Caits Meissner is a multidisciplinary poet and educator working in New York City’s prisons, schools, and universities, where she facilitates writing workshops that seek to bring connection and dignity to her students. Influenced by Buddhism’s emphasis on compassionate action, Caits is devoted to using the arts as a skillful method of transforming lives. She was also a Tricycle poet-in-residence during National Poetry Month earlier this year. Her new book, Let It Die Hungry, released in October from The Operating System Press, articulates the hungers of the body and spirit through an interwoven set of poems, drawings, and writing prompts that bring the reader into a multifaceted conversation with the writing and one’s self.

Tricycle recently spoke with Meissner to discuss the mutability of identity, the egolessness of friendship, and how to reclaim and develop a kinder relationship to your life story.

Your book has an inherent sense of dana [generosity] in its structure. The writing prompts throughout the text ask readers to reflect on their own experience and there are illustrations throughout—it’s a very non-traditional read.

Generous is a really wonderful word to be reflected back to me. The truth is that I wanted a traditional book of poems: my ego was caught up in wanting that pristine, beautiful collection of poetry. But I was publishing with The Operating System, and I know the editor there. She said to me, “I love your book, but I know you. I know you do drawings, I know you teach. How could you leave those identities out?” Once I started working on it, I was really proud to be bringing my full self into the work.

The writing prompts are culled from lesson plans that I taught at a women’s prison. The class that semester focused on dichotomies. We were looking at the gray area between two polar opposites. The book opens with a discussion of good and evil, rigid versus mutable, silence versus noise. This particular semester was so powerful because there was so much room for the students to find their own entry points into these questions. When my editor suggested including them, it made sense to me. It invites the reader into a conversation with the book and with themselves.

One of the dichotomies you explore in a number of poems, rigid and mutable selves, reminded me of the Buddhist concept of no-self. It appears, for example, in “Ways to Fight for Life in Harlem.” In its final, devastating lines, you take on the voice of another:

Now it’s thin winter. The young ghosts barrel past

the window, coaxing a fight into the streets.

The projects and the Hill are at war, always been.

See, everyone’s dying out here on 125th. Ain’t just me.

We all got seeds in our bellies.

Just some be metal and some be flesh.

Yes this is the voice of another person in this poem, but not the words themselves. That’s what we’re doing in writing: we’re reinventing. This poem is based on a true story. I was working with a young person who had a serious illness whom I became very close to. I would go to her house in Harlem every week for writing dates. Through writing, we would ask ourselves: What might feel good right now? I was trying to support somebody I cared about, but I didn’t have any resources. Instead, I provided a space. I’d bring writing prompts, and we would write together. Those lines come from a moment we had walking to the train when we saw two groups of young people fighting. It was a really intense moment, and she said, “Look, everybody is out here dying in one way or another.” So the poem has layers and levels that talk about surviving illness, but also the impact of America’s deep-seated racism. This is what I’m writing about in the book, the ways we think about surviving in the world: terminal illness, violence, and poverty. This poem is a tribute to this person and the strength of her spirit to survive.

This poem’s examination of survival comes through in “Praise Poem” as well, which is dedicated to the poets at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility.

Yes. That poem was originally published in Amazon’s Day One journal. The editor, Morgan Parker, spoke about the relentless “we” in that poem. Those are her words. This poem is about seeing yourself in connection with people over shared histories and what you have in common. Despite the “relentless we,” there are boundaries around the experience of others I can’t claim, and I have to be careful to recognize that line.

Praise Poem

For the Poets at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility

The circle’s purpose is to see each other

our unspoken rule: commit to looking.

We were born and we will die, everything

in between is filler, debatable, for example

we have hated a woman for snatching

our man away like morning eggs.

We stay awake at night counting

constellations of guilt.

We both feel menstrual today

don’t talk to us.

We call our mothers for comfort

and if they answer, tenuously

measure the distance between truth

and the length of rain.

We read books to remember stories

not of our own making or mess

and thank god, they are good

and thank God they are tragic.

Tragically, we both wonder if we deserve

anything good at all, to feel beautiful

or enjoy the pleasure of another body

when we’ve screwed or screwed up

we dream of undisturbed sand

covering each track and vanishing.

But in this room we crawl through

the window inside, dig up from burial

the dusty banjo of memory, we play

on childhood’s climbing tree,

branches shedding crab apples

snatched up by the deer.

We can praise the fawn for cleaning

the lawn with her hunger.

We can name her tracks in fresh mud,

we can call her kin, coo the name

we’ve crowned her when she shows

her face in the damp morning grass.

And though some of us didn’t have

backyards or a steady bed or a tree to love

we can write a porch into the scene

or a birdhouse or untie a hurt until

it stretches its arms out wide as the sea.

We can invent this common history,

waking up what is untouched and tender,

lit deep inside our bodies’ vast night.

We can remember, it has been proven

that we are made of stars, always vibrating,

sparking, even if it cannot be seen by

the foolish eye and each era, there we are,

unmistakably, a presence growing larger.

