The Sources of Buddhist Traditions is a monthly column from three of the major digital resources for Buddhist research, texts, and translation: Buddhist Digital Resource Center, The Treasury of Lives, and 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha. Focusing on stories, texts, translation, and teachers, the series will illuminate aspects of Buddhist practice, thought, and tradition.

A year before the pandemic, my aunt Somo Yangzom and I were on our way to one of the local Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Kathmandu when she turned to me and said all her friends were dying. In her eighties, she called herself one of the last ones left.

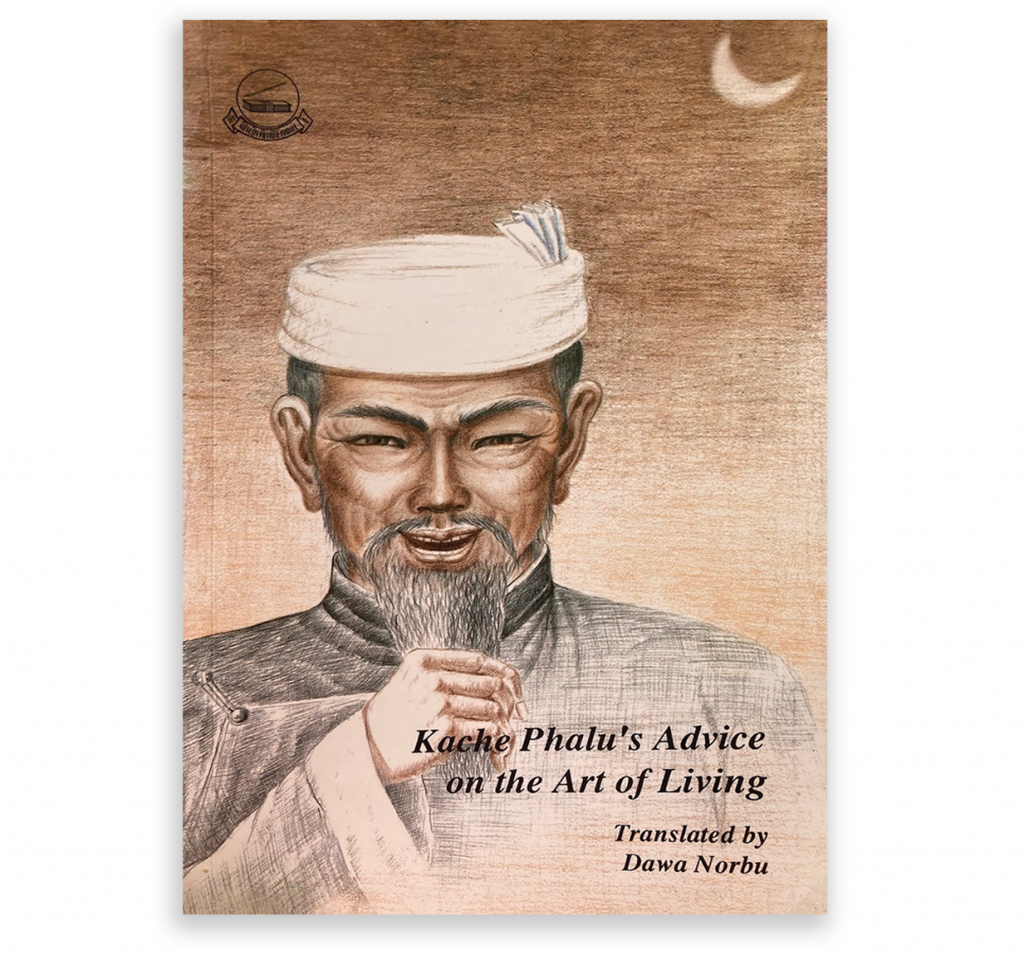

“‘They keep coming and they keep going. All who come must go in the end.’ This is Khache Phalu’s advice,” she told me, quoting Khache Phalu’s Advice on the Art of Living, a beloved classic Tibetan text.

Though she never learned to read or write and didn’t go to school, my aunt, who came from Tibet into exile in Nepal as a young woman, still managed to commit several long prayers and verses to memory, including many from Khache Phalu. With characteristic humor and insight, she deploys verses from this text at all the right conversational bends, quoting it the way she quotes her lamas and teachers.

Speaking of a local Tibetan who was known to be light-fingered, she has said, “It’s the parents. They should have taught him better, stopped him when he first started stealing. As it says in Khache Phalu:

“’If you don’t discipline your child when he steals an egg,

Then he’ll go on to steal a chicken, followed by a horse!’”

