to appreciate how artwork and imagination can support and guide people as they are facing illness and death. In collaboration with a group of hospice workers and clinicians, he recently released a short film called “Can We Appreciate Death?” In the film, he states, “If we are given three months or three weeks, we can try to complete our life. I don’t have a terminal illness. But I plan to complete my life by the end of 2023. I’m signing all my paintings and throwing away what I don’t need.”

Now, in 2024, Tanahashi feels that he has, in fact, finished his life. “However limited and small my life might be, this was my life,” he told Tricycle. “The rest is a bonus, so maybe I can use it for serving others.”

As Tanahashi has grown older, he has come to see death as a beautiful friend. “Death is always beside us,” he says. “A partner or spouse can say, ‘You can leave. You can be with someone else.’ But death never says that. Death is always faithfully with you.” In Tanahashi’s view, relating to death as a faithful friend can help us to die with a sense of gratitude, appreciation, and love.

As a nonagenarian, Tanahashi has continued to dedicate his life to art and service. His latest book, Gardens of Awakening: A Guide to the Aesthetics, History, and Spirituality of Kyoto’s Zen Landscapes, explores the contemplative art form of Zen gardening through the lens of seven qualities of Zen aesthetics: direct, ordinary, vigorous, gleaming, pivotal, nondual, and inexhaustible. Tanahashi views these qualities as manifestations of awakening, and he believes that attending to them can help us experience the miracles inherent in each moment.

“In Dogen’s words, miracles are practiced three thousand times in the morning and eight hundred times in the evening,” he told Tricycle. “Each moment is a miracle. Of course, you can miss it. But we still experience somewhere deep in our being the miracles of each moment. These aren’t my own miracles but everyone’s miracles: the miracles of rocks and flowers and trees and streams.”

“In Dogen’s words, miracles are practiced three thousand times in the morning and eight hundred times in the evening.”

For Tanahashi, awakening to these daily miracles is an example of how Zen art can be pivotal: something seemingly unimportant can change people’s lives. “That is the greatest function [of Zen art]: to change our lives, to change our perspective, to change our culture,” he says. “That is no small matter.”

Though Gardens of Awakening was just published last month, Tanahashi has already completed the manuscript of his next book, Fresh: The Art of De-Aging and Joyful Living, and shows no signs of stopping any time soon. For Tanahashi, the secret is recognizing that we can change how we relate to every moment. “Even when we are very sick or close to death, we can feel fresh,” he told Tricycle. “Each moment, we have a choice.”

◆

Images from Painting Peace: Art in a Time of Global Crisis by Kazuaki Tanahashi © 2018 by Kazuaki Tanahashi. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.