Larung Gar, the largest Buddhist academy in the world, has long been a reluctant theater for the unceasing struggle between Tibetan spirituality and Beijing’s brutality. This embattled mountain hermitage in eastern Tibet is the subject of a New York art show currently on view at Tibet House. Essence features Tibetan artist Gyatso Chuteng, whose paintings communicate the magnificence of the sprawling religious establishment founded by the late Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok in the 1980s.

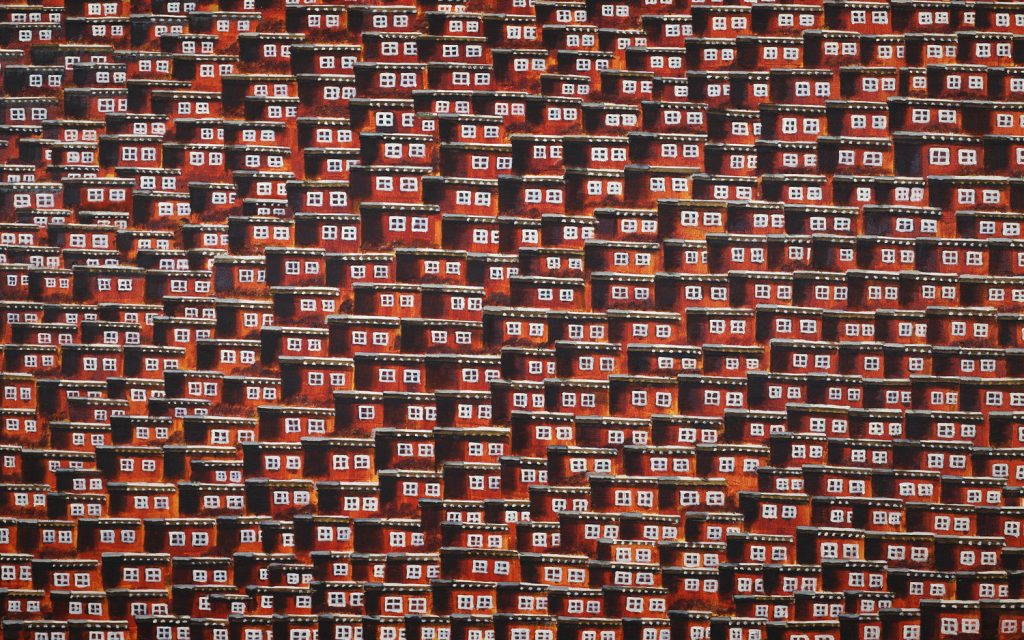

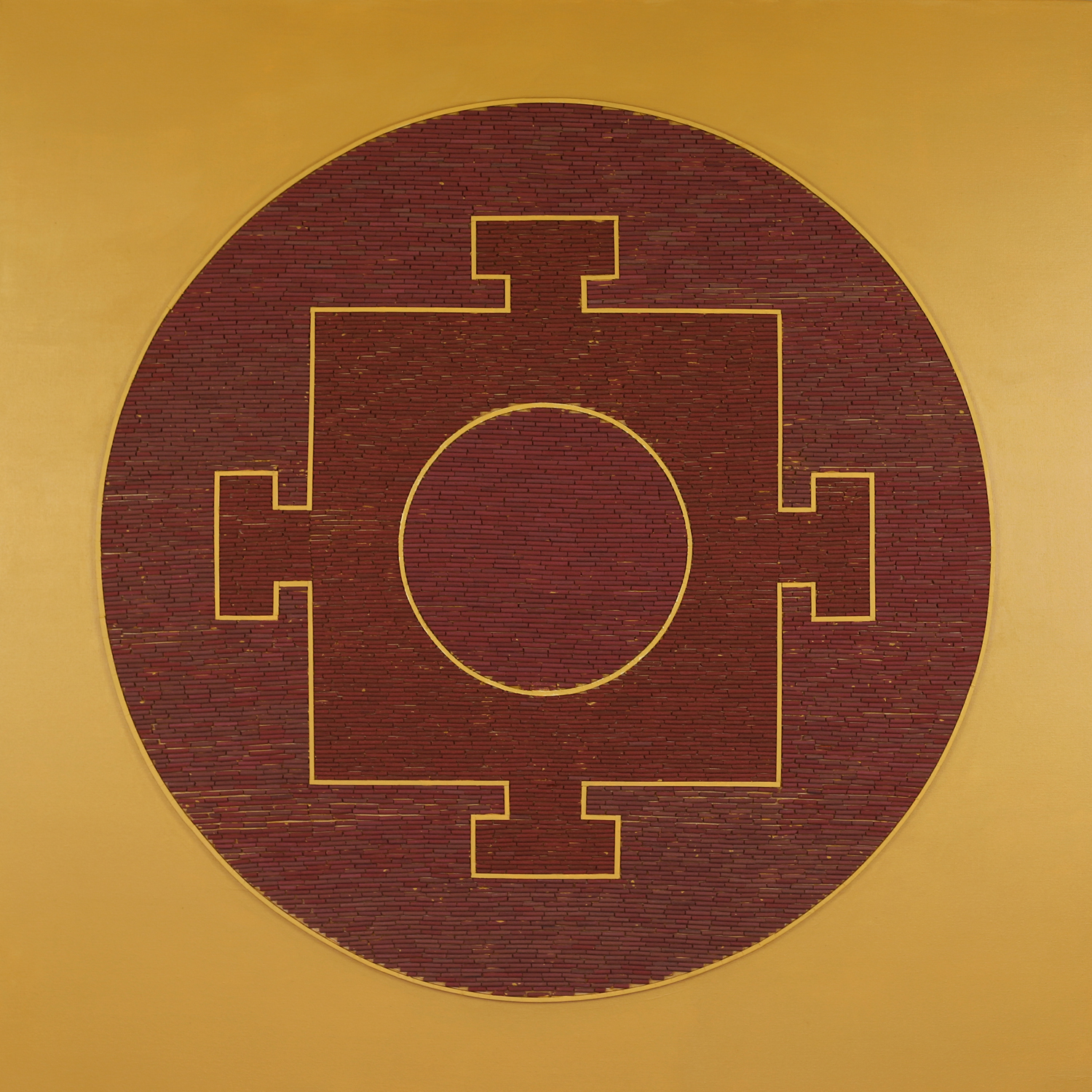

Using several thousand fragments of incense sticks, Gyatso has painstakingly produced aerial views of the thousands of mud dwellings that populate Larung Gar—each work resembling an architectural mandala.

“Finding the right material is as critical for an artist as it is for an architect or a builder,” says Gyatso, who was trained as a civil engineer in India and later as an interior architect in Berkeley, California.

“The thick maroon colors and the vertical depth of the Larung Gar . . . challenged me to explore mediums that go beyond paint or pigment . . . to find something that mirrors the subject in an original way. So when I was hit by the idea of using incense sticks, I was ecstatic. It was the perfect answer to all my questions, and it added a fourth dimension to the art—that of fragrance.”

The subtle fragrance that still lingered in the exhibit hall brought me back to the faith and devotion that animate the temples in my ancestral homeland of Tibet, where incense sticks and butter lamps smoke and flicker day and night. The medium effectively captures the faith and fragility that define this spiritual community living on the edge of survival and destruction.

Just as Gyatso began to commit to canvas the sublime beauty of Larung Gar, the establishment came under attack.

The Chinese government demolished 4,725 monastic dwellings at Larung Gar in June 2017 and expelled 4,828 monks and nuns who lived and studied there. The world saw footage of weeping monks and nuns being shoved into buses that would carry them back to their original hometowns, where they would be deprived of an opportunity to pursue religious studies.

“I had just started working on my pieces with great joy and excitement when China started destroying this peaceful community, reducing each of the humble cabins to rubble and forcing the residents to sign their expulsion documents,” Gyatso said.

Gyatso’s journey into contemporary art has been anything but straightforward. Born in a Tibetan refugee camp in Nepal and educated at an exile boarding school in India, he moved to California at the age of 27. For the next five years, he kept his nose to the grindstone, balancing full-time school and full-time work. After graduating, he worked in a San Francisco firm for a few years, and then landed a job at an elite design firm in New York.

