With magic, murder, and a protagonist who loves to sing, the story of the Tibetan Buddhist saint Milarepa sounds like it could be the plot of an opera—and now it is, thanks to the work of the award-winning composer Andrea Clearfield and librettists Jean-Claude van Itallie and Lois Walden.

Mila, Great Sorcerer, which debuted in January 2019 at the Prototype Festival in New York, follows the aristocrat Mila Topaga as he learns sorcery to kill his aunt and uncle, who have stolen his inheritance. As the first act ends, Milarepa’s act of vengeance ends up destroying his whole village. The second act traces his path of redemption as he seeks out the teacher Marpa, who starts Mila on the Buddhist path.

Andrea Clearfield’s dynamic score brings van Itallie and Walden’s adaptation to life, drawing influence from Tibetan music. Before composing Mila, Great Sorcerer, Clearfield, a longtime Buddhist practitioner, traveled through the Himalayas recording folk and court songs with ethnomusicologist and anthropologist Katey Blumenthal, which are now part of the University of Cambridge World Oral Literature Project. She has also written compositions for the Philadelphia Orchestra and received accolades from the New York Times and a variety of awards and fellowships.

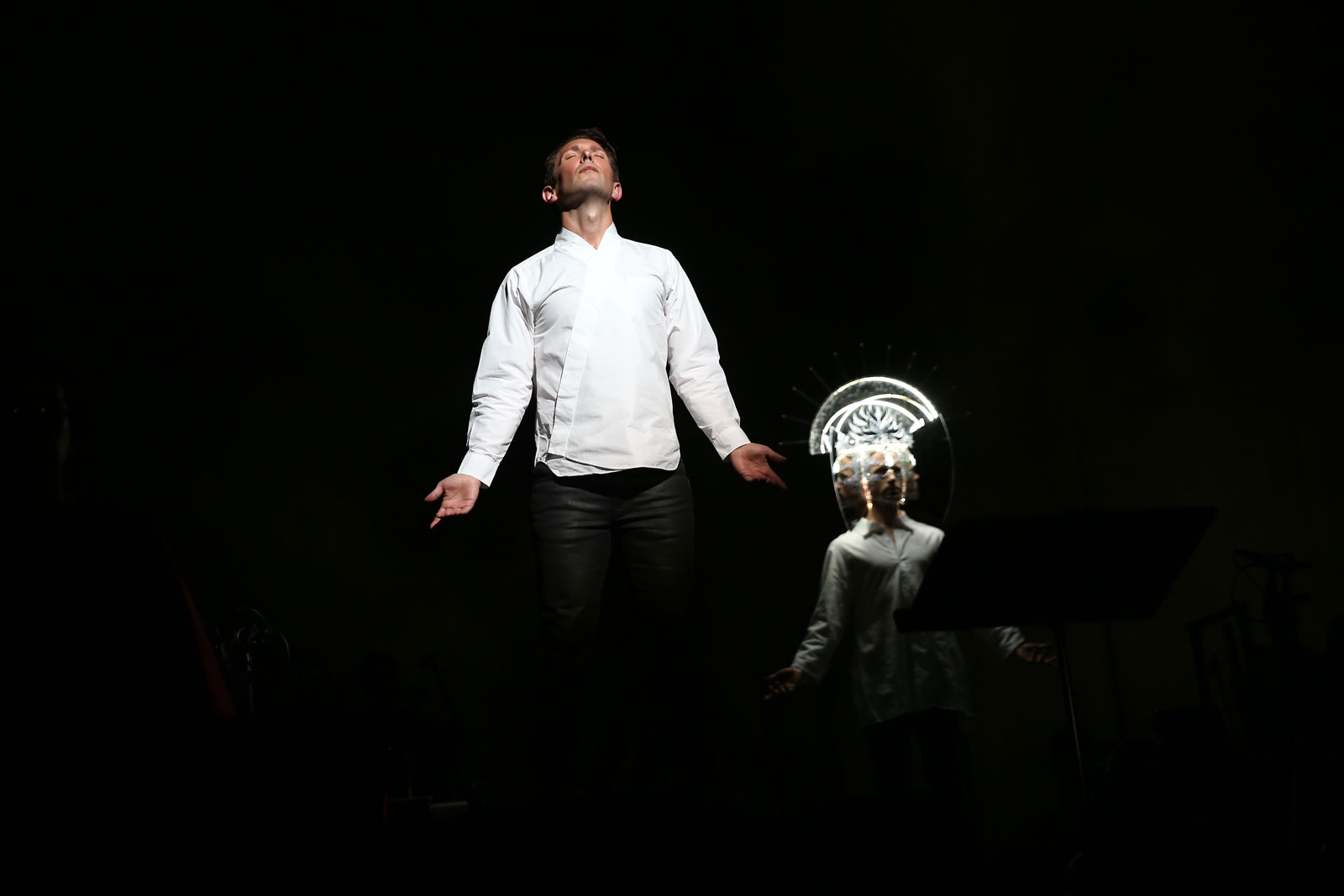

The staged reading of the opera was performed against a backdrop of animations featuring works by contemporary artist Tsering Sherpa and traditional thangkas [scroll paintings] courtesy of the Rubin Museum, and the cast was accompanied by a double choir from the New York Virtuoso Singers and an ensemble of Western and Tibetan instruments played by the chamber orchestra The Knights. The opera was commissioned by Gene Kaufman and Terry Eder, directed by Kevin Newbury, and produced by New Vision for Opera NYC.

Tricycle spoke with Clearfield about the process of composing an opera about Milarepa, her research in Nepal, and what she hopes people can learn from the great Buddhist teacher’s life story.

How did this opera come about?

In 2011, I’d just returned from researching Tibetan music in northern Nepal when I went to hear The Tibetan Book of the Dead by Jean-Claude van Itallie. I didn’t know Jean-Claude, but I was so moved by the performance that I introduced myself to him, and a very auspicious conversation ensued. I told him about my work and he asked, “What do you want to do next?” And I said, “I’ve been dreaming of writing an opera on the life of Milarepa, whose story moves me so deeply.” Jean-Claude looked at me in astonishment. He said, “I have just completed a libretto of a life of Milarepa along with novelist Lois Walden. And the commissioners are looking for a composer.”

Why were you thinking about writing an opera about Milarepa?

I had been researching and recording ritual and folk music in Lo Manthang, in Nepal’s upper Mustang region, and that the area is close to where Milarepa lived and meditated. I became familiar with his story, and it resonated with me. I’ve long believed in human transformation, and Milarepa not only teaches but also shows us through his life story that it is possible to transform and to redeem your soul. And he shows that suffering can be a portal to awakening.