Khache Phalu is her source text, and its eponymous author one of my aunt’s teachers. He is a guru lighting the path for her, dispensing the right advice in ordinary moments of stress and distress, strife and sadness, love and laughter. He was also a lay Kashmiri Tibetan Muslim merchant.

We are used to the story of Tibet as an insular Buddhist society, but the existence and continued popularity of Khache Phalu tells a different story.

Muslim merchants from Kashmir likely first arrived in Tibet in the 14th century. The word “khache” referred to Kashmiris, but Tibetans came to use it to identify Muslims from anywhere. During the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama in the 17th century, they began to settle permanently and to intermarry with local Tibetans. The Fifth Dalai Lama, under whose rule Tibet began to emerge as a major political force in Inner Asia, gave the new Muslim minority not only his support and patronage, but even a land grant to build a mosque and a cemetery. By 1950, there were around three thousand Muslims in Lhasa, a sizable minority, and four mosques, two very close to the Jokhang Temple, Lhasa’s holy Buddhist cathedral.

Writing about 1840s Lhasa, the French missionary Abbe Huc said, “The permanent population of Lhasa consists of Tibetans, Newaris [Nepalis], Khache [Muslims] and Chinese.” Muslim communities weren’t just in Lhasa, either. They lived in Shigatse, Gyantse, Tsethang, and elsewhere on the plateau.

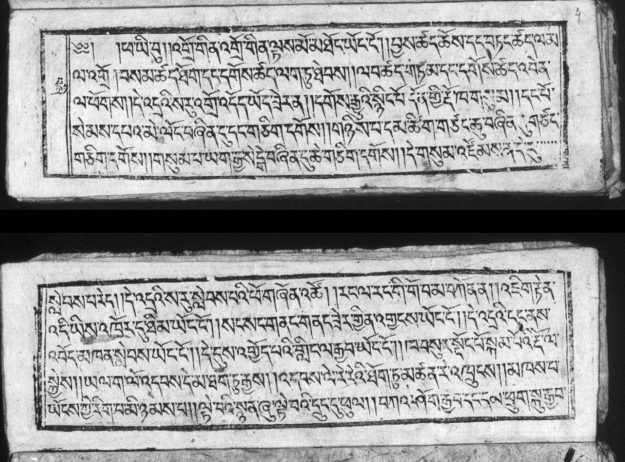

Khache Phalu’s Advice, a work of aphorisms in verse and a testament to this Tibetan Kashmiri-Muslim community, appeared sometime in the eighteenth century and became universally beloved across Tibet. For the next two hundred years, Khache Phalu’s Advice was a mainstay of Tibetan cultural education. Even if the book was not formally taught in monasteries, all Tibetans, educated or not, could quote from it. The book is still read, memorized, and most importantly, widely quoted, today. Like verses from Shakespeare in English, lines from Khache Phalu have entered the common Tibetan repertoire of sayings.

How did a Kashmiri Muslim text become a Tibetan bestseller? The simple answer is that the advice in Khache Phalu connected deeply with the Tibetan people because it commented directly on their everyday experiences. Everyone from learned monastics to self-taught businesswomen like my aunt felt that Khache Phalu had something to teach them about how to live their lives, how to conduct their relationships, and how to manage their responsibilities. Most importantly, it taught them in clear and colloquial language that people actually understood.

Using neither the high register of Sanskrit kavya poetry, with its ornate and figurative language, nor the specialized terminology of the Tibetan Buddhist canon, Khache Phalu’s advice, given in the language of the people, sounded exactly like wisdom from an intimate elder:

“Rather than having tea and chang [barley wine]

with strings attached,

it is better to eat one’s own grass

and drink one’s own water.

Rather than having meat from the hunter,

it is better to eat one’s own fleas.

Eating and sleeping

only, cows and donkeys do.

Is it good to do such things, my son?”— Translation by Dawa Norbu in Khache Phalu’s Advice on the Art of Living.

Khache Phalu belongs to the genre of Tibetan wisdom literature that has its roots in Indian wisdom literature and concerns itself more with worldly advice than with spiritual guidance, using literary conventions to connect with readers. People embraced the book as a work of literature, and accepted its Muslim features no doubt in part because of the author’s literary skill. As observed by historian David G. Atwill in his 2018 book Islamic Shangri-La, when Khache Phalu “emphasizes his monotheism or invokes Allah, the tone of the text beautifully utilizes Tibetan patterns and allusions to make whatever might possibly be perceived as ‘un-Tibetan’ into something undeniably Tibetan.” Indeed, Tibetan Muslims were and still are well known for their facility with the Tibetan language, especially for using the pure high honorific register of Lhasa locals. In 2014, at a public talk in Los Angeles, His Holiness the Dalai Lama praised Tibetan Muslims in Srinagar for their excellent, Lhasa-accented Tibetan, passed down to them by their parents and grandparents.

