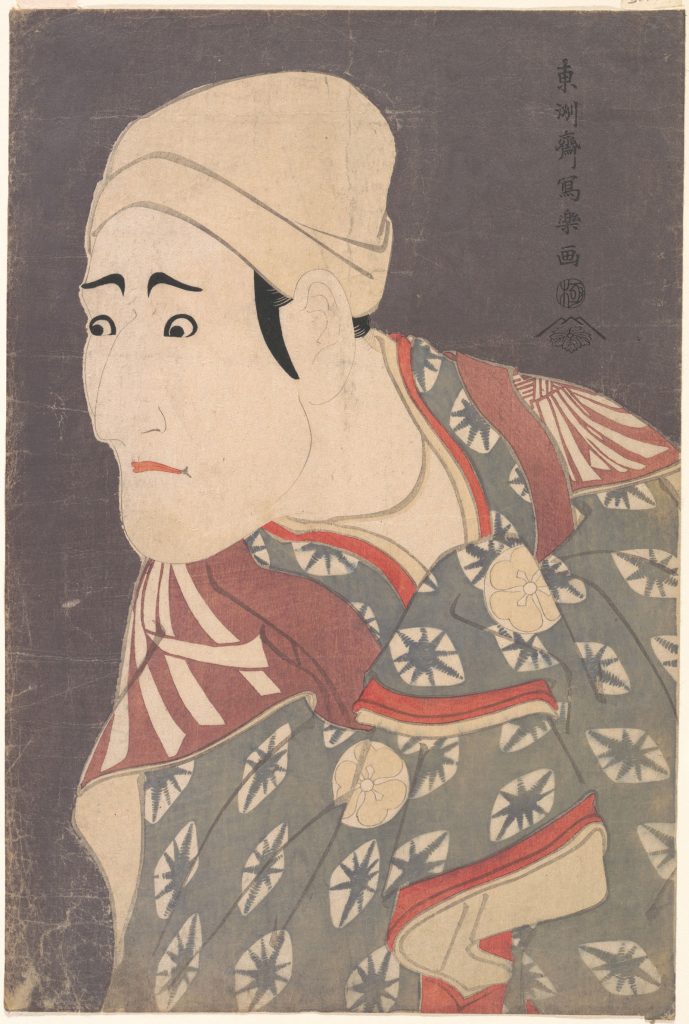

I have long had the sneaking suspicion that Buddhists are especially prone to guilt—that it lurks underneath meditation cushions and leaps out from paintings of Bodhidharma’s bushy, judgmental brows. Perhaps I’m projecting, but it seems that many Buddhists, especially converts, begin to meditate because we are hoping to find the special thing that will complete us. Even though Buddhist teachings state that we all have buddhanature, the very act of striving to uncover it can end up reinforcing the idea that we are in some way lacking. So when we don’t have the time, energy, or discipline to sit, we end up feeling guilty.

That guilt can sometimes be a helpful motivator. I, for one, have trudged to my cushion countless times out of sheer obligation, and have often risen 30 minutes later grateful for the nagging sensation that kept me on the middle path. Yet stewing in guilt can become a pointless exercise in masochism.

In any case, there is no denying guilt’s power. But how can we work with this power? Can we use guilt to help us stay committed to practice, or does laying a guilt trip on ourselves ultimately do more harm than good?

Tara Brach, who has a Ph.D. in clinical psychology and is the founding teacher of the Insight Meditation Community of Washington, DC, says that all emotions can hold intelligence—even guilt. She suggests that one way to understand guilt better may be to observe how it arises and learn to recognize its intelligence as well as its pitfalls.

“With healthy guilt, the message is that we have behaved in a way that is not aligned with our values and heart,” said Brach. “If we are listening, it can be a wake-up call. It reminds us to deepen our attention, remember what most matters to us, attune to our impact on ourselves and others, and adapt our behavior.”

In other words, guilt can offer an opportunity for course correction. For example, I have made the commitment to meditate every day, and on a recent Sunday was getting ready for bed when I realized that I had completely forgotten to practice. But before the age-old cycle of guilt could take hold, it occurred to me that nothing was stopping me from sitting right then, and that it would in fact be a much better use of my time than wallowing in self-reproach.

In fact, Brach notes, a guilt trip can really be a way of feeding our egos.

“Acting from guilt is not transformational,” Brach said. “It reinforces our identification with a deficient self. Rather than being linked to values that feel intrinsic and pure, our guilt arises from the internalized values of our caregivers and society. It comes with a judgment of personal ‘badness.’ Guilt’s ‘on button’ gets jammed, and it becomes an ongoing presence in our life.”