Plus, he was a singer—a bard in some sense. He’s perhaps the most venerated saint and teacher, and as far as we know it, he sang his teachings. So listening was an essential part of it. We see him in the thangkas with his hand to his ear. He teaches how to listen inside to find the stillness and to see who we really are.

As a musician, listening of course is something that we develop as part of our awareness—to listen as a composer to what needs or wants to be said, to listen when we’re performing in relationship to the others, to the breath, to the phrases, to the body language. This deeper listening really drew me so strongly to Milarepa on many levels.

Can you tell us more about the research you were doing at Lo Manthang?

In 2008, the Network for New Music, a Philadelphia-based contemporary music ensemble, asked me to collaborate with a wonderful visual artist, Maureen Drdak, who gets much of her inspiration from Tibetan Buddhist iconography. When Maureen and I found out that we were going to be collaborating, she asked me if I’d like to join her on a trek she was planning to upper Mustang to do research for her artwork. And I said “yes.”

While I was there, I made a lot of recordings with permission from our friends in Lo Manthang of ritual music and folk music. The people I met there directed me to Tashi Tsering, the last of the royal court singers who knew a repertoire of gar-glu, court songs that had been passed down from father to son for some hundreds of years, and had no heirs to learn his music. The lyrics were about the Mustangi people’s origin; festivals; weddings; horse races; and what the king and queen of Lo Manthang would wear. So they’re very much about the culture. That summer I recorded seven songs that Tashi Tsering sang for me. Then I notated them and also incorporated fragments of the melodies and other sounds that I heard.

After that trip, Maureen and I wrote Lung-Ta, or The Wind Horse. The piece incorporated a prayer for peace that one of the senior monks, Amchi Tenzin Sangbo Bista, wrote for us on September 11th, 2008. This work was presented as a gift to His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 2009.

After that first trip, you returned to do more field recordings?

Yes. I was really engaged with the idea of recording these songs to help teach the story of the people in upper Mustang and sustain the Mustangi dialect of Tibetan. The people in that region are ethnically Tibetan because that area was part of Tibet before the borders changed in the 18th century.

With help from the Rubin Foundation and some other sources, I was able to return in 2010 with ethnomusicologist Katey Blumenthal, and we completed the recordings of Tashi Tsering’s repertoire as well as recordings of other people in the village who wanted to sing for us. The project grew to include not only the gar-glu court song repertoire but the tro-glu, or common dance songs. Altogether we recorded more than 120 songs.

And then, I began a new body of work that was inspired by these experiences. One of my pieces entitled Tse Go La, Tibetan for “at the threshold of this life,” incorporates some of these melodies so that the singers in the choir could learn about the Mustangi dialect of Tibetan and Tibetan culture, which are somewhat endangered because things are changing so quickly close to the border.