Of course, Khache Phalu also heavily supplemented the text with Buddhist references as well. For instance, he reminds us:

“Offer prayers of homage with body, speech, and mind.

Supplicate the precious Three Jewels, the eternal source of help.”— Translation by Beth Newman in Thupten Jinpa’s edited volume, The Tibetan Book of Everyday Wisdom: A Thousand Years of Sage Advice.

In fact, his Buddhist references were so apt that not only were there rumors that he was a Buddhist masquerading as a Muslim, but there was even a rumor that the Sixth Panchen Lama was the real author of this text.

After all, only a handful of texts are as well known and beloved among the ordinary Tibetan people. And all of them, including the Elegant Sayings of Sakya, the Treatise on Water, and the Treatise on Wood, were written by Tibetan Buddhist monks.

But it’s the mercantile flavor, with a dash of Machiavelli, that truly sets this work apart from others of its kind. For instance, a Buddhist author would never write the following lines:

“Parents should bring up their sons to acquire wealth.

Listen to an old man who has lived many years,

for old men have experienced much joy and sorrow.

When you reach the border with the iron fence,

an old man’s tactics are better than the strength of youth.

If you want to conquer your present enemies right away,

it is best to draw them in as your friends for now and wait.”— Translation by Beth Newman in Thupten Jinpa’s edited volume, The Tibetan Book of Everyday Wisdom: A Thousand Years of Sage Advice.

“Bring up your sons to acquire wealth” is the direct opposite of advice that would come from a Buddhist monk, who would suggest collecting merit instead of money. But it is advice that Tibetan parents would actually give their children. It’s little wonder that parents, and aunts, actually quote the text so frequently. “An old man’s tactics are better than the strength of youth”—yes, indeed! But the last lines, with their worldly and extremely un-Buddhist counsel toward pretense, subterfuge, and betrayal, are the ones that really give the author away.

Consider these lines:

“In summer take care of your iron plow; in winter take care of your slate roof.

Take care of your red tongue no matter what the season.

Gauge how many secrets to tell your dear friends;

friends in the morning often become enemies by nightfall.”— Translation by Beth Newman in Thupten Jinpa’s edited volume, The Tibetan Book of Everyday Wisdom: A Thousand Years of Sage Advice.

Khache Phalu knew firsthand the demands and obligations of keeping up a household, and much of his advice is explicitly useful. But he didn’t just advise on household chores and seasonal tasks; he also understood ordinary people.

Some have suggested that Khache Phalu became popular in spite of its Muslim origin—that it is essentially a Buddhist text, in spite of its Islamic undertones and overtones. In fact, Khache Phalu became popular with Tibetans not in spite of its Muslim and mercantile origin but exactly because of it. Tibetans love it to this day because it was written not by a Tibetan Buddhist monk but a Tibetan Muslim merchant and lay householder who knew the mundane world intimately.

The monk may know more about nirvana, but the merchant knows more about samsara—he lives in the very heart of it. The merchant must observe his fellow humans; his livelihood depends on how well he knows his customers and clients. As Professor Dawa Norbu, who produced the first translation of Khache Phalu in English (published by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, in 1987) pointed out, “As a merchant, Khache Phalu was strategically situated in Tibetan society. As a naturalized Tibetan, he was a participant, but as a Muslim, he was an observer.”

Khache Phalu had both the observer’s distance and the participant’s experience. He distilled both into his text.

It’s worth remembering, when we think of Tibet as a monolithic Buddhist society, that one of its best-loved texts was written by a Muslim. And that the Tibetan Buddhist culture of his day had myriad influences, as it still does today. Muslim by religion, Tibetan Buddhist by culture, and merchant by trade, Khache Phalu became an unlikely and yet perfect kalyana mitra, the wise spiritual friend guiding his audience on the right path to a good life.

As my aunt knows, Khache Phalu has a lot to teach us:

“Only a madman will change gold for brass,

Only a fool will mistake stone for turquoise.

If you don’t understand the difference

Between this life and the next,

You will waste your mundane samsaric life.

After a year or two and a hundred more,

Even your earthly body will turn to dust.

The king on his golden throne

And the beggar in the street

Die the same death

By impermanence.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.