Yes, we are spinning: the entire revolving sky.

You write about the “commitment to looking” in that poem. It stands out to me because its something you must do without crumbling. It’s like what you write in the final lines of “Homegirl Manifesto”: Still want to love / this world without dying / or playing dead.

This one is about women—it’s an anthem or manifesto, inspired by Kathleen Hanna (former lead singer of feminist punk band Bikini Kill) and Riot grrrl (an underground feminist hardcore punk movement) about all of the ways women are badass. It’s fun and playful, but that last line sneaks up, I think, because it’s the idea that any identity we hold can be simultaneously something to wear with pride and beauty but also something that can be a barrier, an oppressed identity. For women, “dying or playing dead” is both survival and not-survival. I think this translates across a number of people’s experiences. What transcends the identity of “woman” in that line is the idea that we all want to love where we live. We have a desire and an impulse to be happy. This is what we talk about all the time in life—how can I be happy? This is what this poem is talking about, this desire to be in connection with and to love this world, to love people. But the world is a very broken place that is not a safe for most humans, if any. So how do we negotiate that? How do we still love? How do we hang on to that want to love?

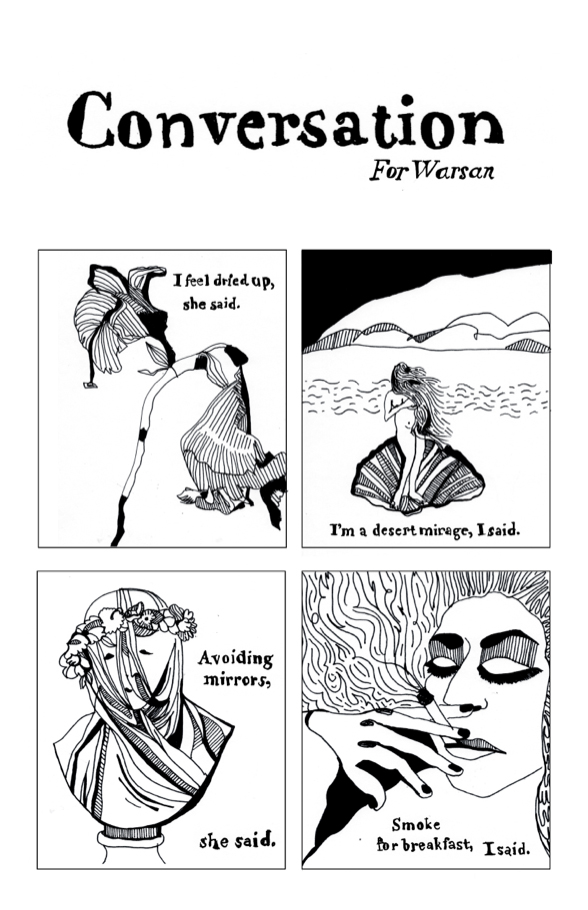

In “Conversation,” the visual poem dedicated to the London-based Somali writer and poet Warsan Shire, it seems that you’re saying something similar about wanting to love this world despite the horror and the heartbreak of it. The poem has a back-and-forth that reminds me of a koan called “True Friends”:

A long time ago in China there were two friends, one who played the harp skillfully and one who listened skillfully. When the one played or sang about a mountain the other would say: “I can see the mountain before us.” When the one played about water, the listener would exclaim: “Here is the running stream!” But the listener fell sick and died. The first friend cut the strings of his harp and never played again. Since that time the cutting of harp strings has always been a sign of intimate friendship.

[From Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings, compiled by Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki]

I love this because I don’t think friendship gets a lot of attention in our spiritual traditions.

Yes, you nailed it. This poem is 100 percent about friendship. “Conversation” is one of my favorite pieces in the book; it’s one of those poems that came out and stayed exactly as it is, which is very rare. I recently did a reading series for women, and I decided to dedicate my entire 20-minute reading to the friendship of women. I actually had to cut some out because there’s so much dedicated to women and friendship in here that I didn’t even realize!

I think that you’re right in saying that friendship doesn’t always get the spotlight. We put a lot of emphasis on family and romantic relationships. I think where friendship is really celebrated is in the queer community, where people take on chosen families because they have sometimes been exiled from their birth families. So there are spaces where friendship is elevated. In my own life, I’ve not really had best friends for the length of my life; there’s been some transience. This brings up some deep sadness sometimes. But, in terms of having the strength to continue writing, it makes me brave.

We should be talking about friendship more, how we become vulnerable in friendship, and what that looks like. I also think there’s a particular depth of friendship between women if women allow for it. We tend to let ourselves be our true selves in front of our closest women friends. We share intimate details of our lives. In a way we become almost romantic. We write each other love letters and we call each other by pet names and we say “I love you” excessively at times. There’s a real romance to friendships between women that I find very nourishing.

There can be an egolessness in this kind of friendship: you’re not worried about being judged, and you think of yourself primarily in terms of your bond to these other people. You’re not constricted into an ego-self.