While it has quiet moments, Mila: Great Sorcerer is not a minimalist opera. It features complex instrumentation and many layers that at times can be overwhelming. Is that part of your own personal tastes as a composer or was this aesthetic a result of Tibetan influences?

There’s a complexity in the music that begins to become more spacious in the second act. Sometimes, such as when demons visit Milarepa, the orchestration under the voices is, as you said, complex or dense. That can then be juxtaposed with the spaciousness that comes later in the opera. There’s silence that grows as Mila begins to embody Marpa’s teachings. And so, each time they sing “Listen to the stillness all around,” there are some quiet moments to help the audience enter that place of stillness.

As for Tibetan influences, I was trying to create a new world of sounds, which was not Eastern or Western, in response to this story. I listened, I read, I sat, and I listened more, and the colors that came out were what I thought were needed to convey this story and the underlying psychology. Over the ten years I’ve worked with the Tibetan melodies, they have become a little more internalized. As a result, this opera is more of a synthesis and has less of a Tibetan sound than some of my earlier pieces.

What are some of the characteristics of Tibetan music that you did draw upon?

The folk music and the religious music are different. The sounds that I heard from the folk music were beautiful melodies that had repetition; they are strophic [all verses are sung to the same music]. They tell a story, and the melodies were simple in some ways. For instance, when Tashi Tsering would sing, he would accompany himself with only two drums. The beauty and lyricism of the melody were what was most striking.

You can hear that type of melody in the opera, like when Mila is a young boy and he sings “Dear, dear Mama, gold and turquoise in my hand.”

The ritual music appears in the opera when you hear the clashing of the cymbals and the drums in a progressive accelerando [accelerating tempo]. There were also punctuations with the drum and the cymbal that you might hear in cham dances. And the dunkar, conch shells, would play as an invitation to a ritual. I also used two dungchen long horns, damaru drums, and kangling [Tibetan trumpets] that I brought back from Nepal.

Pardon this, but a few of the horns sounded like farts to me, especially in one scene where demons were mocking Milarepa. Was that meant to be humorous?

Yes, indeed. And certainly there is a moment where flatulence becomes a part of a demon’s mocking aria.

I heard a smattering of laughter among the audience, but I think people don’t always feel comfortable laughing around Buddhist subjects because there’s a lot of reverence, even though the source material is often meant to be funny.

Yes, and Milarepa himself has a great sense of humor. In his stories, you read about some of the things that he says and does. There’s a wonderful sense of humor and a lightness of being. So much of the story is dark—he is manipulated to commit the most atrocious of crimes—and we needed the humor as well.

You have discussed the Tibetan influences—what were some of the Western classical influences that came into this? There’s a tradition of drawing inspiration from folk and mythology, like in Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Did that play a role?

Yes. Wagner used many leitmotifs, which means leading motive, that would relate to a person or a place. Even if that person isn’t present, you can feel them lingering because their leitmotif would appear. Or leitmotifs can combine to show that two parts of the story are coming together.

In this opera, there are many leitmotifs as well. Mila’s theme is just two notes in the opening, and then it very slowly builds to his melody. We hear it in its entirety and then also in fragments, and sometimes it becomes distorted depending on what’s happening in the action. There are leitmotifs for Mila’s breakdown; for the wheel [of birth and death], for work and unfair labor, and the grinding barley; for Milarepa’s innocence; for Mila’s heart and his struggle; for compassion; and so on.

The liner notes make a point to say that this is not a Tibetan production and that it was not meant to be representative of Tibetan music but an interpretation. There is a history of Western music borrowing from folk traditions and either turning the music into a caricature or appropriating the culture. Is this what the liner note was speaking to?

That’s a very important question. We approached this with the utmost respect for the Tibetan culture and an understanding that we are not a Tibetan company. We wanted people to know that we came from a place of humility and honoring the Tibetan tradition and Milarepa as the greatest of the Tibetan Buddhist saints and teachers.

Personally, I wanted to make sure that things were done properly, and that we learned the Tibetan chants with the correct pronunciation. I asked my friend Ven. Lama Losang Samten—who was the former personal assistant to His Holiness and has a sangha in Philadelphia, the Chenrezig Tibetan Center—to come to my studio and record the chants so that the choir could learn the pronunciation.

At the same time, we wanted to make it known that this is a creative interpretation, and we wanted to allow the opera to depict this story of ultimate transformation in its own way. Milarepa’s teachings—that there is a way out of suffering and that our souls can be redeemed—is such an important message. I hope the opera, by bringing that lesson into a different context, makes it available to people who might not have heard about Milarepa.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.