This can make it difficult to tease out the potentially helpful aspects of the emotion. My guilt about trying to sit every day can become wrapped up in my guilt about trying to exercise every day, which can tie into my guilt about flossing. All guilt can start to fall under the umbrella of personal badness.

“Even when our guilt is triggered by not doing something we truly value—our meditation practice—it is so layered with self-aversion that we are unable to listen to its message,” Brach said. When we rush to overcome this feeling of deficiency, by, say, meditating with repentant fervor, we tend to propagate this narrative. In these instances we become either the best or the worst meditator ever, but in the end it’s still all about us.

Is there a way out of this spiral? According to Brach, we have to pay attention to what’s under the guilt we feel over not meditating and see that it reflects our “longing to awaken our heart and awareness through our practice.” In this way, guilt can point us back to our original intention instead of the story we make up about being lazy or diligent meditators.

“When caught in guilt,” Brach says, “it is wise to pause, hold the guilt with self-compassion, and reconnect with what really matters to us.” By making room for our guilt and seeing it clearly, we can accept it without feeding into it.

For those of us steeped in guilt, this might be easier said than done. My Jewish mother needs only to hint at being sad—the corners of her mouth beginning to twist downward in a pantomime of sorrow—for me to acquiesce to her wishes. But learning to recognize the intelligence behind the desire to please my parents, and shedding the baggage associated with it, is a skill even my mom would approve of.

♦

To help us relieve the burden of unnecessary guilt and show ourselves more compassion, Brach has put together the following guided meditation.

Practice: The RAIN of Self-Compassion

By Tara Brach

As you come into stillness, take a few full breaths—a nice deep in-breath and a slow out-breath. And again, a nice deep, full in-breath, filling the chest and filling the lungs, and then a slow out-breath, feeling the sensations of the breath as you exhale.

Letting the breath resume its natural rhythm, just feel this body breathing.

Now take a few moments to scan your life. You might notice the places where you feel like you’ve turned on yourself in some way. It might be in a situation where you are in conflict with another person but feel bad about yourself—maybe you have a sense of unworthiness or guilt. Maybe you’re at war with yourself over your behavior as a parent, partner, or friend. You might be judging yourself for something to do with work or for an addictive behavior.

Where do you get into this trance of unworthiness, the trance of “not okay”?

Let your attention go to that place where you get into the trance and, for now, just let yourself get close. Feel what it is like to be living inside the belief that, in some way, you’re falling short or that you should be different. Perhaps there’s a sense of not being lovable, not okay, not respectable, or that something’s wrong.

We begin the RAIN (Recognize, Allow, Investigate, Nourish [or Non-identification]) of self-compassion by recognizing this is a trance—I’m at war with myself—recognizing the thoughts and feelings of the trance, and then just allowing them to be here, making room for what’s here right now.

The “A” of RAIN is to allow. This is how it is right now.

Then we begin to investigate with curiosity and gentleness: what is it like when I’m in this trance? You might sense what you’re believing about yourself and other people. What’s the belief right there? I should be different? I’m bad because I’m hurting others? No one could love me? I’ll always fail?

Sense what might be built in there—what kind of core belief—and, most importantly, feel your body and sense, when you’re in the trance of unworthiness, what it is like in your body. What does your throat feel like (or your chest or belly) when you’re really feeling bad about yourself?

The most important part of investigating is connecting with the embodied experience. Sense the most vulnerable part of yourself: where do you feel the worst? What does it need? Does it need to be seen in a different way? Loved? Understood? Held?

As you’re listening into that vulnerable place, you might experiment with putting your hand lightly on your heart, a very tender touch. This is the beginning of turning toward loving and toward the “N” of RAIN—nourishing.

Sense the possibility of offering what’s most needed inwardly. You might offer words of care: It’s OK, sweetheart or I’m sorry, and I love you. Thich Nhat Hanh says: Darling, I care about this suffering.

You might call on the love of a larger presence—a deity or a notion of the divine. Sense the possibility of calling on love and offering it inward.

Nourish with self-compassion, letting it be a fresh and creative exploration of what allows you to feel love flowing into your being. You might imagine light and warmth pouring in. Just the intention to offer care inwardly begins to decondition the tendency to be at war with ourselves.

The meditation becomes full when, after the steps of RAIN, we simply notice and ask ourselves: who am I when I’m not believing something is wrong?

From the teachings of the Indian master Bapuji:

My beloved child, break your heart no longer. Each time you judge yourself, you break your own heart. You stop feeding on the love which is the wellspring of your vitality. The time has come—your time to live, to celebrate and see the goodness that you are. Let no one, no thing, no idea or ideal obstruct you. If one comes, even the name of truth, forgive it for its unknowing. Do not fight. Let go and breathe into the goodness that you are.

This meditation originally appeared on Tara Brach’s website.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.