Yes. Quite frankly it can be transcendent sometimes, a depth of connection like that. You really have to trust somebody to be able to open up. You have to honor that. If that trust is broken, it’s tragic.

Notes on Instinct

— A documentary came out in 2014 that exposed the plight of orca whales. Their sheer mass a form of hypnosis, disbelief that such a body could exist on the same planet as our own. With a hypothesis of a higher emotional capacity than humans, who could blame the beast for dragging a trainer through the water? The friend who fed fish for tricks, who created a sideshow.

— Can one both love this beautiful breathing thing and also be an accomplice to captivity? Is it better to fight for the whale from outside the arena, or pet its wet skin from within the tank?

— When Ming the tiger was kept in the home of Antoine Yeats in New York City housing projects, his owner became a brief celebrity on television. He was quoted urging his peers to pursue PhD’s, to see themselves on the quote/unquote next level of working with animals as an answer to his own misguided propensity for exotic pets.

— Alligator in the bathtub, albino monkeys under sink, elephants in the creek, Lambert the lion escaping through suburban traffic (that last one true down to name.)

— Saw on the news that Cecil the lion was killed by a Midwestern dentist in Zimbabwe. I imagine Cecil rising from the dead under that fluorescent pink sun, a ring of roses strung through his mane, puttying up the potholes, redistributing land, restoring economics, wiping away blood with his sandpaper tongue. Cecil pumped up with laughing gas, cracking up his own name.

— I won’t lie, it is easier, lazy even, to assign purity to a species that does not bear our particular flaws—alive by instinct, lacking ability to craft a gun from wood and metal or cook food above a constructed flame. When I look across my country I have to fight the urge to hate all of us equally. I reach deep inside to what is untouched in me in search of compassion for the form in which I arrived.

— But who will ever know. The lion does not choose its human name. The whale cannot speak to claim self defense. Ming’s claws become enormous when a man’s hand holds on.

In “Notes on Instinct,” you stretch a sense of connection toward consideration of the natural world. You write about the ways that humans have dominated nature and how we are accomplices to captivity.

“Notes on Instinct” is about our desire to consider the world beyond our own species. There’s a piece in it where I’m talking about how I have to reach deep within me to not hate everybody who looks like me in the world: other human beings. When I write, “The lion doesn’t choose his human name,” this is about how we personify and ascribe human qualities to animals.

This particular piece talks about how this lion was killed by a dentist. The lion was named Cecil, which is bizarre because if you know anything about Zimbabwean history—I know some because my husband is Zimbabwean—you’ll know that before colonialism was overthrown in the country it was called Rhodesia. The country was “founded,” by which I mean conquered and colonized, by Cecil Rhodes. I thought this was extremely bizarre that the lion ended up with this name. And here we are with a Midwestern, white American dentist who kills this animal in a country that is not his own. There is a parallel here between colonization and what we do in nature.

I was also thinking about captivity and incarceration. The tiger being kept in a home in this poem is subjected to exotificiation, which is also something that we do to each other as humans. In this case, these species literally don’t have a voice. Humans have placed themselves at the top of the hierarchy and called it the natural order of the universe.

In the midst of this poem that is reflecting on animal life, you write about fighting the urge to hate all of your countrymen equally.

In those lines I’m also talking about needing to reach deep within me to find compassion for humans because I can find humans to be so disgusting at times. It’s easy to have compassion and reverence for the natural world and animals. But how can I care about this body that I come in, the form that I’ve been presented in on this planet? I could hate all of us equally, but instead I have to go within me to find compassion for the perpetrator of these crimes against the universe. Again, it can all be read as a metaphor for working in prisons. I’m connecting it to my emotional landscape, but it becomes a wider lens.

In one of the book’s prompts you ask the reader to compile notes and to create a poem that destroys the ego and rebuilds a kinder, more open orientation to the life and its story. Do you think about this when you’re writing or working with people?

I do when I’m working with people. I don’t think about it much when I’m writing. I do a lot of socio-emotional based facilitation through writing because it’s where my expertise lies, but it’s a fine line because I’m not a mental health worker. I want to say that out loud because I think it can be dangerous to step into those roles without deep training. But this prompt is about framing your own story; it was originally used in prison. You have to think about the stories people are carrying there—they have to forgive themselves if they want to move on in their lives. Often people have done things that they feel deeply guilty about. How do you move beyond beating yourself up and move into a space where you can live within your story without punishing yourself eternally? You must ask: how can I be a contribution to the world again? Guilt and self-punishment become very selfish orientations because they cause you to hide. You separate from other people rather than coming into connection with them. It’s natural, and I’m not blaming, and this is a part of the process of healing, but it’s very difficult. You must take responsibility, hold yourself accountable, and then develop a new relationship to your story. You can be a victim of circumstance, but by rewriting the narrative you gain a different relationship to the way you tell your story. You can learn to live with it, whether you’re the perpetrator, the victim, or both.

Poems and images reprinted with permission from The Operating System

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.