Gyatso rented an apartment in midtown Manhattan. But each day after work, he was drawn to the chaotic streets of Queens, where a small but tight-knit community of Tibetan contemporary artists lived under the elevated 7 subway line. They painted occasionally, partied consistently, and philosophized incessantly. As Gyatso fell in with this group of barefoot artists, he began to make his own artworks. He showed his works at group exhibits such as Imago Mundi (Venice 2013) and Art for Tibet (New York 2014) alongside established artists like Pema Rinzin, Gonkar Gyatso, and Tenzing Rigdol.

A few years ago, Gyatso decided to take a leap of faith and pursue painting as a full-time career. But it was his background in architecture that originally drew him to Larung Gar’s epic scale and proportions, and the mesmerizing color and composition of this city in the sky.

“I was blown away when I first saw photos of Larung Gar. Thousands of tiny houses, densely packed, all clad in maroon and almost identical to each other … it made for a striking architectural landscape,” says Gyatso. “I at once felt the urge to capture such beauty and complexity through art and share it with the world.”

For Gyatso, the destruction of the religious establishment felt like a personal violation. While China’s routine abuse of human rights never failed to outrage him, the demolitions at Larung Gar devastated him.

Beijing’s hostility to Buddhism is no secret. But until recently Larung Gar had remained one of the extremely few monasteries in Tibet where rigorous study of the Buddhist canon was tolerated by the authorities. In the rest of Tibet, traditional academies of Buddhist learning have been systematically dismantled through decades of assault by the Chinese state. In recent years, police stations and surveillance cameras have been set up in the monasteries, where instead of classes in Buddhist philosophy and ethics, monks and nuns are forced to undergo “patriotic reeducation” programs. Monks educated in India are banned from giving religious teachings, while possessing the Dalai Lama’s photo is an imprisonable offense. In the Tibet Autonomous Region, Chinese authorities have barred schoolchildren from taking part in devotional practices during the holy month of Saga Dawa. In this sense, Larung Gar had been the exception that has come to prove the rule.

Gyatso has vowed to keep this sacred place alive in the public imagination. Over the last year, as Chinese authorities bulldozed the monastic buildings and flattened the maroon dwellings, Gyatso toiled away in his Queens apartment, meticulously rebuilding Larung Gar—if only out of incense sticks.

The completed Larung Gar series is now on view at Tibet House through July 26. Essence also features the works of Japanese artist Yasuko Ota alongside those of Gyatso Chuteng.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.